Week in Freethought History (June 3-9)

Here’s your Week in Freethought History: This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

Last Sunday, June 3, but in 1727, the Scot called “the first great British geologist,” James Hutton was born. Hutton studied medicine, took his degree, but, there being no employment for him, he almost gave up science for agriculture. In 1785, Hutton submitted a paper to the newly established Royal Society of Edinburgh outlining his Theory of the Earth, an idea that pretty much invented the science of geology. But this theory flew in the face of the Biblical teaching that the earth had been transformed only once, catastrophically, by a universal Flood. Since the beginning of the Christian Era, the book of Genesis was the only acceptable book of geology. Before fundamentalist Islam clamped shut Muslim minds, Avicenna in the 11th century came up with a gradualist theory of the formation of the earth. But in Christian Europe the clerics thought research into the age of rocks distracted the mind from the Rock of Ages – and led to infidelity and Atheism. Only with James Hutton, and later with Darwin, was the truth of the scientific theory of gradualism gradually accepted.

Last Sunday, June 3, but in 1727, the Scot called “the first great British geologist,” James Hutton was born. Hutton studied medicine, took his degree, but, there being no employment for him, he almost gave up science for agriculture. In 1785, Hutton submitted a paper to the newly established Royal Society of Edinburgh outlining his Theory of the Earth, an idea that pretty much invented the science of geology. But this theory flew in the face of the Biblical teaching that the earth had been transformed only once, catastrophically, by a universal Flood. Since the beginning of the Christian Era, the book of Genesis was the only acceptable book of geology. Before fundamentalist Islam clamped shut Muslim minds, Avicenna in the 11th century came up with a gradualist theory of the formation of the earth. But in Christian Europe the clerics thought research into the age of rocks distracted the mind from the Rock of Ages – and led to infidelity and Atheism. Only with James Hutton, and later with Darwin, was the truth of the scientific theory of gradualism gradually accepted.

Last Monday, June 4, but in 1648, Margery Jones became the first woman in Massachusetts to be executed explicitly for being a witch – that is, for dispensing healing herbs. Bay Colony Governor John Winthrop wrote in his diary: “Her behavior at the trial was very intemperate, lying notoriously, and railing upon the jury and witnesses, etc. and in like distemper she died. The same day and hour she was executed there was a very great tempest at Connecticut, which blew down many trees, etc.”

Last Monday, June 4, but in 1648, Margery Jones became the first woman in Massachusetts to be executed explicitly for being a witch – that is, for dispensing healing herbs. Bay Colony Governor John Winthrop wrote in his diary: “Her behavior at the trial was very intemperate, lying notoriously, and railing upon the jury and witnesses, etc. and in like distemper she died. The same day and hour she was executed there was a very great tempest at Connecticut, which blew down many trees, etc.”

That was nothing like the tempest over woman suffrage that took 70 years to subside: On June 4 in 1919, the words, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex” were written into the US Constitution. The so-called “Susan Anthony Amendment” passed the Senate 56 to 25, or two votes more than the two-thirds majority necessary. Tennessee took the honor of becoming the final state to ratify the 19th Amendment – by a one-vote majority – on 19 August 1920. What was the role of religion in winning this basic civil right? The 19th Amendment was named for Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906), who co-authored a History of Woman Suffrage (1881-1887), with Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) and Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826-1898), and who co-founded the National Woman Suffrage Association. Anthony was an Agnostic. Stanton, who answered in the negative in her essay “What Has Christianity Done for Women?”, and Gage, author of Woman, Church and the State (1893), were also Agnostics. So were Fanny Wright (1795-1852), Susan B. Anthony’s biographer Ida Husted Harper (1851-1931), Ernestine Rose (1810-1882), Lucy Colman (1817-1906), Lydia Child (1802-1880), Helen Hamilton Gardener (1853-1925), Eva Ingersoll-Brown, and 90 percent of the rest of the early leaders – and also, perhaps, 50 percent of today’s leaders. But now that women can vote, it will be more difficult to burn them as witches…

That was nothing like the tempest over woman suffrage that took 70 years to subside: On June 4 in 1919, the words, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex” were written into the US Constitution. The so-called “Susan Anthony Amendment” passed the Senate 56 to 25, or two votes more than the two-thirds majority necessary. Tennessee took the honor of becoming the final state to ratify the 19th Amendment – by a one-vote majority – on 19 August 1920. What was the role of religion in winning this basic civil right? The 19th Amendment was named for Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906), who co-authored a History of Woman Suffrage (1881-1887), with Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) and Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826-1898), and who co-founded the National Woman Suffrage Association. Anthony was an Agnostic. Stanton, who answered in the negative in her essay “What Has Christianity Done for Women?”, and Gage, author of Woman, Church and the State (1893), were also Agnostics. So were Fanny Wright (1795-1852), Susan B. Anthony’s biographer Ida Husted Harper (1851-1931), Ernestine Rose (1810-1882), Lucy Colman (1817-1906), Lydia Child (1802-1880), Helen Hamilton Gardener (1853-1925), Eva Ingersoll-Brown, and 90 percent of the rest of the early leaders – and also, perhaps, 50 percent of today’s leaders. But now that women can vote, it will be more difficult to burn them as witches…

Last Tuesday, June 5, but in 1723, Scottish economist Adam Smith was born. Early in his education, while attending Glasgow and Oxford Universities, he adopted the philosophy of fellow Scot David Hume (1711-1776), who later became a good friend. He declined an obligation to enter the Scottish ministry, but instead at age 28 became a professor of logic, and later of moral philosophy while still living at home with his mother. He would remain there all his life, never marrying. Clerical Scotland was startled to read Smith’s 1759 Theory of Moral Sentiments, a work that espoused a naturalist, that is to say, a Deistic world view. The clerical reaction persuaded Smith that further advocacy of the idea that morality comes not from God but from sympathy, would not help his career. Smith visited Voltaire at Geneva, who persuaded Smith to believe that, “Science is the great antidote to the poison of enthusiasm and superstition.” And he began to work out his own ideas on political economy. In the same year that his friend David Hume died, 1776, Smith published the work that entitles him to be called “the father of British political economy”: Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, popularly known as Wealth of Nations. When Hume died, Smith edited some of his friend’s non-controversial papers for publication and even wrote a sympathetic life of Hume, which Chalmers’ General Biographical Dictionary describes as “a powerful blow against Christianity.” The work caused such a stir among the clergy in Scotland, especially from the Bishop of Norwich, John Home (1722-1808), who practically accused Smith of Atheism. But Smith was trying to make a living as a public employee, so he remained silent about his religious beliefs. It is generally accepted that Adam Smith was at most a Deist, but considering how close he was to Hume, he may in fact have been an Agnostic.

Last Tuesday, June 5, but in 1723, Scottish economist Adam Smith was born. Early in his education, while attending Glasgow and Oxford Universities, he adopted the philosophy of fellow Scot David Hume (1711-1776), who later became a good friend. He declined an obligation to enter the Scottish ministry, but instead at age 28 became a professor of logic, and later of moral philosophy while still living at home with his mother. He would remain there all his life, never marrying. Clerical Scotland was startled to read Smith’s 1759 Theory of Moral Sentiments, a work that espoused a naturalist, that is to say, a Deistic world view. The clerical reaction persuaded Smith that further advocacy of the idea that morality comes not from God but from sympathy, would not help his career. Smith visited Voltaire at Geneva, who persuaded Smith to believe that, “Science is the great antidote to the poison of enthusiasm and superstition.” And he began to work out his own ideas on political economy. In the same year that his friend David Hume died, 1776, Smith published the work that entitles him to be called “the father of British political economy”: Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, popularly known as Wealth of Nations. When Hume died, Smith edited some of his friend’s non-controversial papers for publication and even wrote a sympathetic life of Hume, which Chalmers’ General Biographical Dictionary describes as “a powerful blow against Christianity.” The work caused such a stir among the clergy in Scotland, especially from the Bishop of Norwich, John Home (1722-1808), who practically accused Smith of Atheism. But Smith was trying to make a living as a public employee, so he remained silent about his religious beliefs. It is generally accepted that Adam Smith was at most a Deist, but considering how close he was to Hume, he may in fact have been an Agnostic.

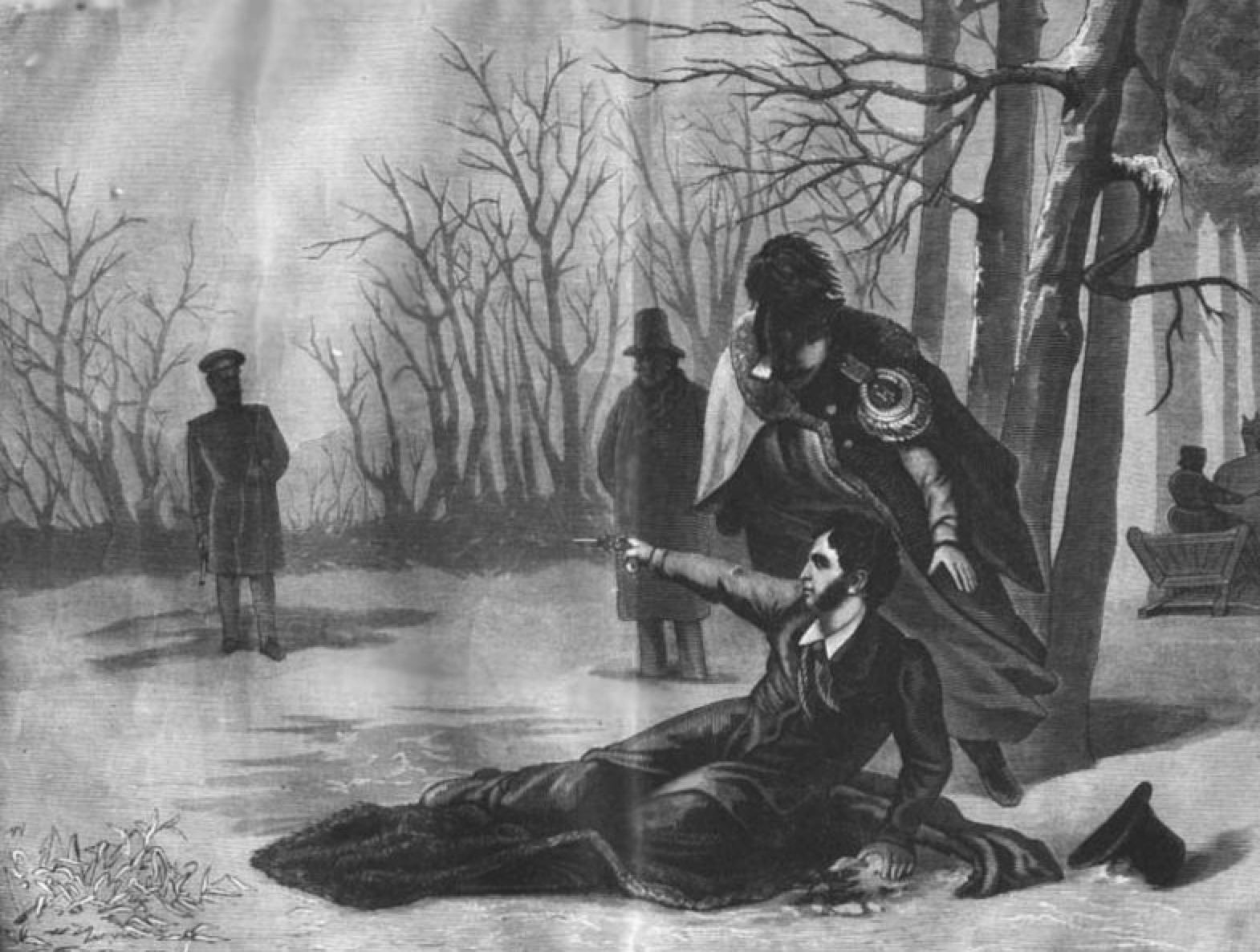

Last Wednesday, June 6, but in 1799, the founder of modern Russian literature, Alexander S. Pushkin (Алекса́ндр С. Пу́шкин) was born. His family was aristocratic but poor. Nevertheless, Pushkin managed to acquire an education and between 1811-1817 he began writing his first major work, Ruslan and Ludmila (Руслан и Людмила), a fairy story in verse based on Russian folk tales his grandmother had told him – in French. Pushkin’s masterpiece, Eugene Onegin (Евге́ний Оне́гин), a novel in verse published between 1823 and 1831, features a duel between his characters, Lensky and Onegin, over a woman named Olga. Life imitates art: In Moscow Pushkin met, and in 1831 married, the beautiful 16-year-old, Natalia Goncharova. Pushkin was twice her age. But rumors of Natalia’s infidelities afflicted Pushkin. She was seen with the French Baron George-Charles Dantes once too often at social functions, so Pushkin felt compelled to challenge Dantes to a duel on November 16, 1836.

Last Wednesday, June 6, but in 1799, the founder of modern Russian literature, Alexander S. Pushkin (Алекса́ндр С. Пу́шкин) was born. His family was aristocratic but poor. Nevertheless, Pushkin managed to acquire an education and between 1811-1817 he began writing his first major work, Ruslan and Ludmila (Руслан и Людмила), a fairy story in verse based on Russian folk tales his grandmother had told him – in French. Pushkin’s masterpiece, Eugene Onegin (Евге́ний Оне́гин), a novel in verse published between 1823 and 1831, features a duel between his characters, Lensky and Onegin, over a woman named Olga. Life imitates art: In Moscow Pushkin met, and in 1831 married, the beautiful 16-year-old, Natalia Goncharova. Pushkin was twice her age. But rumors of Natalia’s infidelities afflicted Pushkin. She was seen with the French Baron George-Charles Dantes once too often at social functions, so Pushkin felt compelled to challenge Dantes to a duel on November 16, 1836.

Dueling was one of the more noxious innovations introduced after Europe was compelled to adopt Christianity. So much for the claim that Christianity tamed the passions of the barbarians! The practice was not confined to men: in the Middle Ages, women fought their own duels – sometimes against men. In 1165, Pope Alexander II, instead of condemning duels, simply forbade wounded priests from saying Mass. If anything, the practice expanded during the so-called Age of Chivalry. As late as 1830 London newspapers carried advertisements for how-to books on dueling. Spain, France, Britain, Ireland, Russia, Germany and the rest of the Christianized world had their own longstanding traditions of settling insults to honor through personal combat – and no gentle Galilean stood in their way. In the US, perhaps the most famous duel was on July 11, 1804, when Aaron Burr shot Alexander Hamilton. Dueling was not just about blood for honor. Pushkin’s duel extinguished a brilliant poet’s life: shot on a snow-covered field outside of St. Petersburg, he died from his wounds two days later. It was 10 February 1837, and Pushkin was 37. What great works might he yet have created? A monument stands in the very center of Moscow where, on this date each year, people gather to honor the memory of Alexander Pushkin, cut down by a bullet that no creed tried to stop.

Dueling was one of the more noxious innovations introduced after Europe was compelled to adopt Christianity. So much for the claim that Christianity tamed the passions of the barbarians! The practice was not confined to men: in the Middle Ages, women fought their own duels – sometimes against men. In 1165, Pope Alexander II, instead of condemning duels, simply forbade wounded priests from saying Mass. If anything, the practice expanded during the so-called Age of Chivalry. As late as 1830 London newspapers carried advertisements for how-to books on dueling. Spain, France, Britain, Ireland, Russia, Germany and the rest of the Christianized world had their own longstanding traditions of settling insults to honor through personal combat – and no gentle Galilean stood in their way. In the US, perhaps the most famous duel was on July 11, 1804, when Aaron Burr shot Alexander Hamilton. Dueling was not just about blood for honor. Pushkin’s duel extinguished a brilliant poet’s life: shot on a snow-covered field outside of St. Petersburg, he died from his wounds two days later. It was 10 February 1837, and Pushkin was 37. What great works might he yet have created? A monument stands in the very center of Moscow where, on this date each year, people gather to honor the memory of Alexander Pushkin, cut down by a bullet that no creed tried to stop.

Last Thursday, June 7, but in 632, Muhammad, the founder of Islam, died of a stroke at Medina. Muhammad (محمد) was born on a date uncertain in 570 in Mecca, in what is now Saudi Arabia, orphaned, brought up by an uncle, and became a camel driver and shepherd as a boy. Muhammad thought it tragic that his Arab race were idolaters and polytheistic, so in 610 (he was about 40) he started having visions from the Angel Gabriel and began a life as a prophet and teacher. Islam (الإسلام), means “submission,” as in submission to the one God. In 622 Muhammad was forced to flee from Mecca to Yathrib, which is now called Medina, and found his religion welcomed there. The date of that flight is called the hegira (هجرة) and that event marks the beginning of the Muhammadan era. The holy book of Islam, the Qur’an (القرآن), means “the recitation” or “the lesson” – of Allah. Because Muhammad was illiterate, he memorized his visions and dictated them afterwards, sometimes long enough afterwards to have forgotten contradictory earlier visions.

Last Thursday, June 7, but in 632, Muhammad, the founder of Islam, died of a stroke at Medina. Muhammad (محمد) was born on a date uncertain in 570 in Mecca, in what is now Saudi Arabia, orphaned, brought up by an uncle, and became a camel driver and shepherd as a boy. Muhammad thought it tragic that his Arab race were idolaters and polytheistic, so in 610 (he was about 40) he started having visions from the Angel Gabriel and began a life as a prophet and teacher. Islam (الإسلام), means “submission,” as in submission to the one God. In 622 Muhammad was forced to flee from Mecca to Yathrib, which is now called Medina, and found his religion welcomed there. The date of that flight is called the hegira (هجرة) and that event marks the beginning of the Muhammadan era. The holy book of Islam, the Qur’an (القرآن), means “the recitation” or “the lesson” – of Allah. Because Muhammad was illiterate, he memorized his visions and dictated them afterwards, sometimes long enough afterwards to have forgotten contradictory earlier visions.

Inasmuch as the Qur’an reflects the ideas of Muhammad, a few points need to be made. First, neither in Islamic history nor in the Qur’an is Islam anymore a “religion of peace” than Christianity – like Christianity, it all depends on what you accept and what you reject in your interpretation of your holy book. Second, and for the same reason as Christianity, it is not true that Islam is a tolerant religion. If we discount the early suras in the Koran, which were revealed when Muhammad was struggling for acceptance, and concentrate on the later ones, written when Muhammad was master of Arabia, you will understand the context of holy words such as “[22.9] As for the unbelievers, for them garments of fire shall be cut and there shall be poured over their heads boiling water whereby whatever is in their bowels and skins shall be dissolved and they will be punished with hooked iron rods.” And [47.4] “When you meet the unbelievers, strike off their heads; then when you have made wide slaughter among them, carefully tie up the remaining captives.”

Inasmuch as the Qur’an reflects the ideas of Muhammad, a few points need to be made. First, neither in Islamic history nor in the Qur’an is Islam anymore a “religion of peace” than Christianity – like Christianity, it all depends on what you accept and what you reject in your interpretation of your holy book. Second, and for the same reason as Christianity, it is not true that Islam is a tolerant religion. If we discount the early suras in the Koran, which were revealed when Muhammad was struggling for acceptance, and concentrate on the later ones, written when Muhammad was master of Arabia, you will understand the context of holy words such as “[22.9] As for the unbelievers, for them garments of fire shall be cut and there shall be poured over their heads boiling water whereby whatever is in their bowels and skins shall be dissolved and they will be punished with hooked iron rods.” And [47.4] “When you meet the unbelievers, strike off their heads; then when you have made wide slaughter among them, carefully tie up the remaining captives.”

It was yesterday June 8, but in 1810, that German Romantic composer Robert Schumann was born. His mother encouraged him to study law, but Robert was distracted by his love of music and poetry. Deciding at last to undertake a career as a concert pianist, he lived with and studied under the master, Friedrich Weick. But Schumann managed to injure his right hand and soon it became impossible to play. Schumann fell back onto composition. However, his studies had one other benefit: he fell in love with his master’s daughter, Clara Weick, a polished pianist and composer in her own right. But it was five years before they were able to marry, over her father’s strong opposition (1840). Although religious compositions made up a significant part of Schumann’s works, he was a Pantheist like his countryman, Goethe.

It was yesterday June 8, but in 1810, that German Romantic composer Robert Schumann was born. His mother encouraged him to study law, but Robert was distracted by his love of music and poetry. Deciding at last to undertake a career as a concert pianist, he lived with and studied under the master, Friedrich Weick. But Schumann managed to injure his right hand and soon it became impossible to play. Schumann fell back onto composition. However, his studies had one other benefit: he fell in love with his master’s daughter, Clara Weick, a polished pianist and composer in her own right. But it was five years before they were able to marry, over her father’s strong opposition (1840). Although religious compositions made up a significant part of Schumann’s works, he was a Pantheist like his countryman, Goethe.

Today, June 9, but in 1843, the first woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, Baroness Bertha von Suttner, was born in Prague, in what is now the Czech Republic. She was the posthumous daughter of Field Marshal Count Kinsky, yet despite the militaristic tradition in which she was reared, Bertha became a peace activist and an international figure in the movement to offer arbitration in place of warfare between nations. Bertha tried to popularize the idea of the Permanent Court of Arbitration. She was the only woman at the First Hague Convention of 1899. Her former employer, Alfred Nobel, had established a peace prize to be awarded after his death, and in 1905 Bertha won this much-deserved award – the first woman to be so honored. It is arguable that no such award would have existed had not Von Suttner and Alfred Nobel been so close. And Baroness von Suttner made no secret of her Rationalism. Her beliefs might best be described as Pantheism, seeing God only in nature. She died on 21 June 1914, age 71, two months before the eruption of the world war she had warned and struggled against.

Today, June 9, but in 1843, the first woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, Baroness Bertha von Suttner, was born in Prague, in what is now the Czech Republic. She was the posthumous daughter of Field Marshal Count Kinsky, yet despite the militaristic tradition in which she was reared, Bertha became a peace activist and an international figure in the movement to offer arbitration in place of warfare between nations. Bertha tried to popularize the idea of the Permanent Court of Arbitration. She was the only woman at the First Hague Convention of 1899. Her former employer, Alfred Nobel, had established a peace prize to be awarded after his death, and in 1905 Bertha won this much-deserved award – the first woman to be so honored. It is arguable that no such award would have existed had not Von Suttner and Alfred Nobel been so close. And Baroness von Suttner made no secret of her Rationalism. Her beliefs might best be described as Pantheism, seeing God only in nature. She died on 21 June 1914, age 71, two months before the eruption of the world war she had warned and struggled against.

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in the excerpts above.