June 14: Che Guevara (1928)

It was on this date, June 14, 1928, that Argentine-born Marxist revolutionist, physician and military leader Che Guevara was born Ernesto Guevara (Lynch) in Rosario, Santa Fe, Argentina. He grew up in a family which already had leftist leanings, but which also valued education: Guevara’s reading list not only included Karl Marx but William Faulkner, André Gide, Jules Verne, Jawaharlal Nehru, Franz Kafka, Albert Camus, Vladimir Lenin, Jean-Paul Sartre (with whom he met in 1960), Anatole France, Friedrich Engels, H. G. Wells, and Robert Frost. Years later, the CIA would give him the backhand compliment, “Che is fairly intellectual for a Latino.”

Guevara traveled throughout South America as a medical student (1950-1951) and was horrified to witness the effects of capitalist exploitation there: poverty, hunger, disease and political disenfranchisement. When he tried to assist with social reforms in Guatemala under President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, he witnessed for himself the CIA-assisted overthrow of this democratically elected leader at the bidding of the politically powerful United Fruit Company. Because of that, and his observations of the working conditions of the miners in Anaconda’s Chuquicamata copper mine, and the crushing poverty he saw in remote areas of South America, Guevara was permanently radicalized. Although awarded his medical degree in June 1953, he ultimately gave up medicine for political reform and armed resistance to capitalist abuse.

In 1955, while working in a Mexico City hospital, Guevara was introduced to Cuban revolutionist Fidel Castro, only two years his elder, while associating with a Cuban exile community. Castro easily recruited Guevara into his 26th of July Movement, as both were anti-imperialist. Plans were made to overthrow the corrupt regime of Fulgencio Batista in Cuba. It was a bloody, three-year struggle, during which Che acquired a reputation for ruthlessness and brilliance. During the struggle, Che wrote to his mother (15 July 1956), “I am not Christ or a philanthropist, old lady, I am all the contrary of a Christ.... I fight for the things I believe in, with all the weapons at my disposal and try to leave the other man dead so that I don’t get nailed to a cross or any other place.”* And, elsewhere, Che would say, “In fact, if Christ himself stood in my way, I, like Nietzsche, would not hesitate to squish him like a worm.” Yet, after speaking with Guevara at length in 1962, journalist Marilyn Zeitlin would remark, “There was something Christ-like about him. I really felt that when he was talking to me, he was telling the truth.”**

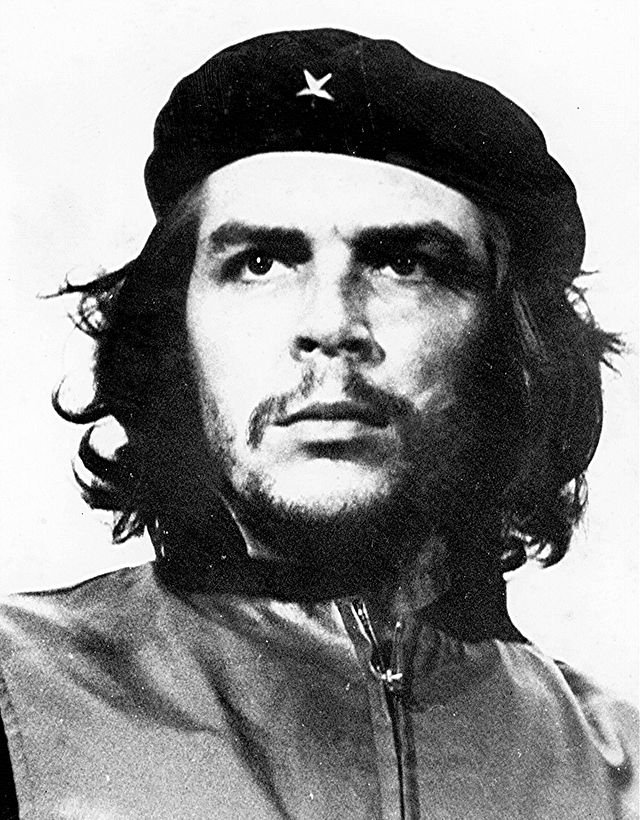

By 1958, the Cuban rebels, led by Che Guevara, had captured the city of Santa Clara. They forced Batista and his corrupt junta—aligned not only with U.S. business interests but with elements of organized crime—to flee Cuba, along with a lot of stolen cash, on 1 January 1959. In that year, Che was named president of the National Bank of Cuba. It is said that in order to show his disdain for money, he signed bills with just his nickname, “Che.” Eighteen months after the success of the Cuban revolution, at a memorial gathering for victims of the munitions freighter La Coubre which blew up in Havana Harbor (and which was widely held to be a CIA plot to disrupt the new Cuban government, and at which scene Che himself gave medical attention to the injured), Cuban photographer Alberto Korda (aka Alberto Diaz Gutierrez) snapped what was to become the most iconic picture of the 20th century. Called Guerrillero Heroico, and captured on 5 March 1960, Korda later remarked its 31-year-old subject’s expression of anger, pain and “absolute implacability.”* After the photographer died, on 25 May 2001, the Maryland Institute College of Art declared this picture of Che Guevara the world’s most famous photograph. It is not surprising, after La Coubre, that Che spoke to the Cuban militia that same year (16 August 1960), saying, “Our enemy, and the enemy of all America, is the monopolistic government of the United States of America.”

Che was not finished with revolutionist activity: in 1964, he left Cuba and as part of a Cuban delegation addressed the United Nations. Although condemning the U.N. for ignoring South African apartheid, in particular, he condemned the U.S. for their hypocritical racial segregation policies, saying “Those who kill their own children and discriminate daily against them because of the color of their skin; those who let the murderers of blacks remain free, protecting them, and furthermore punishing the black population because they demand their legitimate rights as free men—how can those who do this consider themselves guardians of freedom?”† By then, Che had become a “revolutionary statesman of world stature,” traveling to troubled spots around the globe and criticizing the depredations of capitalism. In this, he said,

The laws of capitalism, blind and invisible to the majority, act upon the individual without his thinking about it... The amount of poverty and suffering required for the emergence of a Rockefeller, and the amount of depravity that the accumulation of a fortune of such magnitude entails, are left out of the picture, and it is not always possible to make the people in general see this.††

In 1965, Che lent his support to the ongoing anti-colonialist struggle in the African Congo. By 1966, he was aiding the guerilla movement in Bolivia, where he was hunted down by the U.S.-backed Bolivian army. Although the U.S. wanted Che captured alive for interrogation, the Bolivian president, René Barrientos, ordered him killed—thereby avoiding a messy trial and any further incitement to revolution in Bolivia. Che was executed privately in a rural hut, on 9 October 1967, by a Bolivia soldier with a U.S.-made rifle. His hands were amputated for fingerprint identification and Che’s body was helicoptered away from La Higuera, Vallegrande, Bolivia. Bolivian army officers refused to reveal whether his remains had been buried or cremated, so Che’s body was lost... until it was rediscovered in a mass grave in 1997.

In 2008, a 12-foot bronze statue of Che Guevara was unveiled in the city of his birth. Che remains a national hero in Cuba, where a 5-story steel outline of his face adorns the Ministry of the Interior building, in the Plaza de la Revolución, in Havana, where he once worked. Lionized by liberals, Che is condemned by corporate capitalists for his communist ideology, even while money is made off of his iconic portrait! Che Guevara, a Marxist humanist of no known religion, lived his ideals and, when faced with the assassin’s rifle, he shouted, “Shoot me, you coward! You are only going to kill a man!”*

_____

* Che Guevara in a letter to his mother, 15 July 1956, as quoted in Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life by Jon Lee Anderson (1997).

** Journalist Marilyn Zeitlin, after speaking with Che Guevara for six hours on 12 September 1962, as quoted in Che Guevara: Icon, Myth, and Message by David Kunzle (1997).

† “Colonialism is Doomed.” Speech to the 19th General Assembly of the United Nations in New York City by Cuban representative Che Guevara on 11 December 1964.

†† “Socialism and Man in Cuba.” Letter to Carlos Quijano, editor of Marcha, a weekly newspaper published in Montevideo, Uruguay; published as “From Algiers, for Marcha: The Cuban Revolution Today” by Che Guevara on 12 March 1965.