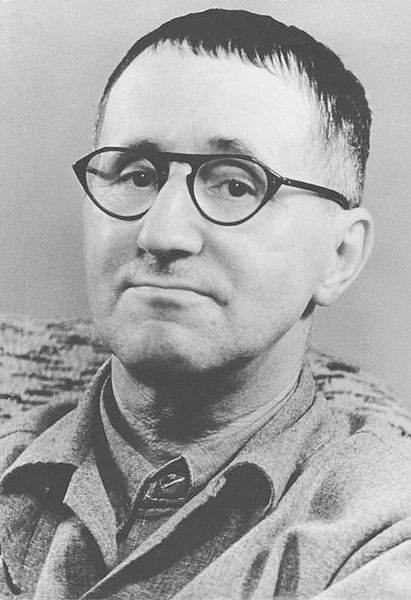

February 10: Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht (1898)

It was on this date, February 10, 1898, that German dramatist Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht was born in Augsburg, Bavaria, the product of a Catholic father and a Protestant mother. Bertolt Brecht studied medicine and worked as a hospital orderly for a time in World War I. Being attracted to Socialism and to theater — and (contradicting Shakespeare), believing "Art is not a mirror held up to reality, but a hammer with which to shape it" — Brecht combined the two and became a leading reformer on the 20th century stage.

Brecht wrote in his Diaries, "The church is a circus for the masses,"* and believed organized religion had been standing in the way of progress for centuries. In his plays, such as The Bible (1914), Brecht took a dim view of narrow-minded religion. Brecht also noted what he considered a corrupt alliance between religion and capitalism in Brecht's 1928 Berlin hit, The Threepenny Opera (Die Dreigroschenoper).

Biographer Karl H. Schoeps says Brecht was accused of attacking Christianity in Saint Joan of the Stockyards (Die Heilige Johanna der Schlachthöfe, 1929-30), but "he wanted only to expose one characteristic commonly displayed by so-called Christians and Christian organizations: the readiness to talk about God and goodness but a reluctance to remedy the injustices of the daily life around them."** The Nazis balked at allowing Saint Joan's production for that reason, and due to its leftist point of view.

The play in which Brecht had the greatest opportunity to criticize organized religion, The Life of Galileo (Leben des Galilei, 1938-39) — written while Brecht was in exile from Nazi Germany. Brecht claimed Galileo was not meant to insult the Church: indeed, in his play, Brecht took it easy on the church officials who persecuted the great scientist. But in The Good Woman of Setzuan (Der Gute Mench von Sezuan, 1938-39), the role of the three gods was a clear satire on religionists, who give commandments but no practical advice. The gods also symbolized philanthropists who give money but won't work for human betterment.

Brecht's clearest shot at religion was in Act II of his opera — with long-time collaborator Kurt Weill — The Rise and Fall of the City Mahagonny (Aufstieg und Fall der Städt Mahagonny, 1929). Mahagonny has been described as the opposite of a Passion Play. In it, Brecht writes,

During a grey morning, in the midst of whiskey

God came to Mahagonny,

God came to Mahagonny.

In the midst of whiskey,

We noticed God in Mahagonny.

"Do you swill like sponges,

my good wheat year after year?

No one did expect my coming!

When I come now is everything prepared?"...

"All of you down to Hell!

Put your Virginia cigars in your bags!

Off to you to My Hell you rascals!

In to black Hell with all of you rabble!"

Look upon God did the men of Mahagonny.

"NO!", said the men of Mahagonny.

* Diaries 1920-1922, published 1975; quoted in Schoeps. ** Karl H. Schoeps, Bertolt Brecht, 1977.

Quote from Bertolt Brecht—

"What they could do with round here is a good war. What else can you expect with peace running wild all over the place? You know what the trouble with peace is? No organization."

— Mother Courage and Her Children (Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder, 1939)

Originally published February 2004 by Ronald Bruce Meyer.