Week in Freethought History (July 28-August 4)

Here’s your Week in Freethought History: This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

Last Sunday, July 29, but in 1644, the pope who will be remembered throughout history as the persecutor of Galileo, Urban VIII, died at Rome. Born on a date uncertain in April 1568 in Galileo’s ancestral home of Florence, (four years after Galileo’s birth), the future pope was reared among the wealthy and privileged. On the death of Gregory XV, he was elected pope in 1623 at age 55 and took the name Urban VIII. While the Thirty Years’ War raged between Catholics and Protestants in Europe, Urban canonized Ignatius of Loyola. Ignatius, of course, founded the Jesuits, an organization whose chief accomplishment was inciting the Thirty Years’ War.

Last Sunday, July 29, but in 1644, the pope who will be remembered throughout history as the persecutor of Galileo, Urban VIII, died at Rome. Born on a date uncertain in April 1568 in Galileo’s ancestral home of Florence, (four years after Galileo’s birth), the future pope was reared among the wealthy and privileged. On the death of Gregory XV, he was elected pope in 1623 at age 55 and took the name Urban VIII. While the Thirty Years’ War raged between Catholics and Protestants in Europe, Urban canonized Ignatius of Loyola. Ignatius, of course, founded the Jesuits, an organization whose chief accomplishment was inciting the Thirty Years’ War.

As for Urban and Galileo, the Catholic Encyclopedia can barely begrudge a mention of the savaging of the scientist, for which Urban is directly responsible. One Catholic apologist website has the temerity to write: “Urban … is connected with the famous condemnation of Galileo. The imprudent astronomer had been lured by his enemies on to the field of theology and as a result had been condemned by a commission of the Holy Office. He gave in, however, and suffered small inconvenience in a sort of house arrest. The affair was unfortunate...”

As for Urban and Galileo, the Catholic Encyclopedia can barely begrudge a mention of the savaging of the scientist, for which Urban is directly responsible. One Catholic apologist website has the temerity to write: “Urban … is connected with the famous condemnation of Galileo. The imprudent astronomer had been lured by his enemies on to the field of theology and as a result had been condemned by a commission of the Holy Office. He gave in, however, and suffered small inconvenience in a sort of house arrest. The affair was unfortunate...”

It takes great skill to assemble so many distortions into so few words. Urban was hated by the Romans for his nepotism. Far from being a friend, Urban directed Galileo’s every punishment, having taken great offense at his arguments against the Copernican, earth-centered system being annihilated in print by Galileo (Dialog, 1632). The contemporary documents show that “he was menaced with torture again and again by express order of Pope Urban.” Galileo’s “small inconvenience,” as the apologist puts it, was for the world-renowned scientist, already ailing and nearly blind, to be confined to his home, forced to recant and forbidden to teach and write what he knew to be true – and what he had demonstrated to be true! Urban ended his days by pouring the papal treasury into his corrupt family’s coffers, rather than financing the Catholic powers in the Thirty Years War. Even the Catholic Encyclopedia has to admit that “Urban’s greatest fault was his excessive nepotism.”

Last Monday, July 30, but in 1889, Emanuel Julius was born – later to become known as the book publisher E. Haldeman-Julius. Emanuel, already making his name at liberal newspapers, met and married Marcet Haldeman, a banker and heiress, who was the niece of Jane Addams of Hull House repute. Emanuel had a vision of making good literature available to large numbers at low prices, so he set up a printing plant in the small mid-western town of Girard, Kansas, and began producing what came to be known as his Little Blue Books. Marcet and E. Haldeman-Julius – they legally changed their names – became wealthy publishers throughout the nineteen-twenties and thirties. E. Haldeman-Julius expanded on his religious opinions in several of his own publications: “We advocate the atheistic philosophy because it is the only clear, consistent position which seems possible to us. As atheists … we declare that the God idea … is unreasonable and unprovable; we add, more vitally, that the God idea is an interference with the interests of human happiness and progress. We oppose religion not merely as a set of theological ideas; but we must also oppose religion as a political, social and moral influence detrimental to the welfare of humanity.”

Last Monday, July 30, but in 1889, Emanuel Julius was born – later to become known as the book publisher E. Haldeman-Julius. Emanuel, already making his name at liberal newspapers, met and married Marcet Haldeman, a banker and heiress, who was the niece of Jane Addams of Hull House repute. Emanuel had a vision of making good literature available to large numbers at low prices, so he set up a printing plant in the small mid-western town of Girard, Kansas, and began producing what came to be known as his Little Blue Books. Marcet and E. Haldeman-Julius – they legally changed their names – became wealthy publishers throughout the nineteen-twenties and thirties. E. Haldeman-Julius expanded on his religious opinions in several of his own publications: “We advocate the atheistic philosophy because it is the only clear, consistent position which seems possible to us. As atheists … we declare that the God idea … is unreasonable and unprovable; we add, more vitally, that the God idea is an interference with the interests of human happiness and progress. We oppose religion not merely as a set of theological ideas; but we must also oppose religion as a political, social and moral influence detrimental to the welfare of humanity.”

Last Tuesday, July 31, but in 1485, the source of the Arthurian legends as we know them today, eight romances known as Le Morte D’Arthur, was published in London. The work was written by Sir Thomas Malory (c 1405-1471), published by the father of printing, William Caxton (1422?-1491), and promotes what we today call the “Age of Chivalry.” This nobler time has been relentlessly romanticized in literature and film. It presumably lasted from 1100 to 1400 in England, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. Chivalry in myth – especially as outlined by historian Léon Gautier in 1891 – was a time of deep religious faith, respect for the weak, bravery in battle, veneration of women, generosity of spirit, truth and justice. This may come as a revelation to those who think morality is on the decline in the world today, but during the “Age of Chivalry” the noble and knightly classes of both sexes were saturated with sexual vice and violence, brigandry and theft, and uncommon corruption. Serious scholars describe the age, everyone went to church, as the worst period for morals in the history of civilization. You might conclude that if the “Age of Chivalry” was the apotheosis of Christianity, then gentle Jesus was a rascal.

Last Tuesday, July 31, but in 1485, the source of the Arthurian legends as we know them today, eight romances known as Le Morte D’Arthur, was published in London. The work was written by Sir Thomas Malory (c 1405-1471), published by the father of printing, William Caxton (1422?-1491), and promotes what we today call the “Age of Chivalry.” This nobler time has been relentlessly romanticized in literature and film. It presumably lasted from 1100 to 1400 in England, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. Chivalry in myth – especially as outlined by historian Léon Gautier in 1891 – was a time of deep religious faith, respect for the weak, bravery in battle, veneration of women, generosity of spirit, truth and justice. This may come as a revelation to those who think morality is on the decline in the world today, but during the “Age of Chivalry” the noble and knightly classes of both sexes were saturated with sexual vice and violence, brigandry and theft, and uncommon corruption. Serious scholars describe the age, everyone went to church, as the worst period for morals in the history of civilization. You might conclude that if the “Age of Chivalry” was the apotheosis of Christianity, then gentle Jesus was a rascal.

Last Wednesday, August 1, but in 1744, French botanist, zoologist, and natural philosopher Jean Baptiste Lamarck was born. Educated by Jesuits, the Marquis de Lamarck became a Deist and studied medicine, meteorology, and botany. When the Museum of Natural History was reorganized in 1793, Lamarck (then age forty-nine) taught himself zoology to win a professorship. While there, he published his famous work, Zoological Philosophy (1809), which proposed his Lamarckian theory of evolution: that organic changes are directly produced by the environment and transmitted; that is, the “inheritance of acquired characteristics.” Since discredited, his theory prepared the way, philosophically, for acceptance of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution 50 years later. Curiously, the Catholic Encyclopedia claims Lamarck, saying he was “neither an atheist, nor irreligious, nor an opponent of the Scriptures.” It is curious that the pinnacle of Roman Catholic scholarship cannot quote one word from Lamarck’s mouth attesting to his faith in Jesus or his expectation of immortality. As Lamarck put it, “Life is a purely physical phenomenon.” Lamarck himself noted that spiritual realities are unknowable, since “all knowledge that is not the genuine product of observation or of consequences deduced from observation is entirely groundless and illusory.” He may have been an Agnostic.

Last Wednesday, August 1, but in 1744, French botanist, zoologist, and natural philosopher Jean Baptiste Lamarck was born. Educated by Jesuits, the Marquis de Lamarck became a Deist and studied medicine, meteorology, and botany. When the Museum of Natural History was reorganized in 1793, Lamarck (then age forty-nine) taught himself zoology to win a professorship. While there, he published his famous work, Zoological Philosophy (1809), which proposed his Lamarckian theory of evolution: that organic changes are directly produced by the environment and transmitted; that is, the “inheritance of acquired characteristics.” Since discredited, his theory prepared the way, philosophically, for acceptance of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution 50 years later. Curiously, the Catholic Encyclopedia claims Lamarck, saying he was “neither an atheist, nor irreligious, nor an opponent of the Scriptures.” It is curious that the pinnacle of Roman Catholic scholarship cannot quote one word from Lamarck’s mouth attesting to his faith in Jesus or his expectation of immortality. As Lamarck put it, “Life is a purely physical phenomenon.” Lamarck himself noted that spiritual realities are unknowable, since “all knowledge that is not the genuine product of observation or of consequences deduced from observation is entirely groundless and illusory.” He may have been an Agnostic.

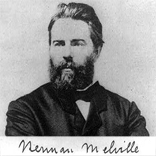

Also last Wednesday, August 1, but in 1819, the American novelist Herman Melville was born. It was his close friend Nathaniel Hawthorne who suggested that Melville change his book about his adventures on the high seas into the allegorical novel Moby Dick. It was a popular failure, but 30 years after the author’s death it began to be recognized as Melville’s masterpiece. Melville had seen predatory Christianity while sailing in the South Seas and acquired a thorough distaste for the religion. There, he witnessed not the faith, hope and charity he had been taught to expect, but “militaristic nationalism, ethnocentrism, slavery, hypocrisy and predatory capitalism.” The great white whale is, of course, Ahab’s image of a vengeful God. Ahab was no Atheist, and neither was Melville, who has the novel’s Presbyterian narrator, Ishmael, refer to his captain as a lunatic, thus evading a charge of blasphemy. To Ahab (as to Melville), God was a fiend. Called on his impiety by the Pequod’s pious first mate, Starbuck, Ahab replies, “Talk not to me of blasphemy, man. I’d strike the sun if it insulted me.”

Also last Wednesday, August 1, but in 1819, the American novelist Herman Melville was born. It was his close friend Nathaniel Hawthorne who suggested that Melville change his book about his adventures on the high seas into the allegorical novel Moby Dick. It was a popular failure, but 30 years after the author’s death it began to be recognized as Melville’s masterpiece. Melville had seen predatory Christianity while sailing in the South Seas and acquired a thorough distaste for the religion. There, he witnessed not the faith, hope and charity he had been taught to expect, but “militaristic nationalism, ethnocentrism, slavery, hypocrisy and predatory capitalism.” The great white whale is, of course, Ahab’s image of a vengeful God. Ahab was no Atheist, and neither was Melville, who has the novel’s Presbyterian narrator, Ishmael, refer to his captain as a lunatic, thus evading a charge of blasphemy. To Ahab (as to Melville), God was a fiend. Called on his impiety by the Pequod’s pious first mate, Starbuck, Ahab replies, “Talk not to me of blasphemy, man. I’d strike the sun if it insulted me.”

Last Thursday, August 2, but in 1820, British physicist John Tyndall was born. By the time he married, at age 56, Tyndall had become a well-known writer and lecturer on, and popularizer of, science, as well as an ardent defender of the theory of evolution. From his youth Tyndall had been interested in religion, and by the time he met and became friends with zoologist and Darwinist Thomas Henry Huxley, he was already a Rationalist. Among his friends were Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle, the poet Tennyson, English chemist and physicist Michael Faraday, and French chemist Louis Pasteur (whose germ theory of disease Tyndall defended). Like his friend Huxley, Tyndall was denounced as an Atheist and a Materialist. He was neither, though he discounted the Christian story and despised the social record of Roman Catholicism. “Let us beware, then,” said Tyndall, “of not considering religion noble; but let us beware still more of considering it true.”

Last Thursday, August 2, but in 1820, British physicist John Tyndall was born. By the time he married, at age 56, Tyndall had become a well-known writer and lecturer on, and popularizer of, science, as well as an ardent defender of the theory of evolution. From his youth Tyndall had been interested in religion, and by the time he met and became friends with zoologist and Darwinist Thomas Henry Huxley, he was already a Rationalist. Among his friends were Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle, the poet Tennyson, English chemist and physicist Michael Faraday, and French chemist Louis Pasteur (whose germ theory of disease Tyndall defended). Like his friend Huxley, Tyndall was denounced as an Atheist and a Materialist. He was neither, though he discounted the Christian story and despised the social record of Roman Catholicism. “Let us beware, then,” said Tyndall, “of not considering religion noble; but let us beware still more of considering it true.”

Yesterday, August 3, but in 1887, that the Edwardian British poet W.B. Yeats called “The most handsome man in England,” Rupert Brooke was born. His 1914 and Other Poems (1915) shows him to be a freethinker, especially in “Heaven,” which satirizes the Christian myth:

Yesterday, August 3, but in 1887, that the Edwardian British poet W.B. Yeats called “The most handsome man in England,” Rupert Brooke was born. His 1914 and Other Poems (1915) shows him to be a freethinker, especially in “Heaven,” which satirizes the Christian myth:

…Fish say, they have their Stream and Pond;

But is there anything Beyond?

This life cannot be All, they swear,

For how unpleasant, if it were!

…

And, sure, the reverent eye must see

A Purpose in Liquidity.

…But somewhere, beyond Space and Time,

Is wetter water, slimier slime!

And there (they trust) there swimmeth One

Who swam ere rivers were begun,

Immense, of fishy form and mind,

Squamous, omnipotent, and kind;

…And in that Heaven of all their wish,

There shall be no more land, say fish.

Today, August 4, but in 1792, the third-greatest British poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley, was born. Along with developing a strong dislike for political tyranny, after reading the radical writings of Thomas Paine, William Godwin and Baron D’Holbach, he became an Atheist and a Materialist – a position he maintained until his early death, shortly before his thirtieth birthday. He was educated at Eton, where he was known as “Shelley the Atheist,” and at Oxford. In an 1811 pamphlet called The Necessity of Atheism, he attacked compulsory Christian practice, writing this gem (after D’Holbach): “If God has spoken, why is the world not convinced?” So shocked was Oxford that Shelley was expelled. Shelley fell in love with the beautiful and accomplished daughter of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, lived with her until his first wife died, then married her – the future author of Frankenstein. With Mary in Italy, Shelley wrote some of his greatest works. Percy Bysshe Shelley once said, “It is easier to suppose that the universe has existed for all eternity than to conceive a being beyond its limits capable of creating it.”

Today, August 4, but in 1792, the third-greatest British poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley, was born. Along with developing a strong dislike for political tyranny, after reading the radical writings of Thomas Paine, William Godwin and Baron D’Holbach, he became an Atheist and a Materialist – a position he maintained until his early death, shortly before his thirtieth birthday. He was educated at Eton, where he was known as “Shelley the Atheist,” and at Oxford. In an 1811 pamphlet called The Necessity of Atheism, he attacked compulsory Christian practice, writing this gem (after D’Holbach): “If God has spoken, why is the world not convinced?” So shocked was Oxford that Shelley was expelled. Shelley fell in love with the beautiful and accomplished daughter of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, lived with her until his first wife died, then married her – the future author of Frankenstein. With Mary in Italy, Shelley wrote some of his greatest works. Percy Bysshe Shelley once said, “It is easier to suppose that the universe has existed for all eternity than to conceive a being beyond its limits capable of creating it.”

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links above.