The Week in Freethought History (December 30-January 5)

Here’s your Week in Freethought History: This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

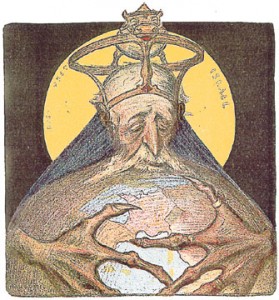

Last Sunday, December 30, but in 1993, the Jew-killers agreed to make peace with the Christ-killers – that is, the Vatican and Israel agreed to recognize each other. This diplomatic nicety did not, of course, end anti-Semitism anymore than the establishment of the State of Israel did, but it is at least gratifying to see two major superstitions agree to play nice with each other on the world stage. That one party (the Roman Church, headquartered at the Vatican) was the offender, and the other (the world’s Jews, with a homeland on appropriated real estate called Israel) was the “offendee,” did not detract from the salutary effect on the Church’s reputation. Jewish history under Christian monarchs had been one of almost unbroken persecution, savage treatment (for refusing to become Christian), the occasional blood libel, and frequent expulsions. This ill treatment was ostensibly because the Roman Church taught that the Jews were to be hated for killing their god, Christ – as if killing a god were possible. But blaming Jews for killing Christ is hypocritical: without the death of their Christ, there would be no Christianity! In fact, European Christianity used hatred of Jews as an organizing force from the earliest times. The Fundamental Agreement Between the Holy See and the State of Israel, signed on this date in 1993, came over 50 years too late for the Holocaust, and 45 years after the establishment of the State of Israel. And it also bears some theological complications. The Roman Church had been teaching for so long that God hates Jews – so… if God is right today, and Jews are not “reviled of God,” was He wrong in the Dark Age, when faith was stronger?

Last Sunday, December 30, but in 1993, the Jew-killers agreed to make peace with the Christ-killers – that is, the Vatican and Israel agreed to recognize each other. This diplomatic nicety did not, of course, end anti-Semitism anymore than the establishment of the State of Israel did, but it is at least gratifying to see two major superstitions agree to play nice with each other on the world stage. That one party (the Roman Church, headquartered at the Vatican) was the offender, and the other (the world’s Jews, with a homeland on appropriated real estate called Israel) was the “offendee,” did not detract from the salutary effect on the Church’s reputation. Jewish history under Christian monarchs had been one of almost unbroken persecution, savage treatment (for refusing to become Christian), the occasional blood libel, and frequent expulsions. This ill treatment was ostensibly because the Roman Church taught that the Jews were to be hated for killing their god, Christ – as if killing a god were possible. But blaming Jews for killing Christ is hypocritical: without the death of their Christ, there would be no Christianity! In fact, European Christianity used hatred of Jews as an organizing force from the earliest times. The Fundamental Agreement Between the Holy See and the State of Israel, signed on this date in 1993, came over 50 years too late for the Holocaust, and 45 years after the establishment of the State of Israel. And it also bears some theological complications. The Roman Church had been teaching for so long that God hates Jews – so… if God is right today, and Jews are not “reviled of God,” was He wrong in the Dark Age, when faith was stronger?

Last Monday, December 31, but in 1514, Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius was born. Vesalius was the son of the court-apothecary to the Emperor Charles V and studied medicine in the tradition of the ancient Roman anatomist Galen (129-211), but in acquiring great skill in dissection, he discovered many errors in Galen’s work. When Vesalius was only 28, he published the greatest work on human anatomy yet seen De Humani Corporis Fabrica, which influenced the understanding of human anatomy up to the 19th century. It is with some irony that Vesalius is claimed by the Catholic Encyclopedia and is considered one of the great Catholic scientists. Even that reference admits, “Personally he avoided expressing his opinion, in order not to fall under suspicion of heresy,” which is as if to say that Vesalius might have been a freethinker if the price of professing it were not his life! In fact, Vesalius was harassed by the Church all his life, and only as physician to Emperor Charles V was he protected from the Inquisition. The cause of this clerical hostility is a further irony: the famous anatomist was hounded for his practice of human dissection! Human dissection was considered forbidden by the Roman Church since Tertullian and Augustine. What irked the Church was perhaps not so much that Vesalius dissected human bodies, but that when he did so he did not find this highly venerated if highly speculative “resurrection bone.” Furthermore, as the legend of Adam and Eve demonstrates, there must be one less rib in male humans than in females. This, too, Vesalius found erroneous. Finally, the charge of dissecting a living man was trumped up – the man’s family also charged Vesalius with Atheism – and the Inquisition moved against the greatest surgeon in Europe. The price of protecting Vesalius from the pope’s ecclesiastical enforcers was a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He reached Jerusalem, but never made it back home, dying at age 49 in Zakinthos, Greece, on 15 October 1564. You could say Andreas Vesalius died for the church that persecuted him.

Last Tuesday, January 1, but in 1854, British anthropologist and folklorist Sir James George Frazer was born. In 1890, Frazer published, in two volumes, the book for which he is remembered today, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. The Golden Bough, named after the golden bough in the sacred grove at Nemi, near Rome, shows the parallels between Christianity and the rites and superstitions of earlier cultures – the unspoken conclusion being that the borrower was Christianity. However, the only statements of Frazer’s approaching religious skepticism in The Golden Bough are in the 1900 edition. There, Frazer admits that his work “strikes at the foundations of beliefs in which the hopes and aspirations of humanity through long ages have sought a refuge.” Frazer’s biographer, R.A. Downie, does not discuss his religious beliefs. The Dean of the Chapel of Trinity College, although giving him a religious funeral, said after Frazer’s death, “He was not an Atheist. I would say perhaps that he held his judgment in suspense.” That is the common definition of an Agnostic.

Last Wednesday, January 2, but in 1920, American science and science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov was born. He was educated in Orthodox Judaism, but religion had little influence throughout Asimov’s childhood. Asimov studied chemistry at Columbia University, New York, where he graduated in 1939, eceived his M.A. in 1941, and in 1948, earned a Ph.D. in biochemistry. He lectured from 1955 to 1958 at Boston University School of Medicine, but his first love was writing. It was as a science writer, but most famously as a science-fiction writer, that Asimov, for works such as the Foundation Trilogy and I, Robot, became one of a triumvirate of S‑F immortals that included Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008) and Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988). Asimov turned out 470 books in four decades of writing, and on a dizzying array of topics, including Shakespeare, Gilbert and Sullivan, literature, technology, world history, mythology – and four memoirs. In one of these he noted, “I have never, in all my life, not for one moment, been tempted toward religion of any kind. The fact is that I feel no spiritual void. I have my philosophy of life, which does not include any aspect of the supernatural.” The American Humanist Association named Asimov Humanist of the Year in 1984 and later voted him its president. In The Roving Mind, Asimov wrote, “Don’t you believe in flying saucers? they ask me. Don’t you believe in telepathy? – in ancient astronauts? – in the Bermuda Triangle? – in life after death? No, I reply. No, no, no, no, and again no.” Only toward the end of his life was Asimov comfortable in admitting his atheism. “Since I am an atheist,” he said in his final memoir, “and do not believe that either God or Satan, Heaven or Hell, exists, I can only suppose that when I die, there will only be an eternity of nothingness to follow.” “Life is pleasant” wrote Asimov, “Death is peaceful. It’s the transition that’s troublesome.”

Last Thursday, January 3, but in 106 BCE, Roman statesman and orator Marcus Tullius Cicero was born. Having chosen parents not among the ruling class in oligarchic Rome, Cicero rose through the political ranks – quaestor, aedile, praetor, and consul – much as one would today: after distinguishing himself as a lawyer. At the peak of his political career, as Consul, in 63 BCE, Cicero exposed the Catiline conspiracy to overthrow Rome. Cicero was not only an idealist in morals but an advanced skeptic toward religion. In his rejection of the Roman (pagan) religion, he was followed by many of the educated in Roman society. He declined to join in the First Triumvirate, which gave Cicero’s enemies an opening to apply an ex post facto law to get him exiled. Banned from politics even after his return from exile in 47 BCE, Cicero had much time to reflect on philosophy. His treatise On the Nature of the Gods gives the arguments for and against the existence of God, but he takes neither side. After the collapse of the First Triumvirate, the crossing of the Rubicon, the civil war, and the murder of Julius Caesar (44 BCE), Cicero made the wrong enemies by bitterly attacking Marc Antony in speeches he called Philippics. The Second Triumvirate agreed on a power-sharing plan and Marc Antony took revenge by ordering the orator’s assassination. Belatedly attempting to flee Rome, Cicero was murdered on 7 December 43 BCE. By Antony’s order, Cicero’s head and his hands were cut off and nailed to the speaker’s podium in the Senate as a warning to others.

Yesterday, January 4, but in 1884, the longest-lived, continuously operating Socialist organization, the Fabian Society, was founded in London. Founders Frank Podmore and Edward Pease envisioned a society opposed to the revolutionary theory of Marxism, holding instead that social reforms and Socialistic public policy can be instituted through “permeation”: that is, through Socialist public policy writing and election of Fabian-supported Members of Parliament – in effect, using the system to change the system. The Fabians were appropriately named for the Roman general Quintus Fabius (ca. 280-203 BCE), known as Cunctator from his strategy of delaying battle until the right moment, thereby weakening the opposition without resorting to pitched battle. The Fabians achieved recognition with the publication of Fabian Essays, beginning in 1889 with a tract on poverty – Why Are the Many Poor?, which came out in the wake of the 1888 Match Girls’ Strike – and by employing some rather talented writers. Some of the better-known Fabians include atheist-turned Theosophist Annie Besant, the virulently anti-Christian dramatist George Bernard Shaw, the Atheist and novelist H.G. Wells, the Rationalist and statesman Harry Snell, and the Agnostic poet who died before his time, Rupert Brooke – which, you can see from the links to the Freethought Almanac were Freethinkers.

Today, January 5, but in 1527, Swiss Anabaptist reformer Felix Manz was drowned in punishment for preaching adult baptism. as opposed to the infant baptism most Protestant sects approved. That he was drowned for punishment in the Limmat, near the current Rathaus bridge in Zürich, seems somehow to make one superstition superior to another based on the police power of the one who holds it. Manz was a co-founder of the original Swiss Brethren Anabaptist congregation in Zürich, Switzerland. The term “Anabaptist” was coined by their detractors and means Protestants who are “baptized again.” By all accounts, Felix Manz was well educated in Hebrew, Greek, and Latin and became a follower of Hulrich Zwingli (see below). But Manz began questioning the mass, the nature of church and state connections, and infant baptism, eventually breaking with Zwingli over this. Manz formed the first church of the Radical Reformation and the movement spread rapidly, although he was arrested and imprisoned on a number of occasions between 1525 and 1527. On 7 March 1526, an edict of the Zürich council made adult baptism punishable by drowning. The 29-year-old Manz was arrested. He protested that he wanted only “to bring together those who were willing to accept Christ, obey the Word, and follow in His footsteps, to unite with these by baptism, and to leave the rest in their present conviction.” But Zwingli and the council were unpersuaded. That and the little-known fact that the Anabaptists were semi-Rationalistic, which is always heretical, and many followers of Manz rejected the Trinity and developed advanced (for the time) ideas of social reform. Manz’s death made him the first Protestant in history to be martyred at the hands of other Protestants. Catholics, of course, were quick to exterminate Anabaptists wherever they could find them.

Other birthdays and events this week—

January 1: Swiss Protestant reformer Huldrych Zwingli was born.

January 3: Belgian archaeologist and philologist Franz Cumont was born.

January 5: Italian philologist and writer, author of The Name of the Rose (1983), Umberto Eco was born.

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in my blog, FreethoughtAlmanac.com.