This Week in Freethought History (February 3-9)

Here’s your Week in Freethought History: This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

Last Sunday, February 3, but in 1943, aboard a sinking US Army Transport during WWII, helped soldiers board lifeboats and gave up their own life jackets when the supply ran out, thereby sacrificing their lives to save the lives of others. In fact, the sinking of the Dorchester, in which the Four Chaplains and 670 other men died, if it proves anything, proves that nothing fails like prayer. You see, if the actions of the Four Chaplains was a great moral lesson in selflessness for the survivors to witness, it must be admitted that it was hard lesson on those who perished. That God had to drown 674 US soldiers in icy water to give us this heart-warming story, proves not the love of Jehovah, but his malevolence. God could not protect the Four Chaplains, or the sailors who died. God could not even prevent the German U-boat from torpedoing an Army transport. Until that day, these four “religious” heroes did nothing practically useful for America, except to die in place of, perhaps, four sailors, on a doomed ship. The Four Chaplains did what any human being of upright character would do for a fellow human being, religion or no. And that’s just the point: there was no God in their gallantry, no Jesus in their generosity, and in their courage no creed.

Last Sunday, February 3, but in 1943, aboard a sinking US Army Transport during WWII, helped soldiers board lifeboats and gave up their own life jackets when the supply ran out, thereby sacrificing their lives to save the lives of others. In fact, the sinking of the Dorchester, in which the Four Chaplains and 670 other men died, if it proves anything, proves that nothing fails like prayer. You see, if the actions of the Four Chaplains was a great moral lesson in selflessness for the survivors to witness, it must be admitted that it was hard lesson on those who perished. That God had to drown 674 US soldiers in icy water to give us this heart-warming story, proves not the love of Jehovah, but his malevolence. God could not protect the Four Chaplains, or the sailors who died. God could not even prevent the German U-boat from torpedoing an Army transport. Until that day, these four “religious” heroes did nothing practically useful for America, except to die in place of, perhaps, four sailors, on a doomed ship. The Four Chaplains did what any human being of upright character would do for a fellow human being, religion or no. And that’s just the point: there was no God in their gallantry, no Jesus in their generosity, and in their courage no creed.

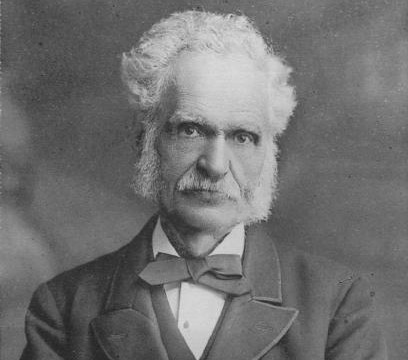

Last Monday, February 4, but in 1842, Danish critic and scholar Georg Brandes was born. Brought up in a Jewish middle-class family of non-orthodox leanings, as Brandes recalled, “Neither of my parents was in any way associated with the Jewish religion, and neither of them ever went to the Synagogue.” Over the course of his 85 years, Brandes exercised great influence on Scandinavian and European literature, but moved around the world rather often. One of the reasons was his freethinking philosophy: his views forced him to leave Denmark for Berlin, but in 1883 he was persuaded to return to Denmark. Both he and his brother were outspoken agnostics. A friend and correspondent with Friedrich Nietzsche, Brandes once wrote, “It would be as impossible for me to attack Christianity as it would be impossible for me to attack werewolves.” His last years were dedicated to anti-religious polemics and a rejection of what he saw as the hypocrisy of prudish sexuality. “But my doubt would not be overcome,” wrote Brandes. “Kierkegaard had declared that it was only to the consciousness of sin that Christianity was not horror or madness. For me it was sometimes both.”

Last Monday, February 4, but in 1842, Danish critic and scholar Georg Brandes was born. Brought up in a Jewish middle-class family of non-orthodox leanings, as Brandes recalled, “Neither of my parents was in any way associated with the Jewish religion, and neither of them ever went to the Synagogue.” Over the course of his 85 years, Brandes exercised great influence on Scandinavian and European literature, but moved around the world rather often. One of the reasons was his freethinking philosophy: his views forced him to leave Denmark for Berlin, but in 1883 he was persuaded to return to Denmark. Both he and his brother were outspoken agnostics. A friend and correspondent with Friedrich Nietzsche, Brandes once wrote, “It would be as impossible for me to attack Christianity as it would be impossible for me to attack werewolves.” His last years were dedicated to anti-religious polemics and a rejection of what he saw as the hypocrisy of prudish sexuality. “But my doubt would not be overcome,” wrote Brandes. “Kierkegaard had declared that it was only to the consciousness of sin that Christianity was not horror or madness. For me it was sometimes both.”

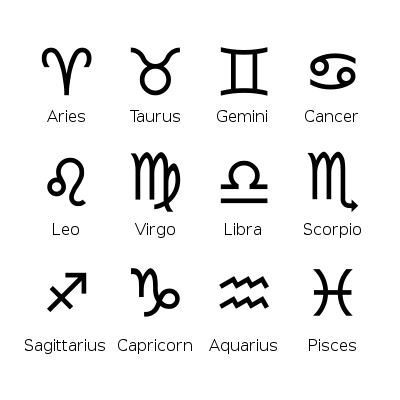

Last Tuesday, February 5, but in 1962, the Great Aquarian Conjunction took place; that is, the sun, the moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn were in conjunction as viewed from Earth – not in a straight line, but only within 16 degrees of each other. They were joined by a solar eclipse. Astrologers predicted dire and fantastic things that, of course, never took place. This should not be surprising: the pseudoscience of astrology rarely gets it right – and astrology is no better than statistical chance for predicting the future. No matter how powerful a coincidence, there is no necessary causation behind astrology. It has never been demonstrated that being born on the same date affects your fate. Astrology is actually out of sync with the stars as they can be seen today, 1800 years after Ptolemy codified the practice. Astrology is based on your time of birth, but if there is any planetary influence at all, shouldn’t it be at your conception? Despite the lack of a causative mechanism – how, exactly, does astrology work? – astrology is believed by millions. Why? People turn to astrology, as they turn to religion, because they feel overwhelmed by the size, power and complexity of the universe. But if you really want to see the future, to avoid disaster (literally, “bad stars”), we should look not to the stars or to planetary conjunctions: we should look to ourselves.

Last Tuesday, February 5, but in 1962, the Great Aquarian Conjunction took place; that is, the sun, the moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn were in conjunction as viewed from Earth – not in a straight line, but only within 16 degrees of each other. They were joined by a solar eclipse. Astrologers predicted dire and fantastic things that, of course, never took place. This should not be surprising: the pseudoscience of astrology rarely gets it right – and astrology is no better than statistical chance for predicting the future. No matter how powerful a coincidence, there is no necessary causation behind astrology. It has never been demonstrated that being born on the same date affects your fate. Astrology is actually out of sync with the stars as they can be seen today, 1800 years after Ptolemy codified the practice. Astrology is based on your time of birth, but if there is any planetary influence at all, shouldn’t it be at your conception? Despite the lack of a causative mechanism – how, exactly, does astrology work? – astrology is believed by millions. Why? People turn to astrology, as they turn to religion, because they feel overwhelmed by the size, power and complexity of the universe. But if you really want to see the future, to avoid disaster (literally, “bad stars”), we should look not to the stars or to planetary conjunctions: we should look to ourselves.

Last Wednesday, February 6, but in 1564, British poet and playwright Christopher Marlowe was born. Rejecting a clerical career, Marlowe moved to London and began a six-year career as a dramatist, producing the two parts of Tamburlaine the Great, Dr. Faustus (in which appear the famous lines, “Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships, And burnt the topless towers of Ilium? Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss!), The Jew of Malta (in which appears the line, “I count religion but a childish toy, and hold there is no sin but ignorance”), and Edward II. He was arguably the most talented playwright in England next to William Shakespeare, who was born in the same year, and had he lived beyond age 29 he might have equaled or even surpassed the Bard. In Elizabethan England, skepticism was still a crime that could be punished severely. Marlowe, Walter Raleigh and others formed a private circle of Rationalists, which clerical critics called “Raleigh’s school of Atheism.” It is asserted by some scholars that Marlowe’s death by violence in Eleanor Bull’s tavern on 30 May 1593 was not a simple dispute over a bill that accelerated under the fuel of drink. It is possible that he was murdered for political reasons: A week before his death, the Privy Council had ordered Marlowe’s arrest on charges of Atheism, blasphemy, subversion and homosexuality.

Last Wednesday, February 6, but in 1564, British poet and playwright Christopher Marlowe was born. Rejecting a clerical career, Marlowe moved to London and began a six-year career as a dramatist, producing the two parts of Tamburlaine the Great, Dr. Faustus (in which appear the famous lines, “Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships, And burnt the topless towers of Ilium? Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss!), The Jew of Malta (in which appears the line, “I count religion but a childish toy, and hold there is no sin but ignorance”), and Edward II. He was arguably the most talented playwright in England next to William Shakespeare, who was born in the same year, and had he lived beyond age 29 he might have equaled or even surpassed the Bard. In Elizabethan England, skepticism was still a crime that could be punished severely. Marlowe, Walter Raleigh and others formed a private circle of Rationalists, which clerical critics called “Raleigh’s school of Atheism.” It is asserted by some scholars that Marlowe’s death by violence in Eleanor Bull’s tavern on 30 May 1593 was not a simple dispute over a bill that accelerated under the fuel of drink. It is possible that he was murdered for political reasons: A week before his death, the Privy Council had ordered Marlowe’s arrest on charges of Atheism, blasphemy, subversion and homosexuality.

Last Thursday, February 7, but in 1812, the greatest novelist in the English language, Charles Dickens was born in Landport, Hampshire, England. Dickens was an acclaimed author by the time he made his first American tour – where his novels were shamelessly pirated for the stage – and he returned to publish American Notes (1842) and invented the modern idea of Christmas with A Christmas Carol (1843). All of Dickens’ novels are characterized by attacks on social evils, injustice, and hypocrisy. While he was devout in his own way, Dickens typifies the romantic regard for religion coupled with a disdain for its theology. To his friend and first biographer, John Forster, Dickens wrote, “I have a sad misgiving that the religion of Ireland lies as deep at the root of all its sorrows, even as English misgovernment and Tory villainy.” Edgar Johnson, his chief modern biographer, wrote, “Inclining toward Unitarianism, he had little respect for mystical religious dogma. He hated the Roman Catholic Church, ‘that curse upon the world,’ as the tool and coadjutor of oppression throughout Europe. … He had rejected the Church of England and detested the influence of its bishops in English politics.” Dickens ridiculed evangelicals in Dombey and Son, for example, and wrote Sunday Under Three Heads against an Act of Parliament proposing to outlaw Sunday recreation for the working class. Yet Dickens prayed often, included a declaration of Christian belief in his will, and recommended his relatives follow the morality of Jesus. It was for biographer Hesketh Pearson to explain: “His attitude to the religious beliefs of his time was as independent as his attitude to the political faiths. He accepted the teachings of Christ, not the doctrines of the Christian churches… .”

Last Thursday, February 7, but in 1812, the greatest novelist in the English language, Charles Dickens was born in Landport, Hampshire, England. Dickens was an acclaimed author by the time he made his first American tour – where his novels were shamelessly pirated for the stage – and he returned to publish American Notes (1842) and invented the modern idea of Christmas with A Christmas Carol (1843). All of Dickens’ novels are characterized by attacks on social evils, injustice, and hypocrisy. While he was devout in his own way, Dickens typifies the romantic regard for religion coupled with a disdain for its theology. To his friend and first biographer, John Forster, Dickens wrote, “I have a sad misgiving that the religion of Ireland lies as deep at the root of all its sorrows, even as English misgovernment and Tory villainy.” Edgar Johnson, his chief modern biographer, wrote, “Inclining toward Unitarianism, he had little respect for mystical religious dogma. He hated the Roman Catholic Church, ‘that curse upon the world,’ as the tool and coadjutor of oppression throughout Europe. … He had rejected the Church of England and detested the influence of its bishops in English politics.” Dickens ridiculed evangelicals in Dombey and Son, for example, and wrote Sunday Under Three Heads against an Act of Parliament proposing to outlaw Sunday recreation for the working class. Yet Dickens prayed often, included a declaration of Christian belief in his will, and recommended his relatives follow the morality of Jesus. It was for biographer Hesketh Pearson to explain: “His attitude to the religious beliefs of his time was as independent as his attitude to the political faiths. He accepted the teachings of Christ, not the doctrines of the Christian churches… .”

Yesterday, February 8, but in 1825, British naturalist and explorer Henry Walter Bates was born. He travelled with rainforests of the Amazon with Alfred Russel Wallace 1848-50. He then left Wallace and explored the Amazon for nine more years, bringing home 8,000 new species, mostly insects, for scientific study. He returned to England in the same year that Darwin’s Origin of Species was published. Bates was one of a group of supporters of evolutionary theory, which included Darwin, Wallace, J.D. Hooker, Fritz Müller, Richard Spruce and Thomas Henry Huxley. In his work with the Amazonian butterfly, he described what came to be known as “Batesian mimicry” – a form of mimicry in which a harmless species has evolved to imitate the warning signals of a harmful species directed at a common predator (paper read before the Linnaean Society in 1861). His book, The Naturalist on the Amazons (1863), brought him fame and praise from Darwin. He was assistant secretary of the Royal Geographical Society for 27 years, until his death in 1892. Although not explicit in his own works, and described elsewhere as a Unitarian, that Bates was an outspoken agnostic is recorded in Edward Clodd’s Memoir (1916).

Yesterday, February 8, but in 1825, British naturalist and explorer Henry Walter Bates was born. He travelled with rainforests of the Amazon with Alfred Russel Wallace 1848-50. He then left Wallace and explored the Amazon for nine more years, bringing home 8,000 new species, mostly insects, for scientific study. He returned to England in the same year that Darwin’s Origin of Species was published. Bates was one of a group of supporters of evolutionary theory, which included Darwin, Wallace, J.D. Hooker, Fritz Müller, Richard Spruce and Thomas Henry Huxley. In his work with the Amazonian butterfly, he described what came to be known as “Batesian mimicry” – a form of mimicry in which a harmless species has evolved to imitate the warning signals of a harmful species directed at a common predator (paper read before the Linnaean Society in 1861). His book, The Naturalist on the Amazons (1863), brought him fame and praise from Darwin. He was assistant secretary of the Royal Geographical Society for 27 years, until his death in 1892. Although not explicit in his own works, and described elsewhere as a Unitarian, that Bates was an outspoken agnostic is recorded in Edward Clodd’s Memoir (1916).

Today, February 9, but in 1893, the first public strip-tease took place. Mona, an artist’s model, thought she had more than just the prettiest legs, and, to prove it, jumped nude onto a table for the art students. She may have been unaware that she was making history: She got a 100-franc fine from the police and a riot in protest from her student fans. The Moulin Rouge, which had opened just a few years before, picked up on the idea… and strip-tease was born. With the triumph of sky-god religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – the ascetic idea developed that things of the earth were unclean. And that was especially true of the sexual power of women over men. Still, the idea that women are too deafened by the din of their bodies to hear God’s word* was fully espoused by the Church Fathers. The flesh was the enemy of the spirit. Genesis 1:31 was gainsaid by Matthew 5:28: “anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart.” But in strip-tease, the amount of control over their bodies and their sexuality is in the hands of the women, where it belongs. The question of exploitation doesn’t come out in the way it is popularly assumed. Even lap-dancers, the modern upshot for the private audience of the nude excitation of a public audience, can earn $1500 to $3700 per week. Who is being exploited: the well-paid dancer or the gullible client?

Today, February 9, but in 1893, the first public strip-tease took place. Mona, an artist’s model, thought she had more than just the prettiest legs, and, to prove it, jumped nude onto a table for the art students. She may have been unaware that she was making history: She got a 100-franc fine from the police and a riot in protest from her student fans. The Moulin Rouge, which had opened just a few years before, picked up on the idea… and strip-tease was born. With the triumph of sky-god religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – the ascetic idea developed that things of the earth were unclean. And that was especially true of the sexual power of women over men. Still, the idea that women are too deafened by the din of their bodies to hear God’s word* was fully espoused by the Church Fathers. The flesh was the enemy of the spirit. Genesis 1:31 was gainsaid by Matthew 5:28: “anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart.” But in strip-tease, the amount of control over their bodies and their sexuality is in the hands of the women, where it belongs. The question of exploitation doesn’t come out in the way it is popularly assumed. Even lap-dancers, the modern upshot for the private audience of the nude excitation of a public audience, can earn $1500 to $3700 per week. Who is being exploited: the well-paid dancer or the gullible client?

*[Paraphrased from the 1994 film Sirens, written and directed by John Duigan.]

Other birthdays this week—

February 5: Scottish anatomist and physical anthropologist Sir Arthur Keith was born (1866).

February 5: English engineer and prolific inventor Sir Hiram Maxim was born (1840).

February 7: Nobel-winning American novelist Sinclair Lewis was born (1885).

February 8: English author and art critic John Ruskin was born (1819).

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in my blog, FreethoughtAlmanac.com.