This Week in Freethought History (May 5-11)

Here’s your Week in Freethought History: This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

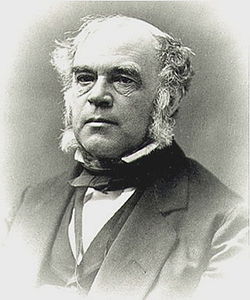

Last Sunday, May 5, but in 1811, English-born American physician, chemist and historian, John William Draper was born. It was his 1874 History of the Conflict between Religion and Science, preceding the two-volume work of Andrew Dickson White’s by 11 years, that stirred the notion that religion and science are irreconcilable. In his introduction, he writes, “The antagonism we … witness between Religion and Science is the continuation of a struggle that commenced when Christianity began to attain political power. … [F]aith is in its nature unchangeable, stationary; Science is in its nature progressive; and eventually a divergence between them … must take place. … As to Science, … she has never subjected any one to mental torment, physical torture, least of all to death, for the purpose of upholding or promoting her ideas.” Although Draper believed in God and life after death, his skepticism toward organized religion (Lindberg and Numbers, 1986, accused him of “strident anti-Catholicism”) made him a Freethinker until the day he died.

Last Sunday, May 5, but in 1811, English-born American physician, chemist and historian, John William Draper was born. It was his 1874 History of the Conflict between Religion and Science, preceding the two-volume work of Andrew Dickson White’s by 11 years, that stirred the notion that religion and science are irreconcilable. In his introduction, he writes, “The antagonism we … witness between Religion and Science is the continuation of a struggle that commenced when Christianity began to attain political power. … [F]aith is in its nature unchangeable, stationary; Science is in its nature progressive; and eventually a divergence between them … must take place. … As to Science, … she has never subjected any one to mental torment, physical torture, least of all to death, for the purpose of upholding or promoting her ideas.” Although Draper believed in God and life after death, his skepticism toward organized religion (Lindberg and Numbers, 1986, accused him of “strident anti-Catholicism”) made him a Freethinker until the day he died.

Outliving Draper, however, was an idea, inspired by the title of his 1874 work but further developed by Andrew Dickson White in his 1895 History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom, known as the “Conflict Thesis.” Although modern scholars, as Wikipedia would have us believe, consider “Conflict” impolite if not downright antagonistic to religion, the Conflict Thesis is essentially correct as Draper and White formulated it. Critics seem to assume that Draper and White were not first-rate scholars in their own right, or that because they wrote in the 19th century, their scholarship has been invalidated by that of the 20th century. Both assumptions are false, even (perhaps especially) if you accept the “non-overlapping magisterial” (NOMA) view advocated by Stephen Jay Gould – that science and religion each have “a legitimate magisterium, or domain of teaching authority,” and these two domains do not overlap.

Anyone who has read Draper and White, and independently verified their sources, would be hard pressed to fault White on his scholarship and the thoroughness of his research. Their conclusions seem to be ratified by modern scientists, such as Dawkins and Hawking, who are not tempted to make peace with the hostile tribes for the sole purpose of “live and let live.” Some critics of the Conflict Thesis, such as Science & Religion (ed. Ferngren, 2002), Science and Religion (Brooke, 1991) and God and Nature (Lindberg, Numbers, 1986), feature arguments that run the gamut from ahistorical to silly straw men. The consistent mistake is their refusal to see that religion, i.e., religious faith, is not and never has been a way of “knowing” anything. Religion is rather wishful thinking tied with a bow of science-stopping authoritarianism. Science and religion are always in conflict because one is falsifiable and the other is … religion.

Last Monday, May 6, but in 1856, Austrian neurologist and (much caricatured) founding father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud was born. Freud founded modern psychoanalysis and guided the systematic study of neuroses out of the supernatural realm of demon-possession and into the science of physical causes of mental maladies. And Freud turned the old theory on its head, considering religion the disease rather than the cure of mental problems. In 1927, Freud wrote, “Religion … comprises a system of wishful illusions together with a disavowal of reality, such as we find in an isolated form nowhere else but in amnesia, in a state of blissful hallucinatory confusion.” In his last published work, Moses and Monotheism (1939), Freud wrote, “Religion is an attempt to get control over the sensory world … If one attempts to assign to religion its place in man’s evolution, it seems not so much to be a lasting acquisition, as a parallel to the neurosis which the civilized individual must pass through on his way from childhood to maturity.” In a letter to Charles Singer, Freud wrote, “Neither in my private life nor in my writings, have I ever made a secret of being an out-and-out unbeliever.”

Last Monday, May 6, but in 1856, Austrian neurologist and (much caricatured) founding father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud was born. Freud founded modern psychoanalysis and guided the systematic study of neuroses out of the supernatural realm of demon-possession and into the science of physical causes of mental maladies. And Freud turned the old theory on its head, considering religion the disease rather than the cure of mental problems. In 1927, Freud wrote, “Religion … comprises a system of wishful illusions together with a disavowal of reality, such as we find in an isolated form nowhere else but in amnesia, in a state of blissful hallucinatory confusion.” In his last published work, Moses and Monotheism (1939), Freud wrote, “Religion is an attempt to get control over the sensory world … If one attempts to assign to religion its place in man’s evolution, it seems not so much to be a lasting acquisition, as a parallel to the neurosis which the civilized individual must pass through on his way from childhood to maturity.” In a letter to Charles Singer, Freud wrote, “Neither in my private life nor in my writings, have I ever made a secret of being an out-and-out unbeliever.”

Last Tuesday, May 7, but in 1711, Scottish philosopher, economist and essayist, known for his empiricism and skepticism, David Hume was born. Hume professed a belief in God. However, when he applied the scientific method to determining how knowledge is acquired, and formulated the theory that all knowledge is subjective, he pretty much undercut the basis for even Deism. In his Natural History of Religion, he wrote, “Examine the religious principles which have, in fact, prevailed in the world, and you will scarcely be persuaded that they are anything but sick men’s dreams.” Hume was friends with Adam Smith and James Boswell. It was Boswell who attended him as Hume lay dying in 1776 and, hoping to convert him at last, was frustrated when Hume said flatly that “the morality of every religion was bad” and that “when he heard a man was religious, he concluded that he was a rascal.”

Last Tuesday, May 7, but in 1711, Scottish philosopher, economist and essayist, known for his empiricism and skepticism, David Hume was born. Hume professed a belief in God. However, when he applied the scientific method to determining how knowledge is acquired, and formulated the theory that all knowledge is subjective, he pretty much undercut the basis for even Deism. In his Natural History of Religion, he wrote, “Examine the religious principles which have, in fact, prevailed in the world, and you will scarcely be persuaded that they are anything but sick men’s dreams.” Hume was friends with Adam Smith and James Boswell. It was Boswell who attended him as Hume lay dying in 1776 and, hoping to convert him at last, was frustrated when Hume said flatly that “the morality of every religion was bad” and that “when he heard a man was religious, he concluded that he was a rascal.”

Last Wednesday, May 8, but in 1737, English historian and Member of Parliament, Edward Gibbon was born. His father died in 1770, leaving Gibbon enough money to begin writing the first volume of his masterwork, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, which appeared in 1776-1788. It was Gibbon’s aim to elevate history above “the register of the crimes, follies and misfortunes of mankind,” and to wrest the study of the past from clerical confines. He outraged the clerics of his time by describing Christianity as a factor that hastened the decay of Ancient Rome. Gibbon wrote, “… the church and even the state were distracted by religious factions, whose conflicts were sometimes bloody and always implacable; the attention of the emperors was diverted from camps to synods; the Roman world was oppressed by a new species of tyranny, and the persecuted sects became the secret enemies of their country.” Although Gibbon is accused of Atheism and of bias against religion, in his master work he is more charitable toward Christianity than it deserves.

Last Wednesday, May 8, but in 1737, English historian and Member of Parliament, Edward Gibbon was born. His father died in 1770, leaving Gibbon enough money to begin writing the first volume of his masterwork, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, which appeared in 1776-1788. It was Gibbon’s aim to elevate history above “the register of the crimes, follies and misfortunes of mankind,” and to wrest the study of the past from clerical confines. He outraged the clerics of his time by describing Christianity as a factor that hastened the decay of Ancient Rome. Gibbon wrote, “… the church and even the state were distracted by religious factions, whose conflicts were sometimes bloody and always implacable; the attention of the emperors was diverted from camps to synods; the Roman world was oppressed by a new species of tyranny, and the persecuted sects became the secret enemies of their country.” Although Gibbon is accused of Atheism and of bias against religion, in his master work he is more charitable toward Christianity than it deserves.

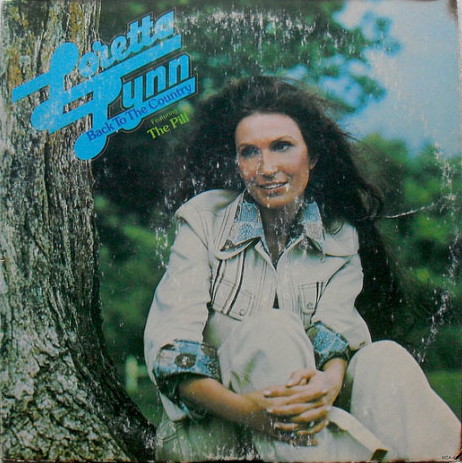

Last Thursday, May 9, but in 1960, the Food & Drug Administration approved the first oral contraceptive, now known as “The Pill”. The effect on sexual freedom for women, a freedom until that time enjoyed only by men, was astonishing. The pill was envisioned by legendary birth control crusader Margaret Sanger. Sanger was in her 80s in 1953 when she met with Roman Catholic Dr. Gregory Pincus (1903-1967). She gave him $150,000 and tasked him to research and develop an oral contraceptive for women that was safe and effective. In defiance of his church, and amid much negative publicity for attempting to thwart God’s will – a will Sanger once described as “biological slavery” – Dr. Pincus succeeded. The reaction of the churches was predictably punitive. The reaction of the Catholic Church in particular was to cobble together reasons why “artificial” forms of birth control were bad and “natural” birth control – also known as death – was good. The result, an encyclical from Pope Paul VI in 1968, known as Humanae Vitae (Human Life), was a masterpiece of mendacity and slippery scholarship.

Last Thursday, May 9, but in 1960, the Food & Drug Administration approved the first oral contraceptive, now known as “The Pill”. The effect on sexual freedom for women, a freedom until that time enjoyed only by men, was astonishing. The pill was envisioned by legendary birth control crusader Margaret Sanger. Sanger was in her 80s in 1953 when she met with Roman Catholic Dr. Gregory Pincus (1903-1967). She gave him $150,000 and tasked him to research and develop an oral contraceptive for women that was safe and effective. In defiance of his church, and amid much negative publicity for attempting to thwart God’s will – a will Sanger once described as “biological slavery” – Dr. Pincus succeeded. The reaction of the churches was predictably punitive. The reaction of the Catholic Church in particular was to cobble together reasons why “artificial” forms of birth control were bad and “natural” birth control – also known as death – was good. The result, an encyclical from Pope Paul VI in 1968, known as Humanae Vitae (Human Life), was a masterpiece of mendacity and slippery scholarship.

But where tiresome scholarship and dry historical narrative fail to make the point, it was for country music singer Loretta Lynn to clarify the salutary effect on real women’s lives by sharing her own story, that of a wife liberated from annual pregnancies. In 1975, Lynn released the chart-topping song called simply, “The Pill,” perhaps for the first time frankly publicizing the then-controversial idea of liberation for women through contraception. Many country-western radio stations were so scandalized they refused to play the song, but a number of rural physicians admitted that “The Pill” (in music form) had done more to publicize the availability of birth control in isolated areas than all the literature they had released. In fact, the modern world, with its longer lives, survival of women through their childbearing years and material prosperity, is only possible through such “artificial” impositions on God’s plan: The contraceptive pill, and that other artificial stuff humans created, are all that stand between a humane habitation of planet Earth and devastation by overpopulation.

But where tiresome scholarship and dry historical narrative fail to make the point, it was for country music singer Loretta Lynn to clarify the salutary effect on real women’s lives by sharing her own story, that of a wife liberated from annual pregnancies. In 1975, Lynn released the chart-topping song called simply, “The Pill,” perhaps for the first time frankly publicizing the then-controversial idea of liberation for women through contraception. Many country-western radio stations were so scandalized they refused to play the song, but a number of rural physicians admitted that “The Pill” (in music form) had done more to publicize the availability of birth control in isolated areas than all the literature they had released. In fact, the modern world, with its longer lives, survival of women through their childbearing years and material prosperity, is only possible through such “artificial” impositions on God’s plan: The contraceptive pill, and that other artificial stuff humans created, are all that stand between a humane habitation of planet Earth and devastation by overpopulation.

Yesterday, May 10, but in 1933, Nazi book burning. This particular suppression of free speech and ideas was a tactic of Joseph Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda. But the burning of books, often culminating in the burning of people (as Heinrich Heine famously observed), is an old idea. Chinese Emperor Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇) – who created and then buried the famous Terra Cotta Warriors in Xi’an, China – before he died in 210 BCE, ordered the burning of most extant books. Just to be sure, he had the leading scholars executed, too. In Christendom, John Calvin was probably the most efficient when, in 1600, he burned Michael Servetus at the stake for heresy, and “around his waist were tied a large bundle of manuscripts and a thick octavo printed book.” After America and her allies invaded Iraq in 2003, Iraq's national library and the Islamic library in central Baghdad were burned and destroyed. In early March 2001, about 200 right-wing Hindus burned Korans in New Delhi. In May 1981 Sinhalese police officers burned the second largest library in Asia, in northern Sri Lanka, destroying 97,000 books. The largest single act of book burning in modern history took place in August 1992, when the Oriental Institute in Sarajevo was attacked by Serb nationalist forces, who immolated the National and University Library of Bosnia, destroying a priceless collection of over 1.5 million volumes. But it’s the same old story as when the Nazis burned books on this date 79 years ago: “We know better than you do what’s best for you to read.”

Yesterday, May 10, but in 1933, Nazi book burning. This particular suppression of free speech and ideas was a tactic of Joseph Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda. But the burning of books, often culminating in the burning of people (as Heinrich Heine famously observed), is an old idea. Chinese Emperor Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇) – who created and then buried the famous Terra Cotta Warriors in Xi’an, China – before he died in 210 BCE, ordered the burning of most extant books. Just to be sure, he had the leading scholars executed, too. In Christendom, John Calvin was probably the most efficient when, in 1600, he burned Michael Servetus at the stake for heresy, and “around his waist were tied a large bundle of manuscripts and a thick octavo printed book.” After America and her allies invaded Iraq in 2003, Iraq's national library and the Islamic library in central Baghdad were burned and destroyed. In early March 2001, about 200 right-wing Hindus burned Korans in New Delhi. In May 1981 Sinhalese police officers burned the second largest library in Asia, in northern Sri Lanka, destroying 97,000 books. The largest single act of book burning in modern history took place in August 1992, when the Oriental Institute in Sarajevo was attacked by Serb nationalist forces, who immolated the National and University Library of Bosnia, destroying a priceless collection of over 1.5 million volumes. But it’s the same old story as when the Nazis burned books on this date 79 years ago: “We know better than you do what’s best for you to read.”

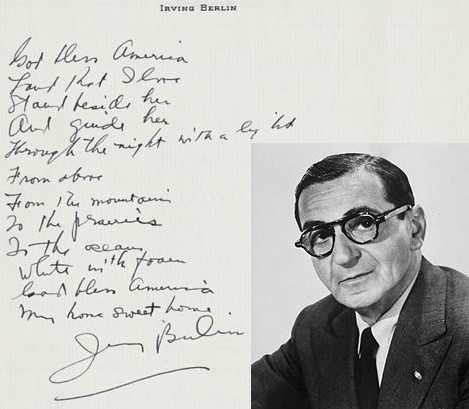

Today, May 11, but in 1888, Russian-born American composer and lyricist, Irving Berlin was born. He emigrated from Russia at the age of five and spent his next 95 years becoming one of the most celebrated film and stage songwriters in US history. Berlin wrote perhaps 1,500 songs, including the scores for 19 Broadway shows and 18 Hollywood films. His songs for film were nominated eight times for Academy Awards, including (perhaps surprisingly for a Jew) “Easter Parade,” “White Christmas” and “Happy Holiday.” In her biography of her father, daughter Mary Ellin Barrett refers to the “agnosticism” of the composer of “God Bless America” and describes him as a “nonbeliever.” Irving Berlin follows a long tradition of freethinkers who used the religious vocabulary familiar to the majority.

Today, May 11, but in 1888, Russian-born American composer and lyricist, Irving Berlin was born. He emigrated from Russia at the age of five and spent his next 95 years becoming one of the most celebrated film and stage songwriters in US history. Berlin wrote perhaps 1,500 songs, including the scores for 19 Broadway shows and 18 Hollywood films. His songs for film were nominated eight times for Academy Awards, including (perhaps surprisingly for a Jew) “Easter Parade,” “White Christmas” and “Happy Holiday.” In her biography of her father, daughter Mary Ellin Barrett refers to the “agnosticism” of the composer of “God Bless America” and describes him as a “nonbeliever.” Irving Berlin follows a long tradition of freethinkers who used the religious vocabulary familiar to the majority.

Coda: Post 9/11, “God Bless America” has turned the 7th inning stretch at baseball games into a religious observance. Fans are now required to stand up and sing Berlin’s 1938 song, often followed by John Denver’s 1974 song “Thank God I’m a Country Boy.” This is regrettable for two reasons: Not only does the show of public piety makes atheist nonparticipants conspicuous, but God is as relevant to baseball as Santa Claus is to the Olympic luge competition. Indeed, the observance trivializes the faith it purports to celebrate – continuing an unfortunate tradition of conflating religion with patriotism.

Other birthdays and events this week—

May 6: American actor, film director and political activist, George Clooney was born (1961).

May 7: Victorian English poet and playwright Robert Browning was born (1812).

May 11: American theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate, Richard P. Feynman was born (1918).

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in my blog, FreethoughtAlmanac.com.