This Week in Freethought History (August 25-31)

Here’s your week in Freethought History. This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

Last Sunday, August 25, but in 1978, the famous “Shroud of Turin,” venerated by Catholics as the burial cloth of the crucified Jesus, went on public display for the first time in 45 years. Even the Catholic Encyclopedia is parsimonious in its credulity: “…the claim is made that it is the actual ‘clean linen cloth’ in which Joseph of Arimathea wrapped the body of Jesus Christ (Matthew 27:59).” In 1988, a team of experts from three universities each independently tested and dated the cloth to around 1350. Joe Nickell, who collaborated with scientific and technical experts on his Inquest on the Shroud of Turin (2nd Ed., 1992) and Walter McCrone, a microchemist, in his Judgment Day for the Shroud of Turin (1999), both demonstrate that the shroud is a medieval fake. In his article on the shroud from the Skeptic’s Dictionary, Robert Todd Carroll sums up: “Even if it is established beyond any reasonable doubt that the shroud originated in Jerusalem and was used to wrap up the body of Jesus, so what? Would that prove Jesus rose from the dead? I don’t think so. To believe anyone rose from the dead can’t be based on physical evidence, because resurrection is a physical impossibility.”

Last Monday, August 26, but in 1941, American feminist, democratic socialist, and political activist Barbara Ehrenreich was born. An award-winning columnist and essayist, Ehrenreich has been called “a veteran muckraker” by The New Yorker magazine for such works as her best known Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America (2001), a recounting of her three-month experiment surviving on minimum wage. Notable articles include “Is It Now a Crime to Be Poor?” (2009) and “The New Creationism: Biology Under Attack” (1997). Although she never quite admits to being an atheist, it is evident Barbara Ehrenreich has an entirely godless, secular humanist outlook on life. It was in Nickel and Dimed that Ehrenreich wrote,

Maybe it's low-wage work in general that has the effect of making you feel like a pariah. When I watch TV over my dinner at night, I see a world in which almost everyone makes $15 an hour or more, and I’m not just thinking of the anchor folks. The sitcoms and dramas are about fashion designers or schoolteachers or lawyers, so it’s easy for a fast-food worker or nurse’s aide to conclude that she is an anomaly – the only one, or almost the only one, who hasn’t been invited to the party. And in a sense she would be right: the poor have disappeared from the culture at large, from its political rhetoric and intellectual endeavors as well as from its daily entertainment. Even religion seems to have little to say about the plight of the poor, if that tent revival was a fair sample. The moneylenders have finally gotten Jesus out of the temple.

Last Tuesday, August 27, by tradition, the Chinese teacher and philosopher known as Confucius (孔子) was born. When Confucius was 24, he began traveling about and teaching, usually instructing a small number of disciples he eventually drew to him in the second half of the Zhou dynasty (1027?-256 BC). Confucian philosophy from the Analects (論語) is simple: to love others; to honor one’s forbears; to do what is right instead of what is of advantage; to practice “reciprocity,” i.e., “don’t do to others what you would not want done to yourself” – the reverse of what Christians call the Golden Rule. Confucius never had any pretensions of founding a religion. Confucianism is unique in history as an ethic with no religious content, no mysticism. The term for “god” in his Analects is often translated “spirit” or even “spiritual beings.” Therefore, his advice regarding religions was, “Respect spiritual beings if there are any, but keep away from them.” For more than 2,000 years, since the death of Confucius in 479 BCE, Confucianism has been the general creed of educated Chinese. But it was never a religion.

Last Wednesday, August 28, but in 1749, the great the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was born. The one thing that exists, Hegel said in his 1816 Science of Logic, is Spirit or the Absolute Mind, which is in a state of eternal development: an unfolding of reality in terms of thesis – antithesis – synthesis. However, as to God, “The proofs,” said Hegel, “are to such an extent fallen into discredit that they pass for something antiquated, belonging to days gone by.” Hegel professed to be a Christian in his personal morality, but he despised theology and rejected the idea of a personal god. When he was reminded of Kant’s moral argument for a future life he said, “So you expect a tip for nursing your sick mother and for not poisoning your brother?”

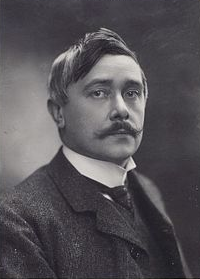

Last Thursday, August 29, but in 1862, Belgian writer and Nobel laureate Maurice Maeterlinck was born. Education under Jesuit control and literary restrictions instilled in Maeterlinck a distaste for the Catholic Church and organized religion generally. At the urging of his father, he studied law at the University of Ghent and practiced until 1896. By then he had moved to Paris and was gaining enthusiastic praise for Intruder (1890), The Blind (1890) and Pelléas and Mélisande (1892), symbolist plays working the themes of death and the meaning of life from the point of view of fatalism. These were followed by his most famous work, The Blue Bird in 1908. For his plays and exquisitely written moral essays, Maeterlinck won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1911. By the time he had written La mort (1913) Maeterlinck had rejected the idea of a future life, although he still dabbled in mysticism. For criticizing the Roman Catholic Church, his entire body of work was placed on the Index of Prohibited Books. Maeterlinck died an unbeliever in Nice, France, on 6 May 1949. There was no priest at his funeral. It was Maurice Maeterlinck who said, “All our knowledge merely helps us to die a more painful death than the animals that know nothing. A day will come when science will turn upon its error and no longer hesitate to shorten our woes. A day will come when it will dare and act with certainty; when life, grown wiser, will depart silently at its hour, knowing that it has reached its term.”

Yesterday, August 30, but in 1930, the multi-billion-dollar investor Warren Buffet was born. The Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway is also known as the “Oracle of Omaha” for his Nebraska-based wisdom in picking market winners. One thing he did not invest in was religion: as biographer Roger Lowenstein says, Buffet “did not subscribe to his family’s religion. … He adopted his father’s ethical underpinnings, but not his belief in an unseen divinity.” “An agnostic like [philosopher and atheist Bertrand] Russell, and deeply aware of his mortality,” writes Lowenstein, “Buffett thought it was up to society, collectively, to protect the planet from dangers such as nuclear war.” Warren Allen Smith, in over six decades of correspondence asking people if they believe in God, culminating in his 2000 book Who’s Who in Hell, got the following one-word answer from Warren Buffet, scrawled on a postcard: “Agnostic.”

Today, August 31, but in 1821, the German physician and physicist Hermann von Helmholtz was born. In an 1847 physics treatise Helmholtz described the law of the conservation of energy. This was in line with his philosophical belief that no deity or “vital principal” was necessary to explain muscle movement. Indeed, as a thorough and outspoken Agnostic, Helmholtz believed medicine would eliminate belief in “mystical disease-entities,” just as Newton and physics would eliminate belief in “astrological superstitions”; likewise, he opposed spiritualism and mysticism. Helmholtz maintained that God was not necessary to the functioning of the universe; that no “act of supernatural intelligence” explains the origin of humanity better than Darwin’s theories.”

Other birthdays and events this week—

August 26: French physiologist and Nobel laureate Charles Richet was born (1850).

August 29: English philosopher John Locke was born (1632).

August 30: The most important European painter of the French Revolutionary period, Jacques-Louis David was born (1748).

August 31: French poet and journalist Théophile Gautier was born (1811).

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in my blog, FreethoughtAlmanac.com.