This Week in Freethought History (June 9-15)

Here’s your week in Freethought History. This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

Last Sunday, June 9, but in 1843, the Austrian novelist, pacifist, and first woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Baroness Bertha von Suttner was born. She was born in Prague, in what is now the Czech Republic, the posthumous daughter of Field Marshal Count Kinsky. Yet, despite the militaristic tradition in which she was reared, Bertha became a peace activist and an international figure in the movement to offer arbitration in place of warfare between nations. Bertha tried to popularize the idea of the Permanent Court of Arbitration. She was the only woman at the First Hague Convention of 1899. Her former employer, Alfred Nobel, had established a peace prize to be awarded after his death, and in 1905 Bertha won this much-deserved award – the first woman to be so honored. It is arguable that no such award would have existed had not Von Suttner and Alfred Nobel been so close. And Baroness von Suttner made no secret of her Rationalism. In her Memoirs, published in 1909, Bertha von Suttner remarked that if she had been asked in her youth to describe her religion, she would have said, “None – I am too religious.” Her beliefs might best be described as Pantheism, seeing God only in nature. She died on 21 June 1914, age 71, two months before the eruption of the world war she had warned and struggled against.

Last Sunday, June 9, but in 1843, the Austrian novelist, pacifist, and first woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Baroness Bertha von Suttner was born. She was born in Prague, in what is now the Czech Republic, the posthumous daughter of Field Marshal Count Kinsky. Yet, despite the militaristic tradition in which she was reared, Bertha became a peace activist and an international figure in the movement to offer arbitration in place of warfare between nations. Bertha tried to popularize the idea of the Permanent Court of Arbitration. She was the only woman at the First Hague Convention of 1899. Her former employer, Alfred Nobel, had established a peace prize to be awarded after his death, and in 1905 Bertha won this much-deserved award – the first woman to be so honored. It is arguable that no such award would have existed had not Von Suttner and Alfred Nobel been so close. And Baroness von Suttner made no secret of her Rationalism. In her Memoirs, published in 1909, Bertha von Suttner remarked that if she had been asked in her youth to describe her religion, she would have said, “None – I am too religious.” Her beliefs might best be described as Pantheism, seeing God only in nature. She died on 21 June 1914, age 71, two months before the eruption of the world war she had warned and struggled against.

Last Monday, June 10, but in 1797, President John Adams signed into law, promising thereby “faithfully to observe and fulfill … every clause and article” the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the United States of America and the Bey and Subjects of Tripoli of Barbary. The Treaty with Tripoli, as it is now known, a regency in what is now Libya, has become a key document in the debate over whether or not the United States is, or ever was, or was intended to be, a Christian nation, or even founded on Christian principles. The questionable clause is from Article 11 of 12. In its entirety, Article 11 reads,

As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion – as it has in itself no character of enmity [hatred] against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen [Muslims] – and as the said States [America] have never entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mahometan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.

One detractor says that the article must be read “as a declaration that the federal government of the United States was not in any sense founded on the Christian religion,” and that “such a statement is not a repudiation of the fact that America was considered a Christian nation.” However, the Declaration of Independence refers only to a creator, not to a Christian God, and the Constitution is conspicuously godless – Jefferson wrote that an attempt was made to insert a reference to Jesus Christ, and that it was voted down. The Treaty with Tripoli was not only adopted unanimously, but there was no debate, no dissention. True, the majority of Americans in 1797 were at least nominally Christian, even if no more than 10 percent of Americans were actually members of congregations. But, no, the United States is no more a Christian nation because most of its citizens are Christians than it is a “white” nation because most of its citizens are white. No religion defines us, just as no race or ethnicity defines us. We are Americans not because we practice revealed religion and believe in Bible-based government, but because we practice democracy and believe in republican government.

One detractor says that the article must be read “as a declaration that the federal government of the United States was not in any sense founded on the Christian religion,” and that “such a statement is not a repudiation of the fact that America was considered a Christian nation.” However, the Declaration of Independence refers only to a creator, not to a Christian God, and the Constitution is conspicuously godless – Jefferson wrote that an attempt was made to insert a reference to Jesus Christ, and that it was voted down. The Treaty with Tripoli was not only adopted unanimously, but there was no debate, no dissention. True, the majority of Americans in 1797 were at least nominally Christian, even if no more than 10 percent of Americans were actually members of congregations. But, no, the United States is no more a Christian nation because most of its citizens are Christians than it is a “white” nation because most of its citizens are white. No religion defines us, just as no race or ethnicity defines us. We are Americans not because we practice revealed religion and believe in Bible-based government, but because we practice democracy and believe in republican government.

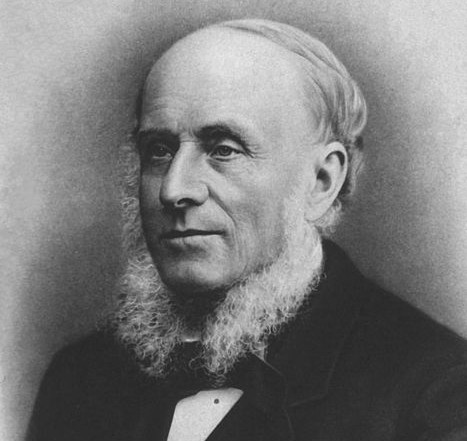

Last Tuesday, June 11, but in 1818, the Scottish psychologist, philosopher and educator Alexander Bain was born. Bain was one of the foremost psychologists and educationists of the 19th century. In spite of religious hostility to his naturalist conclusions in the science of mind, he was made professor of logic and English at Aberdeen University from 1860 to 1880, and twice elected Lord Rector (1882, 1884). His chief works on psychology (Senses and the Intellect, 1855; Emotions and the Will, 1859; and Mind and Body, 1873) were regarded as classics for several decades, and in 1876, at his own expense, Bain established the review Mind, the first-ever journal of psychology and analytical philosophy. He helped John Stuart Mill revise his System of Logic (1842). Bain was an Agnostic, and is wrongly described sometimes as a Positivist. He merely agreed with Comte in the rejection of theology. He died at age 85 in Aberdeen on 18 September 1903. His last request, according to a New York Times obituary, was that “no stone should be placed upon his grave: his books, he said, would be his monument.”

Last Tuesday, June 11, but in 1818, the Scottish psychologist, philosopher and educator Alexander Bain was born. Bain was one of the foremost psychologists and educationists of the 19th century. In spite of religious hostility to his naturalist conclusions in the science of mind, he was made professor of logic and English at Aberdeen University from 1860 to 1880, and twice elected Lord Rector (1882, 1884). His chief works on psychology (Senses and the Intellect, 1855; Emotions and the Will, 1859; and Mind and Body, 1873) were regarded as classics for several decades, and in 1876, at his own expense, Bain established the review Mind, the first-ever journal of psychology and analytical philosophy. He helped John Stuart Mill revise his System of Logic (1842). Bain was an Agnostic, and is wrongly described sometimes as a Positivist. He merely agreed with Comte in the rejection of theology. He died at age 85 in Aberdeen on 18 September 1903. His last request, according to a New York Times obituary, was that “no stone should be placed upon his grave: his books, he said, would be his monument.”

Also last Tuesday, June 11, but in 1959, the English actor, comedian, and writer, best known as star of the television show “House, MD,” Hugh Laurie was born. He was active in the 1980s and 1990s as half of a comedy duo, Fry and Laurie, performing with longtime friend and fellow atheist Stephen Fry. The two also performed Jeeves and Wooster (with Laurie playing Wooster). Before the 2004-2012 TV series that made him famous (and the highest paid actor ever in a television drama), Laurie appeared in the films Sense and Sensibility (1995, adapted by friend and co-star Emma Thompson), the live-action film 101 Dalmatians (1996), and the three Stuart Little films (1999, 2002, 2006). But after auditioning from a bathroom, and convincing producer David Shore that he speaks “American” better than all the other actors who auditioned for the title character, Laurie was cast as the “antisocial maverick doctor who specializes in diagnostic medicine [who] does whatever it takes to solve puzzling cases that come his way using his crack team of doctors and his wits.” The “House, M.D.” TV series ran eight seasons on Fox. From the first, it is clear that Dr. Gregory House is an atheist, but what of the actor?

Also last Tuesday, June 11, but in 1959, the English actor, comedian, and writer, best known as star of the television show “House, MD,” Hugh Laurie was born. He was active in the 1980s and 1990s as half of a comedy duo, Fry and Laurie, performing with longtime friend and fellow atheist Stephen Fry. The two also performed Jeeves and Wooster (with Laurie playing Wooster). Before the 2004-2012 TV series that made him famous (and the highest paid actor ever in a television drama), Laurie appeared in the films Sense and Sensibility (1995, adapted by friend and co-star Emma Thompson), the live-action film 101 Dalmatians (1996), and the three Stuart Little films (1999, 2002, 2006). But after auditioning from a bathroom, and convincing producer David Shore that he speaks “American” better than all the other actors who auditioned for the title character, Laurie was cast as the “antisocial maverick doctor who specializes in diagnostic medicine [who] does whatever it takes to solve puzzling cases that come his way using his crack team of doctors and his wits.” The “House, M.D.” TV series ran eight seasons on Fox. From the first, it is clear that Dr. Gregory House is an atheist, but what of the actor?

About his upbringing, Hugh Laurie notes that “belief in God didn't play a large role in my home, but a certain attitude to life and the living of it did.” He has declared (The Daily Telegraph – “Man about the House” 10/28/2007): “I don’t believe in God, but I have this idea that if there were a God, or destiny of some kind looking down on us, that if he saw you taking anything for granted he’d take it away.” In a 7/31/2006 appearance on “Inside the Actors Studio,” host James Lipton asked Laurie, “Do you share Houses’s skepticism?” Laurie replied, laughing, “I do. Big chunks of it, yes. I’m not a religious man. Again, I think this is connected to my father. My father was religious, oddly enough, but I nonetheless I suppose I was impressed by, enamored of his devotion to medical science. I find I am a fan of science. I believe in science. A humility before the facts. I find that a moving and beautiful thing. And belief in the unknown I find less interesting. I find the known and the knowable interesting enough.” During the British chat show, “God Almighty,” in which celebrities describe what they would do to change the world if they were God (3/11/2003), a member asked, “Who would you create first, woman or man?” Hugh Laurie replied, “Oh, um. I see pitfalls either way. But see, the other problem I have, is that, being an atheist [audience laughs], is regards to this whole exercise is, it holds me back a bit. Unless I start to appear in people’s visions and tell them that ‘I don’t exist’ ... think about that!”

Last Wednesday, June 12, but in 1381, the Peasants’ Revolt or Great Rising of 1381, also known as Wat Tyler’s Rebellion, began. Geoffrey Chaucer was about 41. The 1300s, or what historian Barbara Tuchman calls “The Calamitous 14th Century,” was theoretically an Age of Chivalry, but in fact a time of superstition, faith, plague, great cathedrals, great poverty, great ignorance, brutal punishment (visited with a vengeance on the peasantry), sexual license and corruption, especially in the Church.. Wat Tyler, who lived in Maidstone, Essex, was outraged when an overzealous tax collector sought to determine if Tyler’s daughter was of taxable age (15). He stripped the girl naked and sexually assaulted her. With a hammer, Tyler smashed in the tax collector’s skull. His fellow peasants cheered this action. They banded together to seek redress from the king. Tyler’s group was joined by two secular priests named John Ball and Jack Straw. Their party eventually numbered 100,000 strong and converged on London. But the rebels, still in the grip of the myth of the “divine right” of kings, believed young King Richard II a natural ally of the poor. On June 14 Richard met with Wat Tyler and ordered the Lord Mayor of London to “set hands on him.” Tyler was murdered on the spot. Richard declared, “Wat Tyler was a traitor. I’ll be your leader.” The teenaged monarch immediately agreed to all the rebel demands – chiefly, the abolition of serfdom – and everybody went home. Thereupon the king reneged on his promises and hunted down and hanged 1500 of the rebels. So the oppression of the peasants persisted. And Richard, king of England by divine right, declared to the peasants seeking an end to their slavery, “Villeins ye are, and villeins ye shall remain.”

Last Wednesday, June 12, but in 1381, the Peasants’ Revolt or Great Rising of 1381, also known as Wat Tyler’s Rebellion, began. Geoffrey Chaucer was about 41. The 1300s, or what historian Barbara Tuchman calls “The Calamitous 14th Century,” was theoretically an Age of Chivalry, but in fact a time of superstition, faith, plague, great cathedrals, great poverty, great ignorance, brutal punishment (visited with a vengeance on the peasantry), sexual license and corruption, especially in the Church.. Wat Tyler, who lived in Maidstone, Essex, was outraged when an overzealous tax collector sought to determine if Tyler’s daughter was of taxable age (15). He stripped the girl naked and sexually assaulted her. With a hammer, Tyler smashed in the tax collector’s skull. His fellow peasants cheered this action. They banded together to seek redress from the king. Tyler’s group was joined by two secular priests named John Ball and Jack Straw. Their party eventually numbered 100,000 strong and converged on London. But the rebels, still in the grip of the myth of the “divine right” of kings, believed young King Richard II a natural ally of the poor. On June 14 Richard met with Wat Tyler and ordered the Lord Mayor of London to “set hands on him.” Tyler was murdered on the spot. Richard declared, “Wat Tyler was a traitor. I’ll be your leader.” The teenaged monarch immediately agreed to all the rebel demands – chiefly, the abolition of serfdom – and everybody went home. Thereupon the king reneged on his promises and hunted down and hanged 1500 of the rebels. So the oppression of the peasants persisted. And Richard, king of England by divine right, declared to the peasants seeking an end to their slavery, “Villeins ye are, and villeins ye shall remain.”

Last Thursday, June 13, but in 1865, Irish poet and one of the foremost figures of 20th century literature, William Butler Yeats was born. Yeats’s poetry is influenced by the English Romantic tradition and by his fascination with the occult, following his study of William Blake and Emanuel Swedenborg. His occult preoccupations were encouraged by his wife, Georgie Hyde Lees, a supposed spirit medium, whom Yeats married in 1917 when she was half his age. Yeats helped to found the Irish Literary Theater in 1899 (later the Abbey Theater) and led the Irish literary movement. The Irish State rewarded Yeats with a Senate seat, 1922-1928; the world recognized his talents with the Nobel prize for literature in 1923. Yeats cannot properly be claimed by any Christian sect. In his 1903 volume of literary and critical essays, Ideas of Good and Evil, Yeats speaks of “divine love in sexual passion” and says that “the great passions are angels of God.” While less mystical than Blake, he believed in a “supersensible world” — one beyond the senses, and at the same time criticized Christianity. In his poem, “The Second Coming,” Yeats mixes pagan and Christian symbolism in a horror-filled vision of the rebirth of paganism from a dead Christianity. Yeats opposed the adoption of Article 44 of the Irish Constitution in 1937 – which says, “The State acknowledges that the homage of public worship is due to Almighty God. It shall hold His Name in reverence, and shall respect and honour religion.” – saying, “Once you attempt legislation on religious grounds, you open the way for every kind of intolerance and religious persecution.”

Last Thursday, June 13, but in 1865, Irish poet and one of the foremost figures of 20th century literature, William Butler Yeats was born. Yeats’s poetry is influenced by the English Romantic tradition and by his fascination with the occult, following his study of William Blake and Emanuel Swedenborg. His occult preoccupations were encouraged by his wife, Georgie Hyde Lees, a supposed spirit medium, whom Yeats married in 1917 when she was half his age. Yeats helped to found the Irish Literary Theater in 1899 (later the Abbey Theater) and led the Irish literary movement. The Irish State rewarded Yeats with a Senate seat, 1922-1928; the world recognized his talents with the Nobel prize for literature in 1923. Yeats cannot properly be claimed by any Christian sect. In his 1903 volume of literary and critical essays, Ideas of Good and Evil, Yeats speaks of “divine love in sexual passion” and says that “the great passions are angels of God.” While less mystical than Blake, he believed in a “supersensible world” — one beyond the senses, and at the same time criticized Christianity. In his poem, “The Second Coming,” Yeats mixes pagan and Christian symbolism in a horror-filled vision of the rebirth of paganism from a dead Christianity. Yeats opposed the adoption of Article 44 of the Irish Constitution in 1937 – which says, “The State acknowledges that the homage of public worship is due to Almighty God. It shall hold His Name in reverence, and shall respect and honour religion.” – saying, “Once you attempt legislation on religious grounds, you open the way for every kind of intolerance and religious persecution.”

Yesterday, June 14, but in 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed a Congressional resolution which added the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance. The pledge, which Congress had recognized officially only a dozen years earlier, was originally written in August of 1892 by Francis Bellamy (1855-1931), a Baptist minister, and active Socialist. The Pledge was first published in a children’s magazine, Youth’s Companion, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas. The original 22 words were: “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” It was the 1950 and people and politicians were looking for ways to distinguish god-fearing Americans from those atheistic Communists in Russia. On April 22, 1951, the Board of Directors of the Roman Catholic men’s group, the Knights of Columbus, mounted a campaign to add the words “under God,” after the words “one nation,” in the Pledge. A bill to add “God” to the Pledge was approved as a Congressional joint resolution on 8 June 1954. It was signed into law on that Flag Day, June 14. President Eisenhower, who started the tradition of the “prayer breakfast,” said at the time, “From this day forward, the millions of our school children will daily proclaim in every city and town, every village and rural schoolhouse, the dedication of our Nation and our people to the Almighty…” It is odd, therefore, that when the United States Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit decided, on 26 June 2002, that the words “under God” made the Pledge run afoul of the establishment clause of the First Amendment, they rejected the changed Pledge for the same reason that President Eisenhower accepted it: because it was a government endorsement of religion!

Yesterday, June 14, but in 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed a Congressional resolution which added the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance. The pledge, which Congress had recognized officially only a dozen years earlier, was originally written in August of 1892 by Francis Bellamy (1855-1931), a Baptist minister, and active Socialist. The Pledge was first published in a children’s magazine, Youth’s Companion, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas. The original 22 words were: “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” It was the 1950 and people and politicians were looking for ways to distinguish god-fearing Americans from those atheistic Communists in Russia. On April 22, 1951, the Board of Directors of the Roman Catholic men’s group, the Knights of Columbus, mounted a campaign to add the words “under God,” after the words “one nation,” in the Pledge. A bill to add “God” to the Pledge was approved as a Congressional joint resolution on 8 June 1954. It was signed into law on that Flag Day, June 14. President Eisenhower, who started the tradition of the “prayer breakfast,” said at the time, “From this day forward, the millions of our school children will daily proclaim in every city and town, every village and rural schoolhouse, the dedication of our Nation and our people to the Almighty…” It is odd, therefore, that when the United States Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit decided, on 26 June 2002, that the words “under God” made the Pledge run afoul of the establishment clause of the First Amendment, they rejected the changed Pledge for the same reason that President Eisenhower accepted it: because it was a government endorsement of religion!

Today, June 15, but in 1520, Pope Leo X (p. 1513-1521) issued the Bull Exsurge Domine (Arise, O Lord), condemning Martin Luther for forty-one doctrinal errors and threatening him with excommunication if he would not recant. If Martin Luther (1483-1546) needed any more evidence that the Papacy was luxuriously corrupt, he had only to look to the current occupant of the Chair of St. Peter. Consuming a surplus acquired by his predecessor, Leo X (r. 1513-1521) spent lavishly on banquets, entertainments, jewels and gifts – to the tune of five million ducats, in excess of $33 million in today’s currency, over eight years. He was lying and duplicitous in diplomacy and raised money through the sale of offices and indulgences, which combined simony with nepotism. So it was this Pope who condemned the errors of Martin Luther, such as that “Indulgences are pious frauds of the faithful, and remissions of good works” (18); and that “The Roman Pontiff, the successor of Peter, is not the vicar of Christ over all the churches of the entire world, instituted by Christ Himself in blessed Peter” (25); or to say “That heretics be burned is against the will of the Spirit” (33). Threatening to cut him off from the Catholic community in the 1520 Bull, Leo finally excommunicated Luther on 3 January 1521. At last Leo succumbed to a poisoning on 1 Dec 1521, although modern Catholic historians dispute the physicians who actually saw the dark and swollen body. Inhibited by neither Exsurge Domine nor his excommunication, Martin Luther outlived the next two Popes.

Today, June 15, but in 1520, Pope Leo X (p. 1513-1521) issued the Bull Exsurge Domine (Arise, O Lord), condemning Martin Luther for forty-one doctrinal errors and threatening him with excommunication if he would not recant. If Martin Luther (1483-1546) needed any more evidence that the Papacy was luxuriously corrupt, he had only to look to the current occupant of the Chair of St. Peter. Consuming a surplus acquired by his predecessor, Leo X (r. 1513-1521) spent lavishly on banquets, entertainments, jewels and gifts – to the tune of five million ducats, in excess of $33 million in today’s currency, over eight years. He was lying and duplicitous in diplomacy and raised money through the sale of offices and indulgences, which combined simony with nepotism. So it was this Pope who condemned the errors of Martin Luther, such as that “Indulgences are pious frauds of the faithful, and remissions of good works” (18); and that “The Roman Pontiff, the successor of Peter, is not the vicar of Christ over all the churches of the entire world, instituted by Christ Himself in blessed Peter” (25); or to say “That heretics be burned is against the will of the Spirit” (33). Threatening to cut him off from the Catholic community in the 1520 Bull, Leo finally excommunicated Luther on 3 January 1521. At last Leo succumbed to a poisoning on 1 Dec 1521, although modern Catholic historians dispute the physicians who actually saw the dark and swollen body. Inhibited by neither Exsurge Domine nor his excommunication, Martin Luther outlived the next two Popes.

Other birthdays and events this week—

June 11: The German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, Richard Strauss was born (1864).

June 11: The Jacobean playwright, poet, and literary critic, Ben Jonson was born (1572).

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in my blog, FreethoughtAlmanac.com.