June 28: The “Lemon Test” (1971) and Church-State Separation

It was on this date, June 28, 1971, that the U.S. Supreme Court handed down the most significant ruling to date on the issue of church-state separation, limiting with the “Lemon Test” just how far the states and the United States can go in forcing religious support on citizens. In Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971), the plaintiffs, Alton T. Lemon (et al.), asked the Court to tell David H. Kurtzman, Superintendent of Public Instruction of Pennsylvania (et al.) to stop supplementing the salaries and other expenses of Roman Catholic schools, even when teaching secular subjects in nonpublic schools. In the process of deciding the case, the Supreme Court established the 3-pronged “Lemon test,” which details the requirements for legislation concerning religion, any one prong of which could trigger a violation of church-state separation under the establishment clause of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution:

It was on this date, June 28, 1971, that the U.S. Supreme Court handed down the most significant ruling to date on the issue of church-state separation, limiting with the “Lemon Test” just how far the states and the United States can go in forcing religious support on citizens. In Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971), the plaintiffs, Alton T. Lemon (et al.), asked the Court to tell David H. Kurtzman, Superintendent of Public Instruction of Pennsylvania (et al.) to stop supplementing the salaries and other expenses of Roman Catholic schools, even when teaching secular subjects in nonpublic schools. In the process of deciding the case, the Supreme Court established the 3-pronged “Lemon test,” which details the requirements for legislation concerning religion, any one prong of which could trigger a violation of church-state separation under the establishment clause of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution:

1. The government's action must have a secular legislative purpose;

2. The government's action must have the primary effect of neither advancing or inhibiting religion;

3. The government's action must result in no “excessive government entanglement” with religion.

The Court found, 8-0, that the Pennsylvania and similar laws, which provided 96% of its supplemental funding for salaries and materials to parochial (Catholic) schools, result in “excessive entanglement” between the government and religion. The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment was designed to avoid state “sponsorship, financial support, and active involvement of the sovereign in religious activity.” The “Lemon Test” ensured that the general population’s interests take priority over any particular religious institution.

Detractors of the decision cite its obviously difficult applicability, its “opacity and its malleability,” its “judicial activism” (by which most conservatives mean a decision with which they do not agree), and often make the evidence-free claim that “Lemon” has chilled legitimate religious expression. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, a Roman Catholic and no friend of church-state separation, colorfully described it as like “some ghoul in a late-night horror movie that repeatedly sits up in its grave and shuffles abroad after being repeatedly killed and buried, Lemon stalks our establishment clause jurisprudence once again, frightening the little children and school attorneys.” (Lamb’s Chapel v. Moriches Union Free School District, 508 U.S. 384, 398-99 (1993)). Then head of Philadelphia’s Roman Catholic Archdiocese, Cardinal John Krol (1910-1996), who later went on to try to win tax credits for parents of children in religious schools, called opponents of the state law “emotional bigots,” “nativists and Ku Kluxers” – which would seem to underscore who might have benefitted had the Pennsylvania law been upheld.

But Lemon has been affirmed and cited time and time again since 1971. Even if the general population would wish it were backing a particular religion, as from time to time some polls have maintained, the First Amendment counsels to be careful what you wish for. As a check on mob rule, altering the “Lemon Test” could come back to bite the mob when its composition changes: if the state favored Christians today, who is to say the state may not favor Muslims tomorrow?

SIDEBAR: Who was Alton Lemon?

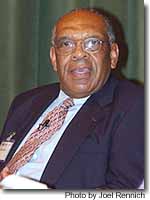

The lead plaintiff in Lemon v. Kurtzman was Alton T. Lemon (1928-2013), an Ethical Humanist and an African-American member of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). He was born 19 October 1928 in McDonough, GA, and reared a Baptist. He earned a degree in mathematics from Morehouse College in Atlanta in 1950, served in the U.S. Army, earned a master’s degree in social work from the University of Pennsylvania, worked in a series of government jobs and was active in the NAACP and the ACLU. He was also the first African-American president of the Ethical Humanist Society of Philadelphia.

The lead plaintiff in Lemon v. Kurtzman was Alton T. Lemon (1928-2013), an Ethical Humanist and an African-American member of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). He was born 19 October 1928 in McDonough, GA, and reared a Baptist. He earned a degree in mathematics from Morehouse College in Atlanta in 1950, served in the U.S. Army, earned a master’s degree in social work from the University of Pennsylvania, worked in a series of government jobs and was active in the NAACP and the ACLU. He was also the first African-American president of the Ethical Humanist Society of Philadelphia.

It is no accident that Lemon was asked to join the suit challenging the Pennsylvania law after he criticized it at an ACLU meeting. University of Virginia law professor Douglas Laycock said, “The case was decided against the backdrop of resistance to the desegregation of public schools, and the choice of Mr. Lemon, who was black, underscored the point.”

What of Alton Lemon’s personal beliefs? “I didn't start out in life to do anything like this,” Lemon told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 2003. But he noted that “separation of church and state is gradually losing ground, I regret to say.” He was suspicious that conservatives would establish a state church, if they could. “At this point in my life,” the then-76-year-old said, “I seriously wonder why we have religion. I am not so sure it does more good than harm. I think that the battle for church-state separation has to be a continuing fight.”

Alton Lemon died on 4 May 2013 in Jenkintown, PA, at age 84. It took the New York Times three weeks to find this important enough to publish his obituary (5/25/13).