This Week in Freethought History (February 24-March 2)

Here’s your Week in Freethought History: This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

Last Sunday, February 24, but in 1852, Irish writer George Moore was born. First intent on becoming a painter, in the 1870s he traveled to Paris and absorbed not only French artistic ideas, but French realist literary ideas, as well, and was especially influenced by Émile Zola. Deciding his artistic talents were not up to contemporary standards, Moore distinguished himself in literature, although his talents even in that field were not universally appreciated at the time. Although not outspoken on religion, his 1911 literary play, The Apostle, and his 1916 novel, The Brooke Kerith, clearly rejected the Christian view of Jesus. Moore speculated (influenced by the ex-Catholic priest, Joseph McCabe, who knew him) that Jesus was probably an Essenian monk up to the age of 30 (one of an ascetic a Jewish religious group that flourished from the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century CE) and that instead of dying on the cross, Jesus was nursed back to health. An agnostic, the Catholic-born Moore preferred to be regarded as a Protestant, even though Protestants, too, were troubled by his ideas about Jesus. He preference was based on his abhorrence of the Roman Catholic Church.

Last Sunday, February 24, but in 1852, Irish writer George Moore was born. First intent on becoming a painter, in the 1870s he traveled to Paris and absorbed not only French artistic ideas, but French realist literary ideas, as well, and was especially influenced by Émile Zola. Deciding his artistic talents were not up to contemporary standards, Moore distinguished himself in literature, although his talents even in that field were not universally appreciated at the time. Although not outspoken on religion, his 1911 literary play, The Apostle, and his 1916 novel, The Brooke Kerith, clearly rejected the Christian view of Jesus. Moore speculated (influenced by the ex-Catholic priest, Joseph McCabe, who knew him) that Jesus was probably an Essenian monk up to the age of 30 (one of an ascetic a Jewish religious group that flourished from the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century CE) and that instead of dying on the cross, Jesus was nursed back to health. An agnostic, the Catholic-born Moore preferred to be regarded as a Protestant, even though Protestants, too, were troubled by his ideas about Jesus. He preference was based on his abhorrence of the Roman Catholic Church.

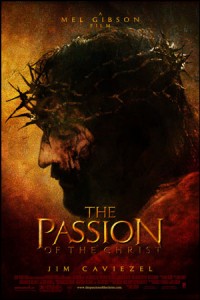

Last Monday, February 25, but in 2004, The Passion of the Christ, a film written and directed by American Mel Gibson, about the arrest, trial, crucifixion and death of Jesus, was released in the United States. The film was given an “R” rating for excruciating violence and thematic content. Although passed over at the Oscars, for its $30 million budget, the film made almost a quarter million dollars on over 950 screens its opening weekend. The Passion of the Christ is the highest-grossing R-rated film in US box office history, earning over $612 million as of February 2013. Not surprisingly, in spite of its violence, blood and gore, Christians rated The Passion of the Christ highly, while mainstream critics were mixed: Slate reviewer David Edelstein called it “a two-hour-and-six-minute snuff movie,” and Jami Bernard of the New York Daily News called it “the most virulently anti-Semitic movie made since the German propaganda films of World War II.” Director Mel Gibson, of Mad Max, Braveheart and Lethal Weapon fame, is a devout Catholic, and his marketing of the film cleverly called his critics the “dupes of Satan” to make negative reviews seem like an attack on Christian religious beliefs instead of on his film’s historical, moral and artistic content.

Last Monday, February 25, but in 2004, The Passion of the Christ, a film written and directed by American Mel Gibson, about the arrest, trial, crucifixion and death of Jesus, was released in the United States. The film was given an “R” rating for excruciating violence and thematic content. Although passed over at the Oscars, for its $30 million budget, the film made almost a quarter million dollars on over 950 screens its opening weekend. The Passion of the Christ is the highest-grossing R-rated film in US box office history, earning over $612 million as of February 2013. Not surprisingly, in spite of its violence, blood and gore, Christians rated The Passion of the Christ highly, while mainstream critics were mixed: Slate reviewer David Edelstein called it “a two-hour-and-six-minute snuff movie,” and Jami Bernard of the New York Daily News called it “the most virulently anti-Semitic movie made since the German propaganda films of World War II.” Director Mel Gibson, of Mad Max, Braveheart and Lethal Weapon fame, is a devout Catholic, and his marketing of the film cleverly called his critics the “dupes of Satan” to make negative reviews seem like an attack on Christian religious beliefs instead of on his film’s historical, moral and artistic content.

In The Passion of the Christ, much of the “passion” – a word which in the original Latin means suffering and pain – is the based on the visions and imaginings of an early 19th century religious fanatic, Anne Catherine Emmerich (1774-1824). Gibson made heavy and uncredited use of her gruesome, sadistic and anti-Semitic detail, which appear to be a fantastic collage of medieval legend, Catholic tradition and pure delusion. The delusion part is most telling: Emmerich filled in the gaps in the Gospels with the ravings of an inedic (one who claims to live without food). The Passion of the Christ is not a documentary, because it leaps way beyond the facts, not a religious drama, because it is over two hours of mostly gratuitous violence, with no greater message than that bad people can hurt you, but in fact is sadomasochism with a nearly homoerotic focus on male flesh. Mel Gibson’s true passion, in the sense of enthusiasm, is anti-Semitism and Roman Catholic fundamentalism.

In The Passion of the Christ, much of the “passion” – a word which in the original Latin means suffering and pain – is the based on the visions and imaginings of an early 19th century religious fanatic, Anne Catherine Emmerich (1774-1824). Gibson made heavy and uncredited use of her gruesome, sadistic and anti-Semitic detail, which appear to be a fantastic collage of medieval legend, Catholic tradition and pure delusion. The delusion part is most telling: Emmerich filled in the gaps in the Gospels with the ravings of an inedic (one who claims to live without food). The Passion of the Christ is not a documentary, because it leaps way beyond the facts, not a religious drama, because it is over two hours of mostly gratuitous violence, with no greater message than that bad people can hurt you, but in fact is sadomasochism with a nearly homoerotic focus on male flesh. Mel Gibson’s true passion, in the sense of enthusiasm, is anti-Semitism and Roman Catholic fundamentalism.

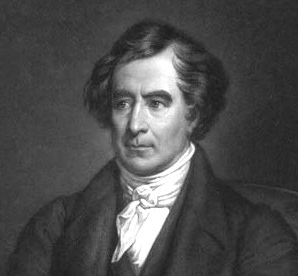

Last Tuesday, February 26, but in 1786, the French mathematician, physicist, astronomer and politician François Arago was born. Brought up before, and maturing during the French Revolution, he became one of the greatest French astronomers and physicists of the nineteenth century. Although tempted by the clerical-royalist reaction after 1814, he joined the anti-clerical side after the Revolution of 1830 as a deputy in the Chambre. During the Revolution of 1848 he fought at the barricades, at the age of 62, and afterward rose to Minister of War and Marine. In these positions he oversaw the abolition of slavery throughout France and its colonies and championed universal male suffrage in France. Academically, Arago was appointed Perpetual Secretary of the French Academy, to which he was admitted at the young age of 23, and was awarded the Copley Medal by the Royal Society for his work in physics and astronomy. An outspoken atheist, there is an abundance of anti-clerical and agnostic opinion in his letters to his friend Alexander von Humboldt (another scientific freethinker). The French Grande Encyclopédie calls Arago “one of the most illustrious savants of the nineteenth century.”

Last Tuesday, February 26, but in 1786, the French mathematician, physicist, astronomer and politician François Arago was born. Brought up before, and maturing during the French Revolution, he became one of the greatest French astronomers and physicists of the nineteenth century. Although tempted by the clerical-royalist reaction after 1814, he joined the anti-clerical side after the Revolution of 1830 as a deputy in the Chambre. During the Revolution of 1848 he fought at the barricades, at the age of 62, and afterward rose to Minister of War and Marine. In these positions he oversaw the abolition of slavery throughout France and its colonies and championed universal male suffrage in France. Academically, Arago was appointed Perpetual Secretary of the French Academy, to which he was admitted at the young age of 23, and was awarded the Copley Medal by the Royal Society for his work in physics and astronomy. An outspoken atheist, there is an abundance of anti-clerical and agnostic opinion in his letters to his friend Alexander von Humboldt (another scientific freethinker). The French Grande Encyclopédie calls Arago “one of the most illustrious savants of the nineteenth century.”

Last Wednesday, February 27, but in 1823, French scholar Ernest Renan was born. Destined for the priesthood, and having taken minor orders, Renan gave up those studies after reading German philosophy and remained a Pantheist throughout his life. As professor of Hebrew, Syriac, and Chaldaic at Paris University, he angered the clergy and lost this position by publishing his Life of Jesus (1863) – which, nevertheless, sold 300,000 copies in France alone and was translated into nearly every European language. In it, Renan wrote: “None of the miracles with which the old histories are filled took place under scientific conditions. Observation, which has never once been falsified, teaches us that miracles never happen but in times and countries in which they are believed, and before persons disposed to believe them. No miracle ever occurred in the presence of men capable of testing its miraculous character.” Although Renan would still refer to “God” and the divinity (in the Romantic sense) of Jesus in his writings, his work helped to enlighten and secularize France by destroying the supernatural idea of Jesus. He won back his chair at Paris University in 1871, due in part to brilliant works on early Christianity, but held his tongue against criticizing religion out of respect for the royalist Weltanschauung. Ernest Renan, who did not believe in a future life, once said, “I know that when I am dead nothing of me will remain.”

Last Wednesday, February 27, but in 1823, French scholar Ernest Renan was born. Destined for the priesthood, and having taken minor orders, Renan gave up those studies after reading German philosophy and remained a Pantheist throughout his life. As professor of Hebrew, Syriac, and Chaldaic at Paris University, he angered the clergy and lost this position by publishing his Life of Jesus (1863) – which, nevertheless, sold 300,000 copies in France alone and was translated into nearly every European language. In it, Renan wrote: “None of the miracles with which the old histories are filled took place under scientific conditions. Observation, which has never once been falsified, teaches us that miracles never happen but in times and countries in which they are believed, and before persons disposed to believe them. No miracle ever occurred in the presence of men capable of testing its miraculous character.” Although Renan would still refer to “God” and the divinity (in the Romantic sense) of Jesus in his writings, his work helped to enlighten and secularize France by destroying the supernatural idea of Jesus. He won back his chair at Paris University in 1871, due in part to brilliant works on early Christianity, but held his tongue against criticizing religion out of respect for the royalist Weltanschauung. Ernest Renan, who did not believe in a future life, once said, “I know that when I am dead nothing of me will remain.”

Last Thursday, February 28, but in 1533, the French creator of the essay form in literature, Michel de Montaigne was born. His mother’s family were conversos, that is, Spanish Jews forcibly converted to Catholicism. Educated in Bordeaux, where Monaigne learned to speak Latin before French, and had a fair knowledge of Greek at the age of six. Two years after his father’s death in 1568, Montaigne resigned the Bordeaux Parlement and retired to the life of a country gentleman at the family château where he completed the first books of his famous Essays (1580-1588), wherein this “literary device for saying almost everything about anything,” as Aldous Huxley called the essay form, benefited not only France, but were quoted by Shakespeare and imitated by Francis Bacon. As the Essays were published, the 1572 St. Bartholomew’s Massacre was a fresh memory in France, so Montaigne professed to be a Catholic. Yet he made some risky statements in his most famous work: “Man is certainly stark mad; he cannot make a flea yet he makes gods by the dozen.” “Men of simple understanding, little inquisitive and little instructed, make good Christians.” “How many things that were articles of faith yesterday are fables today.” “Nothing is so firmly believed as what we least know.” “Everyone’s true worship was that which he found in use in the place where he chanced to be.” “To know much is often the cause of doubting more.” Montaigne was a Deist, although he may have been a secret atheist. Even though his Essays were put on the Catholic Index of Prohibited Books, the Catholic Encyclopedia does not blush to claim him. Montaigne died as he had lived: a Humanist, believing in God, but with a great disdain for the Church.

Last Thursday, February 28, but in 1533, the French creator of the essay form in literature, Michel de Montaigne was born. His mother’s family were conversos, that is, Spanish Jews forcibly converted to Catholicism. Educated in Bordeaux, where Monaigne learned to speak Latin before French, and had a fair knowledge of Greek at the age of six. Two years after his father’s death in 1568, Montaigne resigned the Bordeaux Parlement and retired to the life of a country gentleman at the family château where he completed the first books of his famous Essays (1580-1588), wherein this “literary device for saying almost everything about anything,” as Aldous Huxley called the essay form, benefited not only France, but were quoted by Shakespeare and imitated by Francis Bacon. As the Essays were published, the 1572 St. Bartholomew’s Massacre was a fresh memory in France, so Montaigne professed to be a Catholic. Yet he made some risky statements in his most famous work: “Man is certainly stark mad; he cannot make a flea yet he makes gods by the dozen.” “Men of simple understanding, little inquisitive and little instructed, make good Christians.” “How many things that were articles of faith yesterday are fables today.” “Nothing is so firmly believed as what we least know.” “Everyone’s true worship was that which he found in use in the place where he chanced to be.” “To know much is often the cause of doubting more.” Montaigne was a Deist, although he may have been a secret atheist. Even though his Essays were put on the Catholic Index of Prohibited Books, the Catholic Encyclopedia does not blush to claim him. Montaigne died as he had lived: a Humanist, believing in God, but with a great disdain for the Church.

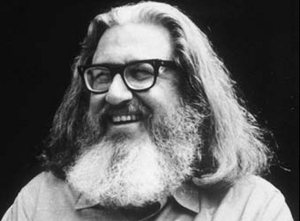

Yesterday, March 1, but in 1922, American publisher and founder of MAD Magazine William M. Gaines was born. Gaines became a comic book publisher literally by accident when, in 1947, his father, the publisher of Educational Comics, died in a freak boating accident. The 25-year-old Gaines inherited EC, which he changed to “Entertaining Comics,” but a book by Dr. Frederic Wertham, Seduction of the Innocent, charged that full-color horror and science-fiction comic books, which happened to be Gaines’s most popular titles, caused juvenile delinquency. A Senate investigation in the mid-1950s resulted in the founding of the Comic Code Authority, so Gaines had to invent the black-and-white, self-deprecating satire magazine: MAD. Along with the self-described “usual gang of idiots,” Gaines made MAD popular with young people from the 1960s through the 1980s (it is still published today). And MAD’s comic skewering did not spare religion. One satire, called “The Academy for the Radical Religious Right Course Catalogue,” included perfect caricatures of Pat Robertson, Phyllis Schlafly, Donald Wildmon, Ralph Reed and other religious bigots of the day, and begins: “Why do members of the radical religious right think the way they do? Are they born like that? Did they have a bad accident as a child? A tragic love affair that soured them on the world? The answer is: none of the above! You have to be taught to be so self-righteous and narrow-minded! It takes years of schooling at a highly specialized learning institution! And we’ve managed to get our grimy little hands on a brochure for such a place.” The jumbo-sized Gaines was still publishing at his death in June 1992. When emphasizing his sincerity, wrote biographer Frank Jacobs, Gaines would declare, “On my honor as an atheist…”

Yesterday, March 1, but in 1922, American publisher and founder of MAD Magazine William M. Gaines was born. Gaines became a comic book publisher literally by accident when, in 1947, his father, the publisher of Educational Comics, died in a freak boating accident. The 25-year-old Gaines inherited EC, which he changed to “Entertaining Comics,” but a book by Dr. Frederic Wertham, Seduction of the Innocent, charged that full-color horror and science-fiction comic books, which happened to be Gaines’s most popular titles, caused juvenile delinquency. A Senate investigation in the mid-1950s resulted in the founding of the Comic Code Authority, so Gaines had to invent the black-and-white, self-deprecating satire magazine: MAD. Along with the self-described “usual gang of idiots,” Gaines made MAD popular with young people from the 1960s through the 1980s (it is still published today). And MAD’s comic skewering did not spare religion. One satire, called “The Academy for the Radical Religious Right Course Catalogue,” included perfect caricatures of Pat Robertson, Phyllis Schlafly, Donald Wildmon, Ralph Reed and other religious bigots of the day, and begins: “Why do members of the radical religious right think the way they do? Are they born like that? Did they have a bad accident as a child? A tragic love affair that soured them on the world? The answer is: none of the above! You have to be taught to be so self-righteous and narrow-minded! It takes years of schooling at a highly specialized learning institution! And we’ve managed to get our grimy little hands on a brochure for such a place.” The jumbo-sized Gaines was still publishing at his death in June 1992. When emphasizing his sincerity, wrote biographer Frank Jacobs, Gaines would declare, “On my honor as an atheist…”

Today, March 2, but in 1810, the man who would become Pope Leo XIII was born. Leo was an aggressive exponent of the religious philosophy of Thomas Aquinas. This perhaps explains why, becoming pope in 1878, chiefly because he was not expected to live long (he was just shy of age 68), Leo had great difficulty reconciling the Church to the modern world. Leo especially objected to things we take for granted today: free elections, secular public education, separation of church and state, legal divorce and equality before the law. Known primarily for two encyclicals, in Humanum Genus Leo defied the modern world by intoning, “It is quite unlawful to demand, defend, or to grant unconditional freedom of thought, or speech, of writing or worship, as if these were so many rights given by nature to man,” and “Divorce is born of perverted morals and leads to vicious habits.” Leo’s other great encyclical, Rerum Novarum, was a tepid endorsement of a living wage for workers, with no specifics, that was repudiated by his successor, Pius XI, who endorsed the Fascist-Corporate State. Leo’s embarrassing admonishment of “Americanism,” in an 1898 letter to Cardinal James Gibbons (“Testem Benevolentiæ”), was also disowned by his successors. In sum, the best that can be said for him, aside from his opening of the Vatican secret archives (they were slammed shut after his death), is that by dividing the world into two camps, one for Catholics and one for everyone else, who followed Satan, Leo showed the true medieval pedigree than drags on the Roman Catholic Church to this day.

Today, March 2, but in 1810, the man who would become Pope Leo XIII was born. Leo was an aggressive exponent of the religious philosophy of Thomas Aquinas. This perhaps explains why, becoming pope in 1878, chiefly because he was not expected to live long (he was just shy of age 68), Leo had great difficulty reconciling the Church to the modern world. Leo especially objected to things we take for granted today: free elections, secular public education, separation of church and state, legal divorce and equality before the law. Known primarily for two encyclicals, in Humanum Genus Leo defied the modern world by intoning, “It is quite unlawful to demand, defend, or to grant unconditional freedom of thought, or speech, of writing or worship, as if these were so many rights given by nature to man,” and “Divorce is born of perverted morals and leads to vicious habits.” Leo’s other great encyclical, Rerum Novarum, was a tepid endorsement of a living wage for workers, with no specifics, that was repudiated by his successor, Pius XI, who endorsed the Fascist-Corporate State. Leo’s embarrassing admonishment of “Americanism,” in an 1898 letter to Cardinal James Gibbons (“Testem Benevolentiæ”), was also disowned by his successors. In sum, the best that can be said for him, aside from his opening of the Vatican secret archives (they were slammed shut after his death), is that by dividing the world into two camps, one for Catholics and one for everyone else, who followed Satan, Leo showed the true medieval pedigree than drags on the Roman Catholic Church to this day.

Other birthdays and events this week—

February 24: Italian poet, composer of the opera Mefistofele and librettist for Giuseppe Verdi, Arrigo Boito was born (1842).

February 26: French Romantic novelist, poet and dramatist Victor Hugo, author of Les Misérables, was born (1802).

February 27: The first American professional poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born (1807).

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in my blog, FreethoughtAlmanac.com.