The Week in Freethought History (October 14-20)

Here’s your Week in Freethought History: This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

Last Sunday, October 14, but in 1950, Unification Church founder Sun Myung Moon (문선명) was liberated by UN Forces from Hung Nam prison in Korea, where he had been incarcerated for espionage. He was 30 years old. Four years later, Moon founded the church whose followers are disparagingly but accurately called "Moonies" – as all of Moon's followers believe Moon is the second coming of Jesus, the Messiah. Moon wrote his beliefs into a book, Divine Principle (1956), about the principle of the unification of mind and body. According to Moon, control of one's eating, sleeping and sexual desire leads to salvation. Denying these three things, of course, makes minds easier to control, so the Moonies have often been charged with being a mind-control cult. Like most fundamentalists, Moonies despise the separation of church and state. And, like many millennialist Christians, Moonies hope for a Third World War, after which the world's faiths will be unified and religion and government become one. This is at odds with American tradition and government, but many otherwise sensible conservatives supported him.

Last Sunday, October 14, but in 1950, Unification Church founder Sun Myung Moon (문선명) was liberated by UN Forces from Hung Nam prison in Korea, where he had been incarcerated for espionage. He was 30 years old. Four years later, Moon founded the church whose followers are disparagingly but accurately called "Moonies" – as all of Moon's followers believe Moon is the second coming of Jesus, the Messiah. Moon wrote his beliefs into a book, Divine Principle (1956), about the principle of the unification of mind and body. According to Moon, control of one's eating, sleeping and sexual desire leads to salvation. Denying these three things, of course, makes minds easier to control, so the Moonies have often been charged with being a mind-control cult. Like most fundamentalists, Moonies despise the separation of church and state. And, like many millennialist Christians, Moonies hope for a Third World War, after which the world's faiths will be unified and religion and government become one. This is at odds with American tradition and government, but many otherwise sensible conservatives supported him.

Last Monday, October 15, but in 1917, American historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. was born. The son of a prominent American historian of the same name, Arthur Junior graduated from Harvard University in 1938, and became a professor of history at Harvard from 1946 to 1961. He was speech writer for President John F. Kennedy, and later became Professor of Humanities of the City University of New York. Among his many histories and popular writings are The Age of Jackson (1945), which won a Pulitzer Prize for history and A Thousand Days (1965), a Pulitzer Prize-winning history of the Kennedy Administration. In a 1989 speech, Schlesinger mused, “As a historian, I confess to a certain amusement when I hear the Judeo-Christian tradition praised as the source for our present-day concern for human rights.... In fact, the great religious ages were notable for their indifference to human rights... Human rights is not a religious idea. It is a secular idea, the product of the last four centuries of Western history.... The basic human rights documents – the American Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man – were written by political, not religious, leaders.”

Last Monday, October 15, but in 1917, American historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. was born. The son of a prominent American historian of the same name, Arthur Junior graduated from Harvard University in 1938, and became a professor of history at Harvard from 1946 to 1961. He was speech writer for President John F. Kennedy, and later became Professor of Humanities of the City University of New York. Among his many histories and popular writings are The Age of Jackson (1945), which won a Pulitzer Prize for history and A Thousand Days (1965), a Pulitzer Prize-winning history of the Kennedy Administration. In a 1989 speech, Schlesinger mused, “As a historian, I confess to a certain amusement when I hear the Judeo-Christian tradition praised as the source for our present-day concern for human rights.... In fact, the great religious ages were notable for their indifference to human rights... Human rights is not a religious idea. It is a secular idea, the product of the last four centuries of Western history.... The basic human rights documents – the American Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man – were written by political, not religious, leaders.”

Also last Monday, October 15, but in 1844, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was born. Brought up by pious relatives, Nietzsche was educated at the universities of Bonn (1864-65) and Leipzig (1864-68), becoming a professor at the University of Basel, Switzerland, at the age of 25. He soon rejected the faith of his father and became a lifelong critic of Christianity. In his most famous work, Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1892), he writes, “God is a thought that makes crooked all that is straight.... Jesus died too soon. He would have repudiated his doctrine if he had lived to my age.” And in The Twilight of the Gods he wrote, “I call Christianity the one great curse, the one enormous and innermost perversion, the one great instinct of revenge, for which no means are too venomous, too underhand, too underground and too petty — I call it the one immortal blemish of mankind.... The only excuse for God is that he doesn't exist.” Friedrich Nietzsche was an Atheist. Nietzsche's idea of the Übermensch or “higher man” (sometimes translated as “Superman”), which he conceived as a dynamic, perceptive person, was reinterpreted by the Nazis as the “master race” – a concept Nietzsche would have renounced like his friendship with composer Richard Wagner: He was neither anti-Semitic, nor a militarist, nor even a nationalist, as he renounced his Prussian citizenship in 1869!

Also last Monday, October 15, but in 1844, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was born. Brought up by pious relatives, Nietzsche was educated at the universities of Bonn (1864-65) and Leipzig (1864-68), becoming a professor at the University of Basel, Switzerland, at the age of 25. He soon rejected the faith of his father and became a lifelong critic of Christianity. In his most famous work, Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1892), he writes, “God is a thought that makes crooked all that is straight.... Jesus died too soon. He would have repudiated his doctrine if he had lived to my age.” And in The Twilight of the Gods he wrote, “I call Christianity the one great curse, the one enormous and innermost perversion, the one great instinct of revenge, for which no means are too venomous, too underhand, too underground and too petty — I call it the one immortal blemish of mankind.... The only excuse for God is that he doesn't exist.” Friedrich Nietzsche was an Atheist. Nietzsche's idea of the Übermensch or “higher man” (sometimes translated as “Superman”), which he conceived as a dynamic, perceptive person, was reinterpreted by the Nazis as the “master race” – a concept Nietzsche would have renounced like his friendship with composer Richard Wagner: He was neither anti-Semitic, nor a militarist, nor even a nationalist, as he renounced his Prussian citizenship in 1869!

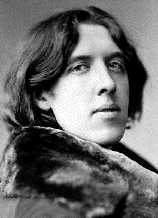

Last Tuesday, October 16, but in 1854, Irish writer Oscar Wilde was born. Wilde probably inherited from his feminist mother, by example if not by genetics, a flair for the dramatic: He adopted a personal style of outrageous dress – created by theater costumiers rather than tailors – and behaved just as flamboyantly. Wilde viewed all religions “as colleges in a great university,” but was attracted to Catholicism, to which he never converted, as “the greatest and most romantic of them.” From 1888-1895, Wilde wrote most of his important works: a semi-autobiographical novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), and five plays: Salomé (1892), Lady Windermere's Fan (1893), A Woman of No Importance (1893), An Ideal Husband (1895), and what is considered his masterpiece of farce, The Importance of Being Earnest (1895). Wilde admired Jesus on the aesthetic level, but was skeptical of Christianity: “A thing is not necessarily true because a man dies for it,” he said. About the Bible, Wilde mused sadly, “When I think of all the harm that book has done, I despair of ever writing anything to equal it.” Asked once by Lord Balfour to describe his religion, Oscar Wilde replied, “Well, you know, I don't think I have any. I am an Irish Protestant.”

Last Tuesday, October 16, but in 1854, Irish writer Oscar Wilde was born. Wilde probably inherited from his feminist mother, by example if not by genetics, a flair for the dramatic: He adopted a personal style of outrageous dress – created by theater costumiers rather than tailors – and behaved just as flamboyantly. Wilde viewed all religions “as colleges in a great university,” but was attracted to Catholicism, to which he never converted, as “the greatest and most romantic of them.” From 1888-1895, Wilde wrote most of his important works: a semi-autobiographical novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), and five plays: Salomé (1892), Lady Windermere's Fan (1893), A Woman of No Importance (1893), An Ideal Husband (1895), and what is considered his masterpiece of farce, The Importance of Being Earnest (1895). Wilde admired Jesus on the aesthetic level, but was skeptical of Christianity: “A thing is not necessarily true because a man dies for it,” he said. About the Bible, Wilde mused sadly, “When I think of all the harm that book has done, I despair of ever writing anything to equal it.” Asked once by Lord Balfour to describe his religion, Oscar Wilde replied, “Well, you know, I don't think I have any. I am an Irish Protestant.”

Last Wednesday, October 17, 1260, that one of the finest examples of high Gothic art, Chartres Cathedral in northern France, was consecrated under King (Saint) Louis and Pope Alexander IV. It is known officially as Le Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres. Surely, the Chartres Cathedral is an example of the quality of art inspired by religious faith? Such a romantic notion of the Middle Ages, as often taught in high school history classes, would be true if it could be demonstrated from history that periods of undisturbed religious faith coincided with periods of great art. Even a casual observer of the period would note that of course there was great religious art in the medieval era because the Roman Catholic Church was very wealthy and therefore employed the most talented artists! It must have started with the architects, but what do we really know about them? For example, the architect of the beautiful Speyer Cathedral in Germany was the Bishop of Osnabruck. He took religious orders only for the title and revenues and was described by contemporaries as "sensual and worldly." The architect at Chartres was Béranger, but little is known of his religious faith, or if he had any at all. In fact, the Chartres Cathedral was constructed as a tourist trap: its very purpose was to attract pilgrims to patronize local merchants and fill church coffers with cash. Civic authorities candidly crowed that they just wanted to outshine, if not outspend, other cities. Was this religious passion, or the desire for donations? The most authoritative histories of the era confirm that the artwork was inspired by an economic revival and a concentration of wealth, not a religious revival or a concentration on Christ. Does religion inspire great art? If the Cathedral at Chartres is any example, the answer is – only when the inspiration comes in the form of gold coins!

Last Wednesday, October 17, 1260, that one of the finest examples of high Gothic art, Chartres Cathedral in northern France, was consecrated under King (Saint) Louis and Pope Alexander IV. It is known officially as Le Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres. Surely, the Chartres Cathedral is an example of the quality of art inspired by religious faith? Such a romantic notion of the Middle Ages, as often taught in high school history classes, would be true if it could be demonstrated from history that periods of undisturbed religious faith coincided with periods of great art. Even a casual observer of the period would note that of course there was great religious art in the medieval era because the Roman Catholic Church was very wealthy and therefore employed the most talented artists! It must have started with the architects, but what do we really know about them? For example, the architect of the beautiful Speyer Cathedral in Germany was the Bishop of Osnabruck. He took religious orders only for the title and revenues and was described by contemporaries as "sensual and worldly." The architect at Chartres was Béranger, but little is known of his religious faith, or if he had any at all. In fact, the Chartres Cathedral was constructed as a tourist trap: its very purpose was to attract pilgrims to patronize local merchants and fill church coffers with cash. Civic authorities candidly crowed that they just wanted to outshine, if not outspend, other cities. Was this religious passion, or the desire for donations? The most authoritative histories of the era confirm that the artwork was inspired by an economic revival and a concentration of wealth, not a religious revival or a concentration on Christ. Does religion inspire great art? If the Cathedral at Chartres is any example, the answer is – only when the inspiration comes in the form of gold coins!

Last Thursday, October 18, but in 1927, American actor George C. Scott, winner of four Oscar nominations, was born. Generally considered an actor's actor, Scott created memorable characters in Anatomy of a Murder (1959) and The Hustler (1961), for which he won his first two Oscar nominations, then Dr. Strangelove (1964), and finally Patton (1970). It was for Patton that Scott won, but refused, the Best Actor Oscar. Shortly before his death on 22 September 1999, during an interview on the TV news magazine “60 Minutes,” Scott said he did not believe in God at all.

Last Thursday, October 18, but in 1927, American actor George C. Scott, winner of four Oscar nominations, was born. Generally considered an actor's actor, Scott created memorable characters in Anatomy of a Murder (1959) and The Hustler (1961), for which he won his first two Oscar nominations, then Dr. Strangelove (1964), and finally Patton (1970). It was for Patton that Scott won, but refused, the Best Actor Oscar. Shortly before his death on 22 September 1999, during an interview on the TV news magazine “60 Minutes,” Scott said he did not believe in God at all.

Also last Thursday, October 18, but in 1859, French philosopher Henri-Louis Bergson was born. At age 18, he won a prize for solving a mathematical problem, and another for his scientific work in 1877. Bergson was influenced early on by the writings of Herbert Spencer, John Stuart Mill, and Charles Darwin. His three principal works were Time and Free Will (1889), Matter and Memory (1896), and Creative Evolution (1907). It was in this latter work that Bergson answered William Paley's argument from design for the existence of God – that if a watch requires a watchmaker, then a world requires a world-maker: “In short, intelligence, considered in what seems to be its original feature, is the faculty of manufacturing artificial objects, especially tools to make tools, and of indefinitely urging the manufacture.” In other words, rather than jumping from “watch implies watch-maker, therefore world implies world-maker,” Bergson argued that intelligence can be inferred only from the making of artificial objects, not natural objects. But it was in this same Creative Evolution in which Bergson worked out his theory that a Vital Impulse – élan vital – or soul of the universe, guides and controls evolution. Bergson's élan vital he was pleased to call God, but not in the personal, prayerful sense in which most Christians understand the concept. Indeed, he rejected the personal God of theology, saying, “he is nothing, since he does nothing.”

Also last Thursday, October 18, but in 1859, French philosopher Henri-Louis Bergson was born. At age 18, he won a prize for solving a mathematical problem, and another for his scientific work in 1877. Bergson was influenced early on by the writings of Herbert Spencer, John Stuart Mill, and Charles Darwin. His three principal works were Time and Free Will (1889), Matter and Memory (1896), and Creative Evolution (1907). It was in this latter work that Bergson answered William Paley's argument from design for the existence of God – that if a watch requires a watchmaker, then a world requires a world-maker: “In short, intelligence, considered in what seems to be its original feature, is the faculty of manufacturing artificial objects, especially tools to make tools, and of indefinitely urging the manufacture.” In other words, rather than jumping from “watch implies watch-maker, therefore world implies world-maker,” Bergson argued that intelligence can be inferred only from the making of artificial objects, not natural objects. But it was in this same Creative Evolution in which Bergson worked out his theory that a Vital Impulse – élan vital – or soul of the universe, guides and controls evolution. Bergson's élan vital he was pleased to call God, but not in the personal, prayerful sense in which most Christians understand the concept. Indeed, he rejected the personal God of theology, saying, “he is nothing, since he does nothing.”

Yesterday, Friday, October 19, but in 1784, English writer James Leigh Hunt was born. Early on, Hunt developed a twin passion for poetry and politics and befriended other young poets who favored political reform, including Thomas Barnes, Henry Brougham, Lord Byron, William Hazlitt, Charles Lamb and Percy Bysshe Shelley. In 1822, Hunt traveled to Italy with Byron and Shelley and created a radical political journal called The Liberal, but without the danger that got him arrested in England. There were only four editions, but the first included writings from William Hazlitt and Mary Shelley. Leigh Hunt was a Deist, and strongly opposed Christianity, as evidenced in his Religion of the Heart. It has been suggested that Leigh Hunt was the model for Harold Skimpole in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, but Dickens denied this. Indeed, Dickens described Hunt as “the very soul of honour and truth.”

Yesterday, Friday, October 19, but in 1784, English writer James Leigh Hunt was born. Early on, Hunt developed a twin passion for poetry and politics and befriended other young poets who favored political reform, including Thomas Barnes, Henry Brougham, Lord Byron, William Hazlitt, Charles Lamb and Percy Bysshe Shelley. In 1822, Hunt traveled to Italy with Byron and Shelley and created a radical political journal called The Liberal, but without the danger that got him arrested in England. There were only four editions, but the first included writings from William Hazlitt and Mary Shelley. Leigh Hunt was a Deist, and strongly opposed Christianity, as evidenced in his Religion of the Heart. It has been suggested that Leigh Hunt was the model for Harold Skimpole in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, but Dickens denied this. Indeed, Dickens described Hunt as “the very soul of honour and truth.”

Also yesterday, Friday, October 19, but in 1605, British writer Sir Thomas Browne was born. While supported by his medical practice, he published on a wide variety of topics, including religion and science. His Religio Medici, written in English, ran through at least eight editions while he was alive. It was translated into most European languages in his day, and is often described as a fine piece of religious literature, but it was put on the Roman Catholic Index of Prohibited Books, all the same. Although usually taken to be a Christian, Browne was a Deist and a skeptic regarding immortality. It was Browne who said, "As for those wingy mysteries in divinity, and airy subtleties in religion, which have unhinged the brains of better heads, they never stretched the pia mater of mine.”

Also yesterday, Friday, October 19, but in 1605, British writer Sir Thomas Browne was born. While supported by his medical practice, he published on a wide variety of topics, including religion and science. His Religio Medici, written in English, ran through at least eight editions while he was alive. It was translated into most European languages in his day, and is often described as a fine piece of religious literature, but it was put on the Roman Catholic Index of Prohibited Books, all the same. Although usually taken to be a Christian, Browne was a Deist and a skeptic regarding immortality. It was Browne who said, "As for those wingy mysteries in divinity, and airy subtleties in religion, which have unhinged the brains of better heads, they never stretched the pia mater of mine.”

Today, October 20, but in 1859, American philosopher and educator John Dewey was born. Taking his degree in philosophy from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Dewey gradually shed the strictures of his strict religious upbringing. His philosophical naturalism understood human thought as practical problem-solving which proceeds by testing rival hypotheses against experience in order to achieve the “warranted assertability” from which correct action derives. This included social reform. As Dewey said, “Demons were once appealed to in order to explain bodily disease, and no such thing as a strictly natural death was supposed to happen. The importation of general moral causes to explain present social phenomena is on the same intellectual level. Reinforced by the prestige of traditional religions, and backed by the emotional force of beliefs in the supernatural, it stifles the growth of ... social intelligence.” It was John Dewey who said, “There is nothing left worth preserving in the notions of unseen powers, controlling human destiny, to which obedience and worship are due.”

Today, October 20, but in 1859, American philosopher and educator John Dewey was born. Taking his degree in philosophy from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Dewey gradually shed the strictures of his strict religious upbringing. His philosophical naturalism understood human thought as practical problem-solving which proceeds by testing rival hypotheses against experience in order to achieve the “warranted assertability” from which correct action derives. This included social reform. As Dewey said, “Demons were once appealed to in order to explain bodily disease, and no such thing as a strictly natural death was supposed to happen. The importation of general moral causes to explain present social phenomena is on the same intellectual level. Reinforced by the prestige of traditional religions, and backed by the emotional force of beliefs in the supernatural, it stifles the growth of ... social intelligence.” It was John Dewey who said, “There is nothing left worth preserving in the notions of unseen powers, controlling human destiny, to which obedience and worship are due.”

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in my blog, FreethoughtAlmanac.com.