This Week in Freethought History (April 21-27)

Here’s your Week in Freethought History: This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

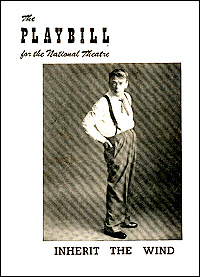

Last Sunday, April 21, but in 1955, Inherit the Wind, a play by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee dramatizing the famous Scopes “Monkey Trial” of the summer of 1925, opened at the National Theatre on Broadway. Inherit the Wind was not about a clash between two 1920s pop stars, Clarence Darrow vs. William Jennings Bryan, or a clash of cultures, intellectual vs. religious. The playwrights are really focused on defending freedom of thought in a time of anti-communist hysteria: The 1950s were a time of cultural anxiety and anti-intellectualism in the U.S., inspired by the crusade of Sen. Joseph McCarthy and his colleagues on the House Un-American Activities Committee. So Drummond (the Darrow character) says to the jury, “Yes there is something holy to me! The power of the individual human mind. An idea is a greater monument than a cathedral. And the advance of man’s knowledge is more of a miracle than any sticks turned to snakes, or the parting of waters. … Gentlemen, progress has never been a bargain. You’ve got to pay for it. … Darwin moved us forward to a hilltop, where we could look back and see the way from which we came. But for this view, this insight, this knowledge, we must abandon our faith in the pleasant poetry of Genesis.”

Last Sunday, April 21, but in 1955, Inherit the Wind, a play by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee dramatizing the famous Scopes “Monkey Trial” of the summer of 1925, opened at the National Theatre on Broadway. Inherit the Wind was not about a clash between two 1920s pop stars, Clarence Darrow vs. William Jennings Bryan, or a clash of cultures, intellectual vs. religious. The playwrights are really focused on defending freedom of thought in a time of anti-communist hysteria: The 1950s were a time of cultural anxiety and anti-intellectualism in the U.S., inspired by the crusade of Sen. Joseph McCarthy and his colleagues on the House Un-American Activities Committee. So Drummond (the Darrow character) says to the jury, “Yes there is something holy to me! The power of the individual human mind. An idea is a greater monument than a cathedral. And the advance of man’s knowledge is more of a miracle than any sticks turned to snakes, or the parting of waters. … Gentlemen, progress has never been a bargain. You’ve got to pay for it. … Darwin moved us forward to a hilltop, where we could look back and see the way from which we came. But for this view, this insight, this knowledge, we must abandon our faith in the pleasant poetry of Genesis.”

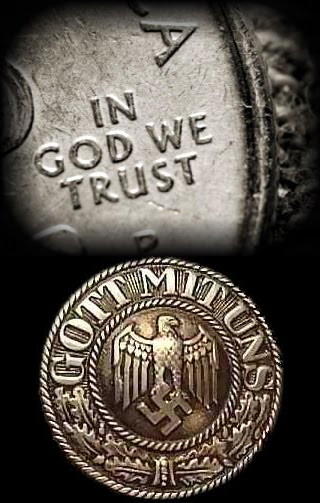

Last Monday, April 22, but in 1864, the U.S. Congress passed an act requiring coins, for the first time since the nation was founded, to include a recognition of God. Replacing the Latin motto, E Pluribus Unum – “Out of many, one” – was one that everyone could read, if not subscribe to: “In God We Trust.” How did this happen? A Rev. Watkinson urged replacing the Goddess of Liberty with a religious slogan on U.S. coinage, writing to Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, “You are probably a Christian” … “Would not the antiquaries of succeeding centuries rightly reason from our past that we were a heathen nation?” A religious slogan, wrote the cleric, “would relieve us from the ignominy of heathenism. This would place us openly under the Divine protection we have personally claimed.” And even though the motto was conceived by a cleric, recommended for its religious purpose, and adopted precisely to acknowledge the Judeo-Christian God, several federal courts have since ruled that “In God We Trust” on our coins – and, since 1954, our currency, is not a religious phrase! What’s troubling is that Nazi Germany had a very similar motto: Gott mit uns (“God with us”). We can suppose the Nazis, too, have been spared the “ignominy of heathenism”!

Last Monday, April 22, but in 1864, the U.S. Congress passed an act requiring coins, for the first time since the nation was founded, to include a recognition of God. Replacing the Latin motto, E Pluribus Unum – “Out of many, one” – was one that everyone could read, if not subscribe to: “In God We Trust.” How did this happen? A Rev. Watkinson urged replacing the Goddess of Liberty with a religious slogan on U.S. coinage, writing to Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, “You are probably a Christian” … “Would not the antiquaries of succeeding centuries rightly reason from our past that we were a heathen nation?” A religious slogan, wrote the cleric, “would relieve us from the ignominy of heathenism. This would place us openly under the Divine protection we have personally claimed.” And even though the motto was conceived by a cleric, recommended for its religious purpose, and adopted precisely to acknowledge the Judeo-Christian God, several federal courts have since ruled that “In God We Trust” on our coins – and, since 1954, our currency, is not a religious phrase! What’s troubling is that Nazi Germany had a very similar motto: Gott mit uns (“God with us”). We can suppose the Nazis, too, have been spared the “ignominy of heathenism”!

Last Tuesday, April 23, but in 1564, the greatest poet and playwright in the English language, William Shakespeare, was baptized, so this is taken as his birthday. Shakespeare is known to be the author of about 38 plays, 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and several other poems. Because few records of Shakespeare’s private life survive, scholars have freely speculated about his religious beliefs. Whereas some scholars suggest The Bard may have been an atheist, and even the Catholic Encyclopedia wonders if “Shakespeare was not infected with the atheism, which was rampant in the more cultured society of the Elizabethan age,” all we can say with certainty is that, in a time when it was a serious offense to be an unfaithful Christian and to skip church services, William Shakespeare said some things no true Christian should have said and failed to do some things that a true Christian should have done.

Last Tuesday, April 23, but in 1564, the greatest poet and playwright in the English language, William Shakespeare, was baptized, so this is taken as his birthday. Shakespeare is known to be the author of about 38 plays, 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and several other poems. Because few records of Shakespeare’s private life survive, scholars have freely speculated about his religious beliefs. Whereas some scholars suggest The Bard may have been an atheist, and even the Catholic Encyclopedia wonders if “Shakespeare was not infected with the atheism, which was rampant in the more cultured society of the Elizabethan age,” all we can say with certainty is that, in a time when it was a serious offense to be an unfaithful Christian and to skip church services, William Shakespeare said some things no true Christian should have said and failed to do some things that a true Christian should have done.

Last Wednesday, April 24, but in 1800, the world’s largest library, the Library of Congress, was founded. The Library’s current collection of 147 million items includes materials in 460 languages, including books, maps, monographs, dissertations, periodicals, voice and music recordings, and 14 million images. The Library of Congress is the largest library ever to exist. The collection and recording of the sum of human knowledge for the betterment of humankind was not a high priority in the Ages of Faith in Christian Europe, or for most of the history of the Muslim East. The idea of human progress was a secular humanist achievement. It is therefore dishonest to crow about the great libraries of the Middle Ages, and the romantic fiction of the monks preserving the classics, without telling us just how many volumes these great Christian libraries comprised. In the solidly Christian period of 500 to 1300, not a library can be found in all of Europe with more that 2,000 volumes, many of them copies of the same title. In the greatest abbey of the 13th century, the Abbey of St. Gall, not a single monk could read!

Last Wednesday, April 24, but in 1800, the world’s largest library, the Library of Congress, was founded. The Library’s current collection of 147 million items includes materials in 460 languages, including books, maps, monographs, dissertations, periodicals, voice and music recordings, and 14 million images. The Library of Congress is the largest library ever to exist. The collection and recording of the sum of human knowledge for the betterment of humankind was not a high priority in the Ages of Faith in Christian Europe, or for most of the history of the Muslim East. The idea of human progress was a secular humanist achievement. It is therefore dishonest to crow about the great libraries of the Middle Ages, and the romantic fiction of the monks preserving the classics, without telling us just how many volumes these great Christian libraries comprised. In the solidly Christian period of 500 to 1300, not a library can be found in all of Europe with more that 2,000 volumes, many of them copies of the same title. In the greatest abbey of the 13th century, the Abbey of St. Gall, not a single monk could read!

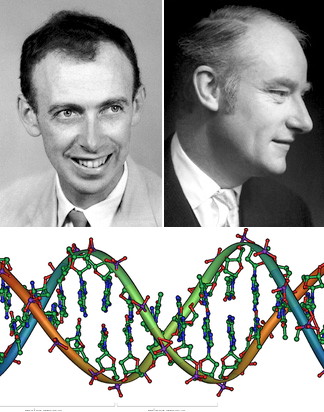

Last Thursday, April 25, but in 1953, an article in Nature magazine, describing the structure of DNA in terms of the now-familiar double helix, was published under the authorship of James D. Watson and Francis Crick. True scientists both, they characterized their discovery as a scientific theory, meaning that their explanation is not only subject to independent verification, but also innately falsifiable. Both won the Nobel Prize in 1962. Francis Crick published a book, The Astonishing Hypothesis (1994), in which he states, “The Astonishing Hypothesis is that You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.” In 1996, Richard Dawkins interviewed James Watson for a film broadcast by the BBC and asked if Watson knew many scientists with strong religious convictions. “Virtually none,” said Watson. “Occasionally, I meet them and I’m a bit embarrassed because I can’t believe that anyone accepts truth by revelation.”

Last Thursday, April 25, but in 1953, an article in Nature magazine, describing the structure of DNA in terms of the now-familiar double helix, was published under the authorship of James D. Watson and Francis Crick. True scientists both, they characterized their discovery as a scientific theory, meaning that their explanation is not only subject to independent verification, but also innately falsifiable. Both won the Nobel Prize in 1962. Francis Crick published a book, The Astonishing Hypothesis (1994), in which he states, “The Astonishing Hypothesis is that You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.” In 1996, Richard Dawkins interviewed James Watson for a film broadcast by the BBC and asked if Watson knew many scientists with strong religious convictions. “Virtually none,” said Watson. “Occasionally, I meet them and I’m a bit embarrassed because I can’t believe that anyone accepts truth by revelation.”

Yesterday, April 26, but in 1837, English physiologist and neurologist Henry Charlton Bastian was born. He graduated at the University of London in 1861 and was professor of the Principles and Practice of Medicine at London University 1867-87 and Censor of the Royal College of Physicians. Bastian was admitted as a Fellow of Royal Society in 1868. To the end of his life he was a champion of spontaneous generation (abiogenesis) of living organisms out of dead material – even defending it against Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch and John Tyndall – and he was the last believer in the scientific world. Bastian was an aggressive materialist. This can be seen in his Brain as the Organ of Mind (1880) and other publications in clinical neurology wherein he takes a materialist view of the causes of paralysis and aphasia. In his notice in the Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography (2008), Edwin Clarke summarizes, “Of Bastian’s industry, tenacity, logic, and experimental versatility—although perhaps misplaced—there can be no question.”

Yesterday, April 26, but in 1837, English physiologist and neurologist Henry Charlton Bastian was born. He graduated at the University of London in 1861 and was professor of the Principles and Practice of Medicine at London University 1867-87 and Censor of the Royal College of Physicians. Bastian was admitted as a Fellow of Royal Society in 1868. To the end of his life he was a champion of spontaneous generation (abiogenesis) of living organisms out of dead material – even defending it against Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch and John Tyndall – and he was the last believer in the scientific world. Bastian was an aggressive materialist. This can be seen in his Brain as the Organ of Mind (1880) and other publications in clinical neurology wherein he takes a materialist view of the causes of paralysis and aphasia. In his notice in the Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography (2008), Edwin Clarke summarizes, “Of Bastian’s industry, tenacity, logic, and experimental versatility—although perhaps misplaced—there can be no question.”

Today, April 27, but in 1822, the 18th President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant, was born. At the close of the American Civil War, the commanding general of the U.S. armies was the most popular man in the country. He was elected president and served two terms, from 1869-1877. However, his administration was marred by a tolerance of corruption, so that he left office as unpopular as he was popular when first elected. Grant was not a member of any church. He was, however, a staunch defender of church-state separation. In a speech in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1875, he unequivocally supported public schools over religious schools, saying, “Encourage free schools, and resolve that not one dollar of money be appropriated to the support of any sectarian school… Leave the matter of religion to the family altar, the Church, and the private schools, supported entirely by private contributions. KEEP CHURCH AND STATE FOREVER SEPARATE.”

Today, April 27, but in 1822, the 18th President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant, was born. At the close of the American Civil War, the commanding general of the U.S. armies was the most popular man in the country. He was elected president and served two terms, from 1869-1877. However, his administration was marred by a tolerance of corruption, so that he left office as unpopular as he was popular when first elected. Grant was not a member of any church. He was, however, a staunch defender of church-state separation. In a speech in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1875, he unequivocally supported public schools over religious schools, saying, “Encourage free schools, and resolve that not one dollar of money be appropriated to the support of any sectarian school… Leave the matter of religion to the family altar, the Church, and the private schools, supported entirely by private contributions. KEEP CHURCH AND STATE FOREVER SEPARATE.”

Also today, April 27, but in 1759, English feminist and radical Mary Wollstonecraft was born. She was largely self-educated and an unusual student, with the radical idea that women should be educated on a par with men. An early feminist, Wollstonecraft found she had a talent for writing, and publishers to promote her, so she published her theories in Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1786). She continued to argue that the rights of men and the rights of women were the same rights. This culminated in her Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, the seminal document in the history of modern feminism. Wollstonecraft associated with a radical intellectual group including Thomas Paine and William Godwin. She married Godwin and, in 1797, died of complications ten days after she gave birth to the future author of the classic novel Frankenstein.

Also today, April 27, but in 1759, English feminist and radical Mary Wollstonecraft was born. She was largely self-educated and an unusual student, with the radical idea that women should be educated on a par with men. An early feminist, Wollstonecraft found she had a talent for writing, and publishers to promote her, so she published her theories in Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1786). She continued to argue that the rights of men and the rights of women were the same rights. This culminated in her Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, the seminal document in the history of modern feminism. Wollstonecraft associated with a radical intellectual group including Thomas Paine and William Godwin. She married Godwin and, in 1797, died of complications ten days after she gave birth to the future author of the classic novel Frankenstein.

Other birthdays and events this week—

April 22: American actor, film director, producer, and writer Jack Nicholson (1937).

April 22: German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724).

April 23: German theoretical physicist and Nobel Laureate, who originated quantum theory, Max Planck (1858).

April 23: British Romantic landscape painter J. M. W. Turner (1775).

April 26: French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix (1798).

April 26: 16th Roman Emperor, from 161 to 180, Marcus Aurelius (121 CE).

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in my blog, FreethoughtAlmanac.com.