This Week in Freethought History (November 10-16)

Here’s your week in Freethought History. This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

Last Sunday, November 10, but in 1925, Welsh actor Richard Burton was born. Burton was “discovered” by Hollywood, and made a good impression in The Robe (1953), then became a superstar as King Arthur in the Broadway musical Camelot in 1960 – winning a Tony Award – and as Marc Antony in the 1963 film version of Cleopatra. Burton and his Cleopatra costar Elizabeth Taylor teamed for nuptials (twice) and for more films, such as The Sandpiper (1965), Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) and The Taming of the Shrew (1967). Later Richard Burton films include Anne of the Thousand Days (1969), and Equus (1977), and the title role in the 1983 TV mini-series Wagner. One of his most acclaimed stage performances was as Hamlet, directed by Sir John Gielgud, and his film version of the play Becket – both in 1964. About faith, Richard Burton wrote this in his diary in 1969,

The more I read about man and his maniacal ruthlessness and his murderous envious scatological soul, the more I realize that he will never change. Our stupidity is immortal, nothing will change it. The same mistakes, the same prejudices, the same injustice, the same lusts wheel endlessly around the parade ground of the centuries. Immutable and ineluctable. I wish I could believe in a god of some kind but I simply cannot.

Last Monday, November 11, but in 1922, science fiction and satire writer Kurt Vonnegut Jr was born. A World War Two veteran, Vonnegut is known chiefly for his novels Mother Night (1962), filmed in 1996, Cat’s Cradle (1963), and his 1969 novel Slaughterhouse Five, filmed in 1972, in which he recalled some of his war experience. Slaughterhouse Five elevated Vonnegut to #1 on the New York Times best-seller list. Vonnegut’s other novels include Breakfast of Champions (1979) and Timequake (1997), in addition to essays, short stories, and screenplays. Vonnegut was known for his humanist beliefs and was 1992 Humanist of the Year, honorary president of the American Humanist Association and a lifetime member of the American Civil Liberties Union. In an interview in Free Inquiry magazine, he said, “For at least four generations my family has been proudly skeptical of organized religion.” In his autobiographical book, Palm Sunday, Vonnegut interviews himself, asking how he was affected by his study of anthropology at the University of Chicago. Vonnegut answers, “…it confirmed my atheism, which was the religion of my fathers anyway.”

Last Tuesday, November 12, but in 1815, feminist pioneer Elizabeth Cady Stanton was born. As a girl she flirted briefly with fundamentalism, but her father nipped that in the bud. As Stanton recalled, his instruction “disabused my mind of hell and the devil and of a cruel, avenging God, and I have never believed in them since.” She studied law under her father, who later became a New York Supreme Court judge. During this period she became a strong advocate of women’s rights. Stanton grew to use the term “Nature” interchangeably with “God” in her speeches, observing that “The Bible and the Church have been the greatest stumbling blocks in the way of women’s emancipation.” In collaboration with the more moderate Susan B. Anthony, Stanton wrote a History of Woman Suffrage (1887-1902), which is highly critical of the churches. Of the Bible she wrote, “I know of no other books that so fully teach the subjection and degradation of women.” In an article entitled “What has Christianity Done for Women?” Stanton replied decidedly: Nothing. Late in her life, Stanton wrote, “I can say that the happiest period of my life has been since I emerged from the shadows of superstitions of the old theologies.” And in her 1898 autobiography, Stanton deplored that “the religious superstitions of women perpetuate their bondage.”

Last Wednesday, November 13, but in 1969, Somali-Dutch-American feminist and atheist activist, writer and politician Ayaan Hirsi Ali was born. When Ayann was 5 years old, her grandmother had the girl’s genitals ritually cut off in what is commonly called female genital mutilation or FGM. The family left Somalia, then Kenya, until Ayann finally escaped to the Netherlands. She declared herself an atheist in 2002 and began speaking and writing her critiques of Islam. In 2004, the film Submission, written by Hirsi Ali and directed by Theo van Gogh, was released. This caused a stir in the Dutch Muslim community and elsewhere for its artistic portrayal of the abuse of women by forces of Muslim orthodoxy. The director was stabbed to death in the street by a Dutch Muslim fundamentalist on 2 November 2004. The murderer then affixed to the body with his knife a letter calling for the death of Hirsi Ali. Unafraid, she remained in Parliament another two years and published an autobiography in 2006, Infidel. The next year, Hirsi Ali became a permanent resident in the U.S. and a Fellow of the conservative American Enterprise Institute. About Islam, she says in her 2006 autobiography—

The only position that leaves me with no cognitive dissonance is atheism. It is not a creed. … Islam was like a mental cage. … By declaring our Prophet infallible and not permitting ourselves to question him, we Muslims had set up a static tyranny. The Prophet Muhammad attempted to legislate every aspect of life. By adhering to his rules of what is permitted and what is forbidden, we Muslims suppressed the freedom to think for ourselves and to act as we chose. We froze the moral outlook of billions of people into the mind-set of the Arab desert in the seventh century. We were not just servants of Allah, we were slaves. … In a well-functioning democracy, the state constitution is considered more important than God’s holy book, whichever holy book that may be, and God matters only in your private life.

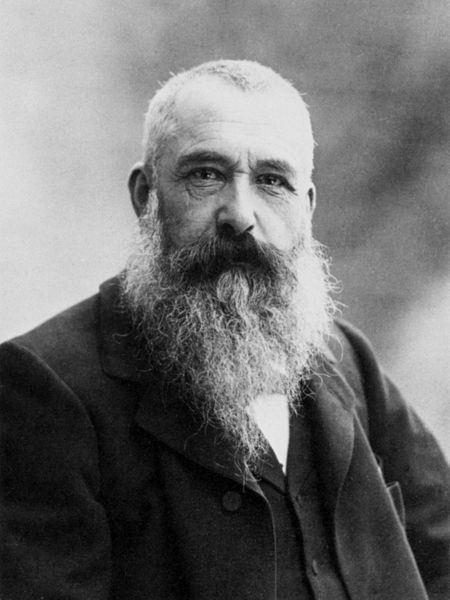

Last Thursday, November 14, but in 1840, the founder of French impressionist painting, Claude Monet was born. The term “Impressionism” is derived from the title of his 1872 painting Impression, Sunrise. From his earliest days, Claude-Oscar Monet wanted to paint. He found his way to Paris, where he befriended fellow painter Édouard Manet and met Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley. Monet eventually moved to a house in Giverny in Normandy, where he painted for much of the latter part of his life. He died a wealthy man on 5 December 1926 at the age of 86, having outlived two wives. Far from being inspired by God or the Catholic faith he abandoned in his early years, Monet once mused, “The richness I achieve comes from nature, the source of my inspiration” and “It’s on the strength of observation and reflection that one finds a way. So we must dig and delve unceasingly.” Art critic Steven Z. Levine, in his 1994 work Monet, Narcissus, and Self-Reflection likens Monet’s atheism to that of Schopenhauer. Ruth Butler, in her 2008 work Hidden in the Shadow of the Master, writes, “Monet took the end of his brush and drew some long straight strokes in the wet pigment across her chest. It's not clear, and probably not consciously intended by the atheist Claude Monet, but somehow the suggestion of a Cross lies there on her body.” It was Claude Monet who, in effect denying any supernatural solace in this world, said, “The noblest pleasure is the joy of understanding.”

Yesterday, November 15, but in 1280, the greatest German philosopher and theologian of the Middle Ages, Albertus Magnus (or Albert the Great) died. Albert was born about 1206, the son of the Count of Bollstädt, and made his early studies at the University of Padua, where Latin translations from Greek of Aristotle, and where the science of such Arab Aristotelians as Avicenna (960-1017) and Averroës (1126-1198), were well known – and original work by non-Arab scientists, except for Albert’s contemporary and intellectual superior, Roger Bacon (1214-1292), was unknown. Albert is often held up as proof that the medieval Church never opposed or retarded science. Albert was a Dominican monk, and as the “Universal Doctor” too famous to be persecuted – unlike the unlucky Bacon, who was imprisoned for his lack of orthodoxy. Albert was only criticized by his colleagues. But the telling fact about Albert is that, aside from Thomas Aquinas (1224-1274), who failed to learn any science from his teacher, when Albert died he left behind no pupils to follow his work. The sterility of science was further assured by the Church thereafter enjoining the Dominicans to turn their minds toward theology instead.

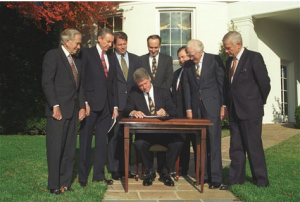

Today, November 16, but in 1993, the U.S. Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. RFRA, as it is called, was introduced in March 1993 and was aimed at preventing laws that substantially burden a person's free exercise of their religion. Although invalidated at the state level by a Supreme Court decision in 1997 (City of Boerne v. Flores), at the federal level the law reinstated the Sherbert Test, mandating that in determining if the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution has been violated, strict scrutiny must be applied. The assumption behind the Act is that religious freedom somehow needs to be restored – in a society in which presidents routinely hold prayer breakfasts and declare a National Day of Prayer, in which Congress has a taxpayer-paid chaplain, in which “In God We Trust” is on all its currency, in which you can’t swing a dead cat without hitting a church, in which workers have no trouble getting time off for religious holidays, in which churches routinely pay no taxes and in which laws favoring solely religious opinion (such as those restricting abortion, contraception and same-sex marriage, as well as the teaching of evolution theory in public schools)!

Basically, RFRA is used to try to beat back advancing secularization of laws and government functions in society by casting disputes as Free Exercise violations to counter Establishment of Religion violations. Some examples: RFRA is being used to reinstate Section 3 of the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), declared unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court (essentially allowing same-sex couples who are legally married in their own states to receive federal benefits); RFRA is being used to allow employers to escape the contraception mandate under the Affordable Care Act (ObamaCare), even if contraception does not violate the conscience of the employee who is earning the benefit. RFRA could even be used to allow employers to ignore child labor laws, or to refuse to hire married women, or to fire gay employees – simply because these things may violate their religion-based beliefs. Worse, RFRA could be used to “inoculate” parents who deny medical treatment to their children on religious grounds – in some cases actually causing death.

Other birthdays and events this week—

November 10: Germany’s second-greatest poet (after Goethe), Friedrich von Schiller was born (1759).

November 11: Former priest and militant Freethought writer Joseph Martin McCabe was born (1867).

November 13: Scottish essayist, poet, and author of fiction and travel books Robert Louis Stevenson was born (1850).

November 13: The brilliant Roman Catholic Church Father, Augustine of Hippo (Aurelius Augustinus), was born (354).

November 14: The first Prime Minister of independent India, Jawaharlal Nehru (Hindi: जवाहरलाल नेहरू; Urdu: جواهر لال نهرو) was born (1889).

November 14: Pioneering Scottish geologist Charles Lyell was born (1797).

November 15: “The Great Commoner,” English statesman William Pitt the Elder was born (1708).

November 16: The US recognized the USSR, thereby raising the question: Are all Atheists Communists, or are all Communists Atheists? (1933).

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in my blog, FreethoughtAlmanac.com.

[soundcloud url="https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/120498028" width="100%" height="166" iframe="true" /]