The Necessity of Socialism

Imagine, if you will, an economic system in which 99% of the people make 50% of the money and 1% of the people own the other 50% of the money. Imagine further that the share of the 1% keeps increasing because they control so much of the economy that they can buy the legislators, subvert regulation by buying the courts, and provide most of the money necessary to elect a chief executive who promises to perpetuate their wealth. Imagine further still that the wealth acquired by the 1% is allowed to be passed down from generation to generation, snowballing to immense proportions over the years. Imagine now that you are in the bottom 99% of this economic system. Would that sound to you like a fair or a just or even a stable system?

I’ve been reading a commentary by evangelical Christian and capitalist apologist Cal Thomas, one entitled “Why Socialism appeals to young voters.” Right off the bat, the editor who assigned the title betrays an ignorance of the demographics of socialism’s appeal. But leave it to Mr. Thomas himself to betray an ignorance of what socialism is in fact, rather than what it is in his febrile imagination.

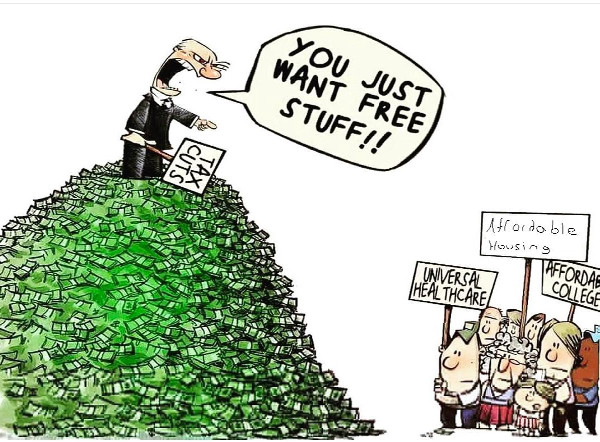

His first argument, that socialists say it isn’t fair that some people make more money than others, is a straw man: no socialist makes such an argument. What socialists actually say is that vast disparities of wealth distort democracy by allowing a small minority to make the policies and the rules under which the majority, with little or no input, must live. That’s what is not fair – in a democracy.

His first argument, that socialists say it isn’t fair that some people make more money than others, is a straw man: no socialist makes such an argument. What socialists actually say is that vast disparities of wealth distort democracy by allowing a small minority to make the policies and the rules under which the majority, with little or no input, must live. That’s what is not fair – in a democracy.

Then Mr. Thomas goes on to conflate liberalism and socialism, so that he can assign “failures” to socialism that are more properly failures of liberalism. Apparently, his history reaches back only to LBJ’s “Great Society,” not the New Deal of FDR, under which an economy in Depression was injected with the cash and the employment needed to save capitalism from its worst failure. But FDR’s greater achievement was to save the USA from a violent revolution, because the capitalists of the time would not share a fair portion of the wealth created by the working class and the working class had had enough of it.

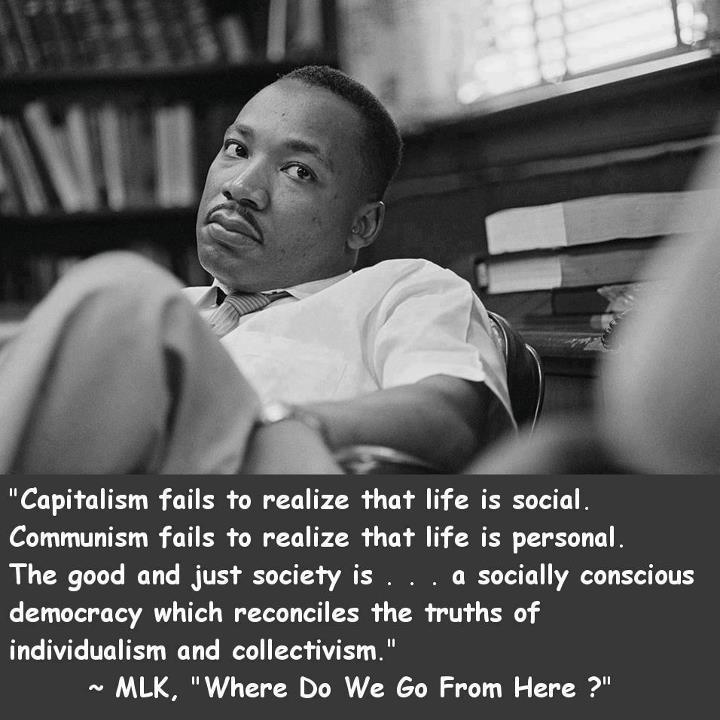

When government has to do what capitalism will not, or cannot, that’s socialism. Another way of putting it, in today’s terms and under today’s tax system (where the burden is increasingly shifted to the shrinking middle class), is that socialism gives taxpayers their money’s worth.

Mr. Thomas’s next argument follows the lead of a critic of the Great Society he cites: that employers like McDonald’s and Starbucks are leading the explosion in job creation. Really? Low-wage employment may be good for the stats, but what matters is not that you are employed, but that you make enough money through your employment to sustain a family. That’s just not happening.

Furthermore, McDonald’s and Starbucks are leading the explosion in automation, which is causing a collapse in employment. Where does all the surplus labor go? Capitalism fails to answer.

Mr. Thomas goes on to praise “markets” for their salutary effect on economic prosperity. But markets are a human creation, not a law of nature, and must not be conflated with capitalism. Markets are merely mechanisms of distribution: under slavery, there were markets; even under feudalism, goods and services were distributed via markets.

Mr. Thomas goes on to praise “markets” for their salutary effect on economic prosperity. But markets are a human creation, not a law of nature, and must not be conflated with capitalism. Markets are merely mechanisms of distribution: under slavery, there were markets; even under feudalism, goods and services were distributed via markets.

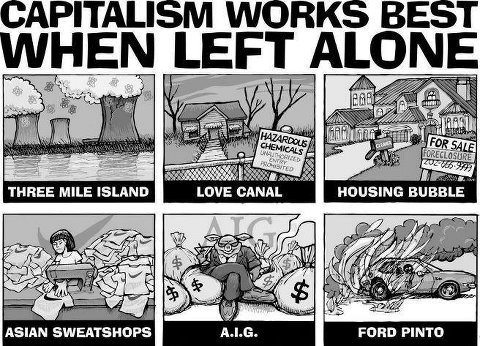

Mr. Thomas blames socialism for certain failures, but fails to cite specific examples. He even goes so far as to cite both bias in education, and a failure to remember history, for most Americans not acknowledging this supposedly self-evident truth. But determining that an economic system is a success or a failure depends on how you measure it. Under capitalism, we are experiencing a level of income inequality in the USA not seen in 100 years. Would you call that a success of capitalism?

The most famous examples of socialism that right-wing critics like to cite are the Soviet Union and Communist China. But if they can be measured by economic growth, the USA took almost 170 years to transform from an agrarian backwater into an economic superpower. On the other hand, from 1917 until its conversion to crony capitalism in 1989, it took only 70 years for the Soviet Union to achieve a similar transformation; from the communist revolution in 1949 to the present day, it took China a mere 70 years to become the number two world economic power. To say flatly that socialism in Russia and China has failed is not accurate.

But there are significant failures of capitalism, chiefly its failure to end poverty. Indeed, the system has resisted every effort to mitigate poverty. Capitalists have vigorously opposed minimum wages, living wages (by moving jobs offshore or replacing workers with machines) and increasing pensions. Capitalists have also opposed unemployment insurance, Social Security, and Medicare. One might conclude from this that poverty is not a “bug” but a feature in capitalism. Did capitalism even lessen poverty? Arguing that capitalism made poverty less severe is like arguing that slavery made the lives of slaves better.

But there are significant failures of capitalism, chiefly its failure to end poverty. Indeed, the system has resisted every effort to mitigate poverty. Capitalists have vigorously opposed minimum wages, living wages (by moving jobs offshore or replacing workers with machines) and increasing pensions. Capitalists have also opposed unemployment insurance, Social Security, and Medicare. One might conclude from this that poverty is not a “bug” but a feature in capitalism. Did capitalism even lessen poverty? Arguing that capitalism made poverty less severe is like arguing that slavery made the lives of slaves better.

More significantly, capitalism is an enemy of democracy. Concentrated wealth has a way of distorting the politics of a nation. Capitalists are traditionally uncomfortable with democracy: too much public participation is not good for the bottom line. And as for capitalism’s treatment of organized workers, somebody should probably tell the rich that workers banding together peacefully to present formal grievances is the alternative we worked out a long time ago to breaking down the factory owner’s front door and beating him to death in front of his family. I feel like they forget. Having no democracy in the workplace makes it easier to subvert democracy in society.

I should also point out that capitalism is socially divisive. Nothing serves corporate profits better than to see black, white and brown workers scramble in desperation for scraps, forgetting they have more in common with each other than they do with their capitalist masters. And consider this: it was the capitalist focus on profits over people that cost my brother his job at a major corporation. And, just to be clear, it wasn’t a Muslim, or a black person, or a gay person, or a woman, who fired him. My sense is that it was a straight, Christian white guy in a suit.

And if we really want to get into “How do you pay for it all?” socialists should respond with: “The same way you pay for endless wars.” It seems there is always money enough for the military (i.e., welfare for capitalist defense contractors), but never money enough for the masses. The bloated US war budget is where the real money is.

And if we really want to get into “How do you pay for it all?” socialists should respond with: “The same way you pay for endless wars.” It seems there is always money enough for the military (i.e., welfare for capitalist defense contractors), but never money enough for the masses. The bloated US war budget is where the real money is.

Socialism is not about taking money from people who work hard and giving it to those who don’t. That describes capitalism – especially when you consider the nearly $2 trillion in tax cuts Mr. Trump gave to corporations and the wealthy in 2018. If Mr. Thomas wants to defend that giveaway, he might want to recall what Jesus thought of the money changers in the temple.

Hi Ron,

Full disclosure: I am your nephew and an aspiring, early automation engineer.

I want to first praise this piece as well-reasoned and argued approach to supporting a combination of democratic rule with social awareness, both pieces clearly lacking in our current government today. This was a great read, and I thank you for posting it.

That said, I invite you to consider speaking of automation as less of an evil or a devil to be fought against and consider the benefits of automation in our society. If the lower level, low paying jobs are automated, then we don't need as many people to fill those jobs, which then leads to fewer jobs overall available for people to be working. Well with automation, you need the people that create the automated process, service the machines where applicable, service the software and provide regular updates, and people to operate the machines or the software beyond the writing of the code. Ideally, automation would take away the mundane and frivolous repetitive tasks and open up additional free time. Time that members of the society may use for leisure and entertainment, either partaking of it or creating it, which leads to a happier overall society.

While the fruits of my labor when creating automation may take the jobs of four entry-level positions, the value of the service I provide is higher than the entry-level position, though generally not paid at the same rate as the four folks out of a job, so a major win for the business. However in most cases, rather than four people being replaced, those four other people wouldn't have been hired anyway, and the slack would be picked up by the current employees, or the work would be missed entirely, and absorbed in a loss or cost of doing business. My point here being not all automation is really replacing an individuals job, but perhaps lightening the load of the current employees and reducing the costs of doing business.

I view automation overall as reducing demand for unskilled labor and providing additional jobs for skilled laborers. Society overall then nets fewer under-employed workers in the workforce and increases business gains (or reducing potential losses on the other side of that coin) to the benefit of all.

Hi, Josh!

Thanks for reading and commenting thoughtfully. I hope your takeaway was not that I think automation is an absolute evil. I consider it more like an inevitability, with some unfortunate side effects. I encourage you to read “The War on Normal People” by presidential candidate and entrepreneur Andrew Yang for some insight and perspective on automation and its effects on employment. His most controversial solution is a form of universal basic income (UBI) which he calls the Freedom Dividend. (He also wears a lapel pin that says “MATH,” which actually stands for “Make America Think Harder”)

To me, as with Mr. Yang, the difficulty caused by automation is what you do with the surplus labor. Yes, retraining is possible, in theory, but I doubt that a coal miner can be retrained as a software coder, for example. Automation gives employers essentially two choices: (1) pay workers the same and give them fewer hours and more leisure (as you seem to suggest), or (2) fire the surplus labor and let society take up the burden. Under capitalism, the choice is almost always (2). What’s not to like about cutting payroll costs and increasing profits?

As an aside, you might consider that if the workplace were democratically run (like a co-op), option (2) would not even be considered – nor would there be offshoring of jobs or polluting of the neighborhood!

Like you, I’m in favor of more leisure and less drudgery, especially for people with kids who value time spent in rearing the next generation. But people have to live. And, without employment, we as a society haven’t yet figured out how to achieve that end without finding somebody willing to pay for it.