This Week in Freethought History (March 3-9)

Here’s your Week in Freethought History: This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

Last Sunday, March 3, but in 1959, American radio host Ira Glass was born. Glass began working in public radio as an intern in 1978 when he was 19. He moved to Chicago in 1989, where in 1995, the show for which Glass is known as producer and host, “This American Life,” made its debut on WBEZ. The next year, the show went national on Public Radio International (PRI). Each week, “This American Life” takes a theme and looks at it from several different human interest angles. Under Glass’s editorial direction, “This American Life” has won such honors for broadcasting and journalistic excellence as the Peabody and DuPont-Columbia awards and the Robert F. Kennedy Award. He had help from contributors such as Sarah Vowell, an Atheist – but not from God. Indeed, Glass abandoned his belief in God as a teen, but says, “To this day, I feel very Jewish — I couldn’t be anything but a Jew. But when I go to services, it’s not clear why I should be there.” In a 14 December 2000 interview with Chicago Tribune staff writer Robert K. Elder, Glass was candid about his atheism: “I just find I don’t believe in God. It just doesn’t seem to be true, and no amount of thinking about it seems to make it true. It seems inherently untrue... I could pretend I believe a God exists, but the world seems explainable to me without it.”

Last Sunday, March 3, but in 1959, American radio host Ira Glass was born. Glass began working in public radio as an intern in 1978 when he was 19. He moved to Chicago in 1989, where in 1995, the show for which Glass is known as producer and host, “This American Life,” made its debut on WBEZ. The next year, the show went national on Public Radio International (PRI). Each week, “This American Life” takes a theme and looks at it from several different human interest angles. Under Glass’s editorial direction, “This American Life” has won such honors for broadcasting and journalistic excellence as the Peabody and DuPont-Columbia awards and the Robert F. Kennedy Award. He had help from contributors such as Sarah Vowell, an Atheist – but not from God. Indeed, Glass abandoned his belief in God as a teen, but says, “To this day, I feel very Jewish — I couldn’t be anything but a Jew. But when I go to services, it’s not clear why I should be there.” In a 14 December 2000 interview with Chicago Tribune staff writer Robert K. Elder, Glass was candid about his atheism: “I just find I don’t believe in God. It just doesn’t seem to be true, and no amount of thinking about it seems to make it true. It seems inherently untrue... I could pretend I believe a God exists, but the world seems explainable to me without it.”

Last Monday, March 4, but in 1955, American magician and author Penn Jillette was born. In 1975 he found his partner, Teller (Raymond Joseph Teller), and their self-described Penn & Teller “arranged marriage” has them performing regularly “an edgy mix of comedy and magic” and appearing on the Showtime cable series “Penn & Teller: Bullshit!” exposing frauds and fakes such as talking to the dead, alternative medicine, creationism, alien abductions and ESP. Both Penn and Teller are outspoken Atheists and skeptics. In a 1999 interview for The Onion, Penn wryly remarked: “being pro-science is one of the oddest things you can do in show business. … Oh, Western medicine doesn’t work; I’m sorry, we cured polio. What more do you want? Your herbalism has done jack; we cured polio. And guess what? It cures polio even if you don’t believe in it.” “I am an atheist, a very strong atheist,” says Penn. Speaking with Reason magazine, Penn remarked, “People who know about Penn & Teller know that I’m an atheist... People have to realize that having an imaginary friend may be dangerous. When 9/11 hit, the second thing I said to myself was, ‘This really is what religious people do.’ Those people flying the plane were very good, very pious, truly faithful believers.” On faith and Jesus, in a 2004 interview, Penn said, “I will promise you that when evidence comes in differently I’m the first one to change. If you show me evidence of a God, I’m not an atheist. Atheism only means that I don’t believe in God. I don’t believe a God is impossible, I just don’t think there is evidence of one.”

Last Monday, March 4, but in 1955, American magician and author Penn Jillette was born. In 1975 he found his partner, Teller (Raymond Joseph Teller), and their self-described Penn & Teller “arranged marriage” has them performing regularly “an edgy mix of comedy and magic” and appearing on the Showtime cable series “Penn & Teller: Bullshit!” exposing frauds and fakes such as talking to the dead, alternative medicine, creationism, alien abductions and ESP. Both Penn and Teller are outspoken Atheists and skeptics. In a 1999 interview for The Onion, Penn wryly remarked: “being pro-science is one of the oddest things you can do in show business. … Oh, Western medicine doesn’t work; I’m sorry, we cured polio. What more do you want? Your herbalism has done jack; we cured polio. And guess what? It cures polio even if you don’t believe in it.” “I am an atheist, a very strong atheist,” says Penn. Speaking with Reason magazine, Penn remarked, “People who know about Penn & Teller know that I’m an atheist... People have to realize that having an imaginary friend may be dangerous. When 9/11 hit, the second thing I said to myself was, ‘This really is what religious people do.’ Those people flying the plane were very good, very pious, truly faithful believers.” On faith and Jesus, in a 2004 interview, Penn said, “I will promise you that when evidence comes in differently I’m the first one to change. If you show me evidence of a God, I’m not an atheist. Atheism only means that I don’t believe in God. I don’t believe a God is impossible, I just don’t think there is evidence of one.”

Last Tuesday, March 5, but in 1431, God’s agents elected the head of the Roman Catholic Church known as Pope Eugene IV. It is important to remember that 1431, during the Hundred Years War, is the same year in which 19-year-old Joan of Arc was tried and executed by burning. The issue of a liaison between his real father, later Pope Gregory XII (1406-1417), and his aunt, the future pope was pulled from his Augustinian monastery at age 24 and made Bishop of Siena. But as the rulers of the kingdom objected to a bishop who had never been a priest, “uncle” Angelo (Gregory) instead installed him as Cardinal-Priest of St. Clement. As Cardinal, he fathered several children, including at least one, who would later become Pope Paul II (Pietro Barbo), through an incestuous relationship with his own sister. The Catholic Encyclopedia will claim, of course, that popes are infallible, not impeccable. But this desperate apologetic gymnastic deflates any claim of moral superiority for the Roman Catholic Church, for how could the Holy Spirit not look after his own? At about age 43, the newly elected Pope Eugene IV tried to de-authorize the Council of Basle, but was forced into a compromise: the people of Colonna had set up a nominal Republic in Rome and Eugene, fearing for his life, was forced to escape Rome in disguise. But by October 1434, Eugene returned to Rome with a vengeance and, spilling oceans of blood, thousands of men, women and children were slaughtered, tortured and burned on Eugene’s orders. This brutality so horrified Rome that once again Eugene was expelled (1436). He stayed in Colonna for the next seven years, creating a court full of prostitutes and villains for his entertainment. He was replaced by the completely incompetent antipope Pope Felix V, but power slowly returned to Eugene by 1442. He remained pope until his death in 1447.

Last Tuesday, March 5, but in 1431, God’s agents elected the head of the Roman Catholic Church known as Pope Eugene IV. It is important to remember that 1431, during the Hundred Years War, is the same year in which 19-year-old Joan of Arc was tried and executed by burning. The issue of a liaison between his real father, later Pope Gregory XII (1406-1417), and his aunt, the future pope was pulled from his Augustinian monastery at age 24 and made Bishop of Siena. But as the rulers of the kingdom objected to a bishop who had never been a priest, “uncle” Angelo (Gregory) instead installed him as Cardinal-Priest of St. Clement. As Cardinal, he fathered several children, including at least one, who would later become Pope Paul II (Pietro Barbo), through an incestuous relationship with his own sister. The Catholic Encyclopedia will claim, of course, that popes are infallible, not impeccable. But this desperate apologetic gymnastic deflates any claim of moral superiority for the Roman Catholic Church, for how could the Holy Spirit not look after his own? At about age 43, the newly elected Pope Eugene IV tried to de-authorize the Council of Basle, but was forced into a compromise: the people of Colonna had set up a nominal Republic in Rome and Eugene, fearing for his life, was forced to escape Rome in disguise. But by October 1434, Eugene returned to Rome with a vengeance and, spilling oceans of blood, thousands of men, women and children were slaughtered, tortured and burned on Eugene’s orders. This brutality so horrified Rome that once again Eugene was expelled (1436). He stayed in Colonna for the next seven years, creating a court full of prostitutes and villains for his entertainment. He was replaced by the completely incompetent antipope Pope Felix V, but power slowly returned to Eugene by 1442. He remained pope until his death in 1447.

It should be added that Catholic apologists make much of Eugene’s 1435 Papal Bull, Sicut Dudum, in which he supposedly condemned slavery, but in fact Eugene condemned taking Christians as slaves, but non-Christians, and those who refuse to become Christians, are lawfully enslaved. Indeed, this 15th century representative of God on earth was also one of the most superstitious men of his age. A.D. White points out with impeccable authority in his Warfare of Science with Theology, that Eugene, “… by virtue of the teaching power conferred on him by the Almighty, and under the divine guarantee against any possible error in the exercise of it, issued a bull exhorting the inquisitors of heresy and witchcraft to use greater diligence against the human agents of the Prince of Darkness, and especially against those who have the power to produce bad weather. In 1445 Pope Eugene returned again to the charge, and again issued instructions and commands infallibly committing the Church to the doctrine.” Was Eugene just an exemplar of the superstition and brutality of the age, which for some inscrutable reason God allowed (until Freethinkers showed a better way)? It has always been an apologist’s tactic to claim, in so many words, that God was reticent to upset the prevailing morality. We are presumably talking about the same God whose people are unmatched in brutality and superstition, and whose recorded murders of men women and children in the Old Testament were subtle as a brick!

It should be added that Catholic apologists make much of Eugene’s 1435 Papal Bull, Sicut Dudum, in which he supposedly condemned slavery, but in fact Eugene condemned taking Christians as slaves, but non-Christians, and those who refuse to become Christians, are lawfully enslaved. Indeed, this 15th century representative of God on earth was also one of the most superstitious men of his age. A.D. White points out with impeccable authority in his Warfare of Science with Theology, that Eugene, “… by virtue of the teaching power conferred on him by the Almighty, and under the divine guarantee against any possible error in the exercise of it, issued a bull exhorting the inquisitors of heresy and witchcraft to use greater diligence against the human agents of the Prince of Darkness, and especially against those who have the power to produce bad weather. In 1445 Pope Eugene returned again to the charge, and again issued instructions and commands infallibly committing the Church to the doctrine.” Was Eugene just an exemplar of the superstition and brutality of the age, which for some inscrutable reason God allowed (until Freethinkers showed a better way)? It has always been an apologist’s tactic to claim, in so many words, that God was reticent to upset the prevailing morality. We are presumably talking about the same God whose people are unmatched in brutality and superstition, and whose recorded murders of men women and children in the Old Testament were subtle as a brick!

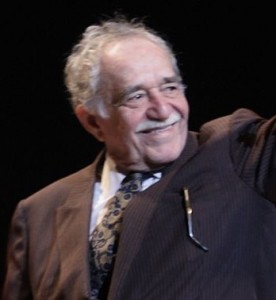

Last Wednesday, March 6, but in 1927, that Latin-American journalist, novelist and short story writer Gabriel García Márquez was born. It was from stories his grandparents told him that Márquez learned to revere Venezuelan military and political leader Simón Bolivar and the revolutionary spirit he embodied. As a journalist, he secretly associated with communists and, in the mid-1950s, while at the Prensa Latina office in Havana, he befriended Fidel Castro. He is chiefly known for his novels (One Hundred Years of Solitude, 1967; Love in the Time of Cholera, 1985), his non-fiction (The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor, 1970) and his short stories. Although brought up culturally as a Roman Catholic, Márquez once said, “If God hadn’t rested on Sunday, He would have had time to finish the world.” And it is clear that he does not take the Bible literally: “Fiction was invented,” said Márquez, “the day Jonas arrived home and told his wife that he was three days late because he had been swallowed by a whale.” The 1982 Nobel Laureate popularized a literary style known as “magical realism” (el realismo magical). For example, in his short story called “Monologue of Isabel Watching It Rain in Macondo,” Márquez uses his “magical realism” to illustrate how religion tilts the social structure against the lower classes and toward men – women are seen as inferior; the constantly falling rain is a metaphor for the religion that weighs down and almost drowns the entire society. In “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings,” Marquez attacks religion by poking fun at the Christian practice of paying collections to the church and acting pious in exchange for answered prayers. Then, once the prayer is answered, the human subjects revert to greed and selfishness. It was Gabriel Garcia Márquez who said, more out of Roman Catholic habit than conviction, “I don’t believe in God, but I’m afraid of Him.”

Last Wednesday, March 6, but in 1927, that Latin-American journalist, novelist and short story writer Gabriel García Márquez was born. It was from stories his grandparents told him that Márquez learned to revere Venezuelan military and political leader Simón Bolivar and the revolutionary spirit he embodied. As a journalist, he secretly associated with communists and, in the mid-1950s, while at the Prensa Latina office in Havana, he befriended Fidel Castro. He is chiefly known for his novels (One Hundred Years of Solitude, 1967; Love in the Time of Cholera, 1985), his non-fiction (The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor, 1970) and his short stories. Although brought up culturally as a Roman Catholic, Márquez once said, “If God hadn’t rested on Sunday, He would have had time to finish the world.” And it is clear that he does not take the Bible literally: “Fiction was invented,” said Márquez, “the day Jonas arrived home and told his wife that he was three days late because he had been swallowed by a whale.” The 1982 Nobel Laureate popularized a literary style known as “magical realism” (el realismo magical). For example, in his short story called “Monologue of Isabel Watching It Rain in Macondo,” Márquez uses his “magical realism” to illustrate how religion tilts the social structure against the lower classes and toward men – women are seen as inferior; the constantly falling rain is a metaphor for the religion that weighs down and almost drowns the entire society. In “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings,” Marquez attacks religion by poking fun at the Christian practice of paying collections to the church and acting pious in exchange for answered prayers. Then, once the prayer is answered, the human subjects revert to greed and selfishness. It was Gabriel Garcia Márquez who said, more out of Roman Catholic habit than conviction, “I don’t believe in God, but I’m afraid of Him.”

Last Thursday, March 7, but in 1727, French economist and contributor to the Encyclopédie André Morellet was born. After a Jesuit education, he kept all his life the title of the Abbé Morellet without religious conviction, for according to the Grande Encyclopédie, he “did more than any in spreading the views of the philosophers.” His writings – including a translation of Beccaria’s Treatise, a smart pamphlet in answer to Charles Palissot’s scurrilous play Les Philosophes (which procured him a short stay in the Bastille), a reply to Ferdinando Galiani’s Commerce des blés, and a French translation of On Crimes and Punishments – were published in 4 vols. in 1818, the year before his death. Because of his able and biting wit, his close friend Voltaire called him “L’Abbé Mords-les” (“Father Bite-them”). Two years after his death, his valuable Memories on the 18th Century and the Revolution were published. Next to Voltaire, Morellet counted among his friends Denis Diderot, Jean le Rond D’Alembert and Benjamin Franklin. Morellet’s semi-satirical translation of Nicolau Eymerich’s Directorium Inquisitorum (written by the 14th century Inquisitor General of Aragon) led to the cessation of some of the French Catholic Church’s more inquisitorial practices.

Last Thursday, March 7, but in 1727, French economist and contributor to the Encyclopédie André Morellet was born. After a Jesuit education, he kept all his life the title of the Abbé Morellet without religious conviction, for according to the Grande Encyclopédie, he “did more than any in spreading the views of the philosophers.” His writings – including a translation of Beccaria’s Treatise, a smart pamphlet in answer to Charles Palissot’s scurrilous play Les Philosophes (which procured him a short stay in the Bastille), a reply to Ferdinando Galiani’s Commerce des blés, and a French translation of On Crimes and Punishments – were published in 4 vols. in 1818, the year before his death. Because of his able and biting wit, his close friend Voltaire called him “L’Abbé Mords-les” (“Father Bite-them”). Two years after his death, his valuable Memories on the 18th Century and the Revolution were published. Next to Voltaire, Morellet counted among his friends Denis Diderot, Jean le Rond D’Alembert and Benjamin Franklin. Morellet’s semi-satirical translation of Nicolau Eymerich’s Directorium Inquisitorum (written by the 14th century Inquisitor General of Aragon) led to the cessation of some of the French Catholic Church’s more inquisitorial practices.

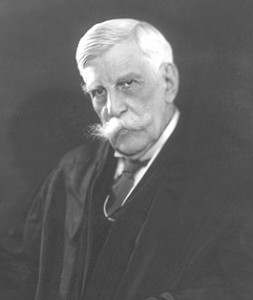

Yesterday, March 8, but in 1841, The Great Dissenter on the US Supreme Court, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was born. His father was the prominent writer and physician Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. (1809-1894) and his mother an abolitionist, during a time when the abolition of slavery was 22 years and a Civil War in the future. The younger Holmes served in the Massachusetts Militia and survived battles at Antietam and Fredericksburg. While at Harvard Law School, Holmes met his future best friend William James, who was studying medicine. In 1902, Holmes was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt to a seat on the United States Supreme Court and unanimously confirmed. He would spend the next 30 years on the Supreme Court with great distinction. His characterization as The Great Dissenter arose from many legal dissents issued on the Supreme Court that nevertheless were incorporated into common law. Holmes believed in free speech and that “the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas – that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.” Throughout most of his legal life, his religious opinion can be said to have been Unitarian. It was Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the eminently quotable writer, who said to a reporter on his 90th birthday, “Young man, the secret of my success is that at an early age I discovered that I was not God.”

Yesterday, March 8, but in 1841, The Great Dissenter on the US Supreme Court, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was born. His father was the prominent writer and physician Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. (1809-1894) and his mother an abolitionist, during a time when the abolition of slavery was 22 years and a Civil War in the future. The younger Holmes served in the Massachusetts Militia and survived battles at Antietam and Fredericksburg. While at Harvard Law School, Holmes met his future best friend William James, who was studying medicine. In 1902, Holmes was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt to a seat on the United States Supreme Court and unanimously confirmed. He would spend the next 30 years on the Supreme Court with great distinction. His characterization as The Great Dissenter arose from many legal dissents issued on the Supreme Court that nevertheless were incorporated into common law. Holmes believed in free speech and that “the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas – that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.” Throughout most of his legal life, his religious opinion can be said to have been Unitarian. It was Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the eminently quotable writer, who said to a reporter on his 90th birthday, “Young man, the secret of my success is that at an early age I discovered that I was not God.”

Today, March 9, but in 1749, French writer, diplomat, journalist and revolutionist Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau was born. Before the French Revolution, Mirabeau was an officer in the army and was several times prosecuted for his courageous criticisms of the feudal system that kept the masses enslaved to the land. During the Revolution he was an influential leader, but a moderate voice who helped to keep the Government on temperate lines. For example, he advocated a reformed monarchy (much like that in England) and a destruction of the power of the Church (unlike that in England). However, during the king’s trial, Mirabeau’s secret dealings with the royal court were publicly revealed, in that he had acted as an intermediary between the monarchy and the revolution and had taken payment for it, so he was largely discredited thereafter. Mirabeau was nearer to Atheism than to the more popular Deism among intellectuals of his day. In 1789, on his death-bed, according to The French Revolution: A History by Thomas Carlyle (1837), Mirabeau pointed to the sun and said, “if that isn't God it is at least his cousin.” Likewise, he rejected the belief in immortality: Mirabeau’s last action before dying, being then unable to speak, was to write one word: “dormir” (to sleep).

Today, March 9, but in 1749, French writer, diplomat, journalist and revolutionist Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau was born. Before the French Revolution, Mirabeau was an officer in the army and was several times prosecuted for his courageous criticisms of the feudal system that kept the masses enslaved to the land. During the Revolution he was an influential leader, but a moderate voice who helped to keep the Government on temperate lines. For example, he advocated a reformed monarchy (much like that in England) and a destruction of the power of the Church (unlike that in England). However, during the king’s trial, Mirabeau’s secret dealings with the royal court were publicly revealed, in that he had acted as an intermediary between the monarchy and the revolution and had taken payment for it, so he was largely discredited thereafter. Mirabeau was nearer to Atheism than to the more popular Deism among intellectuals of his day. In 1789, on his death-bed, according to The French Revolution: A History by Thomas Carlyle (1837), Mirabeau pointed to the sun and said, “if that isn't God it is at least his cousin.” Likewise, he rejected the belief in immortality: Mirabeau’s last action before dying, being then unable to speak, was to write one word: “dormir” (to sleep).

Other birthdays and events this week—

March 6: Italian Renaissance sculptor, painter, and architect Michelangelo was born (1475).

March 7: Greek philosopher and student of Plato, Aristotle (Ἀριστοτέλης, Aristotélēs), died (322 BCE).

March 7: American botanist and horticulturist Luther Burbank was born (1849).

March 9: American writer and editor Michael Kinsley was born (1951).

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in my blog, FreethoughtAlmanac.com.