This Week in Freethought History (September 1-7)

Here’s your week in Freethought History. This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

Last Sunday, September 1, but in 1938, American lawyer and political commentator Alan M. Dershowitz was born. The Clarence Darrow of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Dershowitz made his reputation defending Claus von Bülow in his 1984 attempted murder case, and as part of the “dream team” of defense lawyers that acquitted O.J. Simpson on murder charges in 1995. A patron of many Jewish causes, Dershowitz says, “God is not central to my particular brand of Jewishness. … Being Jewish, to me, transcends theology or deity.” And, “I consider myself a committed Jew, but I do not believe that being a Jew requires belief in the supernatural. … Indeed, it is while praying that I experience my greatest doubts about God, and it is while looking at the stars that I make the leap of faith. … If there is a governing force, He (or She or It) is certainly not in touch with those who purport to be speaking on His behalf.” Last Monday, September 2, but in 1666, the Great Fire of London, which destroyed 4/5 of the medieval city that had just the year before been visited by the Plague, started… on a Sunday. Before the fire burned out, five days later, it had destroyed 13,200 houses, the Royal Exchange, the Custom House and St Paul’s Cathedral. It wasn’t as if London hadn’t been warned, and no psychic powers were necessary. Fires in London were common. Construction of homes and shops was principally wood, thatch and pitch. The heat of a dry summer had depleted London water reserves. All it took was inattentiveness to a baker’s fire believed extinguished the night before.

Last Monday, September 2, but in 1666, the Great Fire of London, which destroyed 4/5 of the medieval city that had just the year before been visited by the Plague, started… on a Sunday. Before the fire burned out, five days later, it had destroyed 13,200 houses, the Royal Exchange, the Custom House and St Paul’s Cathedral. It wasn’t as if London hadn’t been warned, and no psychic powers were necessary. Fires in London were common. Construction of homes and shops was principally wood, thatch and pitch. The heat of a dry summer had depleted London water reserves. All it took was inattentiveness to a baker’s fire believed extinguished the night before.

A Parliamentary committee reported in January 1667 that “nothing hath yet been found to argue it to have been other than the hand of God upon us, a great wind, and the season so very dry.” But was it God’s will that people lived in unsanitary, tightly closed conditions? Was it God’s will that 87 churches and six chapels burned? Did only sinners live in London north of the Thames, and none in Southark, which was spared fire only because London Bridge collapsed? Was it a miracle that, although one sixth of London’s population of 600,000 became homeless, only 16 people perished? And if the fire had been arson, would we gather in groups and sing hymns of praise to the arsonist? Of course not. So why does God get praise for doing something that would land a mere human in jail?

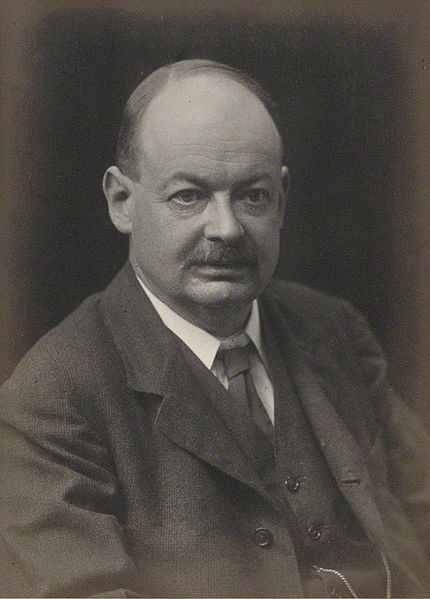

Last Tuesday, September 3, but in 1866, British idealist metaphysician John McTaggart was born. A lecturer on philosophy at Cambridge, in Studies in Hegelian Cosmology he says that the Absolute “is not God, and in consequence there is no God.” In Some Dogmas of Religion McTaggart defines religion as “an emotion that rests on a conviction of harmony between ourselves and the universe at large,” defines God as “a being who is personal, supreme, and good,” yet says we have “no reason to suppose that God exists.” Although a radical in his youth, McTaggart’s political and religious/mystical views developed to be more complex as he matured and are often seen as contradictory. A lifelong atheist, McTaggart opposed materialism and developed a semi-mystical, idealist notion that the world is composed of souls related to one another by love. And in the 1908 work for which he is best known today, The Unreality of Time, McTaggart argues that our perception of time is an illusion, and that time itself is merely an ideal. He seems early on to have rejected the idea of personal immortality, yet later to defend the immortality of souls and the idea of reincarnation. John McTaggart died in London on 18 January 1925 and was buried at Trinity College, Cambridge. The inscription on his tomb, written in Latin, reads, “The free man thinks about nothing less often than death, and his wisdom is the preparation not for death, but for life.” Last Wednesday, September 4, but in 1908, African-American novelist and poet Richard Wright was born. Early on, Wright developed a fascination with books – a love of learning that only deepened his dissatisfaction with life as a black boy in the segregated South. He began to read contemporary American literature and was strongly influenced by H.L. Mencken. Dreaming of a better life in the North, Wright moved to Chicago and, in 1932, as a member of the John Reed Club, an intellectual arm of the Communist party, he found his first encouragement to write – without the rampant racism of the Caucasian culture. His novel, Native Son, completed with a Guggenheim Fellowship, earned him critical acclaim in 1940. In 1944 he broke with the Communist Party, but continued to espouse a liberal ideology and a deep skepticism toward religion. The next year (1945) Wright published his most famous work, Black Boy, an autobiography about his youth in the segregated South. In it, he not only criticizes black culture for not providing a strong foundation for its race, but he also articulates his alienation from organized religion. He became friends with Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus after moving to Paris in 1946. Wright’s novel, The Outsiders (1953), shows how much of their Existentialism he adopted. Wright became a French citizen in 1947 and never saw the US again. Three years before his death, in his 1957 Pagan Spain, based on his travels in the Iberian Peninsula, Wright wrote:Last Thursday, September 5, but in 1793, an 11-month Reign of Terror followed the French Revolution. Sometimes called the Red Terror, to distinguish it from the equally brutal but little-mentioned White Terror (clerical-royalist restoration) which followed it, the Reign of Terror lasted until the execution of Maximilian Robespierre on 28 July 1794. In less than a year, about 18,000 people were killed, an average of 55 a day. The massacres and beheadings were excessive, and supervised by the Committee of Public Safety, in which Georges Danton and Robespierre were influential members. Religious writers, when they speak of the French Revolution at all, are fond of pointing to the Terror as proof that people deprived of their religion turn into beasts with no moral compass.I have no religion in the formal sense of the word. …. I have no race except that which is forced upon me. I have no country except that to which I’m obliged to belong. I have no traditions. I’m free. I have only the future.”

In determining how to think about this history, it is important to keep four points in mind: (1) The Terror was not part of the French Revolution, but took place four years after it. (2) During the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572, more than twice as many people (50,000) were killed over religion in 40 days, as French anti-revolutionaries were killed over politics in the Reign of Terror! (3) The Committee of Public Safety, supported by the people of Paris, was created to preserve the reformed government and to put down threats from inside the country. The clergy, in league with the nobles, were plotting the reversal of the Revolution and clerical-royalist conspiracies were real: the crowned heads of Europe wanted to smother democratic ideas in the cradle. Half of the French Catholic clergy fought for the failure of the Republican government, enlisting the aid of Austrian, English, Prussian and Spanish powers – which in any other regime would be considered treason! (4) The principal author of the Terror, Robespierre, was a Deist believer. So not only were the greatest excesses of the Reign of Terror perpetrated under a man of God, but the reactionary clerical-royalists dipped their hands in blood, as well. France is a secular republic today because, unlike the U.S. and some other nations, France knows what religious strife is really like.

Yesterday, September 6, but in 1809, German Biblical critic Bruno Bauer was born. Bauer studied in Berlin and came under the influence of Georg W. F. Hegel (1770-1831). After publishing his Critical Exhibition of the Religion of the Old Testament, interpreting all biblical miracles in Naturalistic terms, he was transferred to Bonn. Bauer was removed from his chair of theology at Bonn in 1842 for Rationalism and after publishing Critique of the Evangelical History of John in 1840 and Critique of the Evangelical History of the Synoptics in 1841. Bauer himself was never an orthodox Christian. Considered one of the leading German Biblical critics of the 19th century, and claimed by both the left wing and the right wing of the Hegelian school, by the end of his life Bauer was spurned by both parties. The former teacher and friend of Karl Marx, he broke with Marx and Frederick Engels over their socialism and communism, later associating with Max Stirner (1806-1856) and Friedrich Nietzsche. Bauer never married, but he continued to write books to the end of his life, self-publishing and supporting himself through work in his family’s tobacco shop. Justifying his Rationalist approach to biblical scholarship and criticism, it was Bruno Bauer who said (1842), “Reason is the true creative power, for it produces itself as Infinite Self-consciousness, and its ongoing creation is ... world history.” Today, September 7, but in 1533, the first Queen Elizabeth, monarch of the “Golden Age” of English history, was born. Although a disappointment to her father, King Henry VIII, who desperately wanted a son, Elizabeth succeeded to the English throne in 1558 and was well prepared to rule for the next 44 years. Writers on the period, both rationalist and religious, admit that skepticism had spread widely by the dawn of the Elizabethan Age. Indeed, contemporary clerical writers spoke sternly about the rise of atheism. Elizabeth reversed the sober and cautious zeitgeist of earlier years and indulged her appetites for sport (especially riding), music and dancing, pageants and palace parties, and, although not much interested in literature herself, created an atmosphere in which playwrights such as Shakespeare and Marlowe could flourish. Historians cannot claim that she was orthodox in any creed – the Pope excommunicated her in 1570, but she may have seen that as a badge of honor. As one historian put it, “it can hardly be doubted that she was sceptical or indifferent” to religion. Another writes that, compared to others, “no woman ever lived who was so totally destitute of the sentiment of religion.” Elizabeth, like the men around her, was boisterous, vigorous, vulgar, coarse and quite tolerant of the general licentiousness of the age. By the time she died in 1603, Elizabeth I had turned a debtor nation, riven by religion, into one of the most powerful and prosperous countries in the world.Other birthdays and events this week—

September 1: Swiss psychiatrist August Forel was born (1848).

September 3: Gregory I (“the Great”) became pope (590), but how Great was he?.

September 6: American social reformer Jane Addams was born (1860).

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in my blog, FreethoughtAlmanac.com.