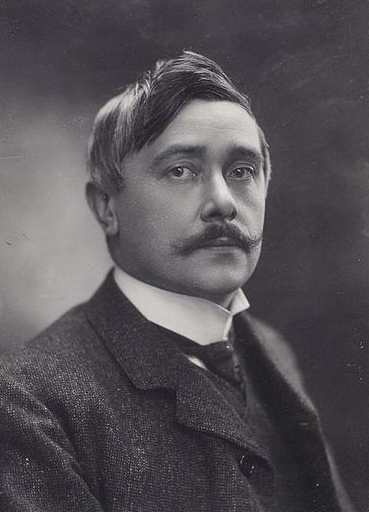

August 29: Maurice Maeterlinck (1862)

It was on this date, August 29, 1862, that Belgian symbolist playwright, poet and Nobel laureate Maurice Maeterlinck was born Maurice Polydore Marie Bernard Maeterlinck in Ghent, Belgium, into a wealthy, French-speaking family. Education under Jesuit control and literary restrictions instilled in Maeterlinck a distaste for the Catholic Church and organized religion generally. “The decent moderation of today will be the least of human things tomorrow. At the time of the Spanish Inquisition, the opinion of good sense and of the good medium was certainly that people ought not to burn too large a number of heretics; extreme and unreasonable opinion obviously demanded that they should burn none at all,” he later wrote (“Our Social Duty” in The Measure of the Hours, 1907). At the urging of his father, he studied law at the University of Ghent and practiced until 1896. By then he had moved to Paris and was gaining enthusiastic praise for Intruder (1890), The Blind (1890) and Pelléas and Mélisande (1892), symbolist plays working the themes of death and the meaning of life from the point of view of fatalism. The latter work inspired an orchestral suite by Gabriel Fauré, an opera by Claude Debussy, a symphonic poem by Arnold Schoenberg and incidental music by Jean Sibelius. Influenced by his relationship with the singer and actress Georgette Leblanc (1895-1918), Maeterlinck began to write female characters more in control of their destinies than was culturally common. The Belgian government awarded him the Triennial Prize for Dramatic Literature in 1903. This was followed by his most famous work, The Blue Bird in 1908.

For his plays and exquisitely written moral essays, Maeterlinck won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1911. By the time he had written La mort (1913) Maeterlinck had rejected the idea of a future life, although he still dabbled in mysticism. In politics, he had become openly socialist – his essay “The Intelligence of Flowers” (1906) had expressed sympathy with socialist ideas – and took the anti-Catholic side during a Belgian trade union strike. “Each progressive spirit is opposed by a thousand mediocre minds appointed to guard the past,” he said (ibid, 1907). For criticizing the Roman Catholic Church, his entire body of work (“opera omnia”) was placed on the Index of Prohibited Books. Maeterlinck was made a count by Albert I, King of the Belgians in 1932, but had to flee Belgium ahead of the rise of the Nazis because, “I knew that if I was captured by the Germans I would be shot at once, since I have always been counted as an enemy of Germany because of my play, Le Bourgmestre de Stillemonde, which dealt with the conditions in Belgium during the German Occupation of 1918.”

Maeterlinck died an unbeliever in Nice on 6 May 1949. There was no priest at his funeral. It was Maurice Maeterlinck who said, “A truth that disheartens, because it is true, is still of far more value than the most stimulating of falsehoods” (Wisdom and Destiny, 1898) and “All our knowledge merely helps us to die a more painful death than the animals that know nothing. A day will come when science will turn upon its error and no longer hesitate to shorten our woes. A day will come when it will dare and act with certainty; when life, grown wiser, will depart silently at its hour, knowing that it has reached its term” (Our Eternity, 1919).