Week in Freethought History (May 20-26)

Here’s your Week in Freethought History: This is more than just a calendar of events or mini-biographies – it’s a reminder that, no matter how isolated and alone we may feel at times, we as freethinkers are neither unique nor alone in the world.

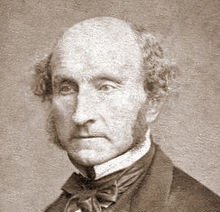

Last Sunday, May 20, but 206 years ago, my namesake, John Stuart Mill, “the Saint of Rationalism,” was born (1806). Mill’s philosophy was influenced by the freethinker Jeremy Bentham and, to this day, John Stuart Mill’s name is almost synonymous with the philosophy of Utilitarianism. In his 1859 essay, On Liberty, Mill masterfully details why free speech is a logical necessity and most profoundly influenced yours truly: “First, if any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility. Secondly, though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of truth; and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied. Thirdly, even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth; unless it is suffered to be, and actually is, vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little comprehension or feeling of its rational grounds. And not only this, but, fourthly, the meaning of the doctrine itself will be in danger of being lost, or enfeebled, and deprived of its vital effect on the character and conduct: the dogma becoming a mere formal profession, inefficacious for good, but cumbering the ground, and preventing the growth of any real and heartfelt conviction, from reason or personal experience.”

Last Sunday, May 20, but 206 years ago, my namesake, John Stuart Mill, “the Saint of Rationalism,” was born (1806). Mill’s philosophy was influenced by the freethinker Jeremy Bentham and, to this day, John Stuart Mill’s name is almost synonymous with the philosophy of Utilitarianism. In his 1859 essay, On Liberty, Mill masterfully details why free speech is a logical necessity and most profoundly influenced yours truly: “First, if any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility. Secondly, though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of truth; and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied. Thirdly, even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth; unless it is suffered to be, and actually is, vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little comprehension or feeling of its rational grounds. And not only this, but, fourthly, the meaning of the doctrine itself will be in danger of being lost, or enfeebled, and deprived of its vital effect on the character and conduct: the dogma becoming a mere formal profession, inefficacious for good, but cumbering the ground, and preventing the growth of any real and heartfelt conviction, from reason or personal experience.”

Also on May 20, but 213 years ago, the prolific French writer, Honoré de Balzac was born (1799). Sometimes ironically called “the Christ of Modern Art,” his radical Rationalism pervades all Balzac’s work. Indeed, the work for which he is chiefly known, a prodigious collection of novels and short stories giving a view of French life in city and country called The Human Comedy, which he conceived in 1830, was patterned on Dante’s Divine Comedy, but with an obviously secular worldview. In an 1836 short story, “The Atheist’s Mass,” Balzac describes his main character, Dr. Desplein, as having an “atheism … like that of many scientific men… such as religious people declare to be impossible. This opinion could scarcely exist otherwise in a man who was accustomed from his youth to dissect the creature above all others … to hunt through all his organs without ever finding the individual soul, which is indispensable to religious theory. …

Also on May 20, but 213 years ago, the prolific French writer, Honoré de Balzac was born (1799). Sometimes ironically called “the Christ of Modern Art,” his radical Rationalism pervades all Balzac’s work. Indeed, the work for which he is chiefly known, a prodigious collection of novels and short stories giving a view of French life in city and country called The Human Comedy, which he conceived in 1830, was patterned on Dante’s Divine Comedy, but with an obviously secular worldview. In an 1836 short story, “The Atheist’s Mass,” Balzac describes his main character, Dr. Desplein, as having an “atheism … like that of many scientific men… such as religious people declare to be impossible. This opinion could scarcely exist otherwise in a man who was accustomed from his youth to dissect the creature above all others … to hunt through all his organs without ever finding the individual soul, which is indispensable to religious theory. …

Monday, May 21, but 324 years ago, the English essayist, critic, satirist and poet Alexander Pope was born (1688). The son of a Catholic convert, and in spite of the anti-Catholic prejudice of the time, Pope became one of the brightest lights of the Enlightenment. By the time he published his Essay on Man (1733), Pope had abandoned Catholicism, and begun associating with skeptics. In his Essay on Man we find proof of Pope’s Deism: “Know thou thyself, presume not God to scan; / The proper study of mankind is man.” Pope was temperate in an age of heavy drinking and drug use, as well as kind and generous to friends – among whom he counted Jonathan Swift, the author of Gulliver’s Travels. Although the Catholic Encyclopedia claims him for one of the faithful, in an earlier age, a Deist of Pope’s beliefs would have been tried and either burned or hanged for impiety. Today, no longer having the power to do that, the Catholic Church lovingly takes him in his arms, so long at it can call him a Catholic poet. It was Alexander Pope who wrote, “To err is human, to forgive divine.”

Monday, May 21, but 324 years ago, the English essayist, critic, satirist and poet Alexander Pope was born (1688). The son of a Catholic convert, and in spite of the anti-Catholic prejudice of the time, Pope became one of the brightest lights of the Enlightenment. By the time he published his Essay on Man (1733), Pope had abandoned Catholicism, and begun associating with skeptics. In his Essay on Man we find proof of Pope’s Deism: “Know thou thyself, presume not God to scan; / The proper study of mankind is man.” Pope was temperate in an age of heavy drinking and drug use, as well as kind and generous to friends – among whom he counted Jonathan Swift, the author of Gulliver’s Travels. Although the Catholic Encyclopedia claims him for one of the faithful, in an earlier age, a Deist of Pope’s beliefs would have been tried and either burned or hanged for impiety. Today, no longer having the power to do that, the Catholic Church lovingly takes him in his arms, so long at it can call him a Catholic poet. It was Alexander Pope who wrote, “To err is human, to forgive divine.”

Tuesday, May 22, but 199 years ago, German Romantic composer Richard Wagner was born (1813). Wagner was largely self-taught in music. He is justly criticized for his anti-Semitism, but that Adolph Hitler agreed with Wagner in this respect is not Wagner’s fault. Yet opera (Music Drama) was never the same after Wagner. His librettos, most of which he wrote himself, were chiefly based on Germanic traditions and legends, so his investment in Christian theology was slight: one critic said that Wagner was “a Christian in a large sense, but not a man of the Church,” and that he had “little taste for the otherworldly speculations of dogmatic theology.” Wagner subscribed to the Atheistic views of German philosopher Karl Feuerbach, but had a sentimental regard for Christian mythology. Therefore, Nietzsche’s attack on Wagner for reverting to Christianity was unfair: Wagner wrote his most powerful music in his Ring years, when he was an Atheist.

Tuesday, May 22, but 199 years ago, German Romantic composer Richard Wagner was born (1813). Wagner was largely self-taught in music. He is justly criticized for his anti-Semitism, but that Adolph Hitler agreed with Wagner in this respect is not Wagner’s fault. Yet opera (Music Drama) was never the same after Wagner. His librettos, most of which he wrote himself, were chiefly based on Germanic traditions and legends, so his investment in Christian theology was slight: one critic said that Wagner was “a Christian in a large sense, but not a man of the Church,” and that he had “little taste for the otherworldly speculations of dogmatic theology.” Wagner subscribed to the Atheistic views of German philosopher Karl Feuerbach, but had a sentimental regard for Christian mythology. Therefore, Nietzsche’s attack on Wagner for reverting to Christianity was unfair: Wagner wrote his most powerful music in his Ring years, when he was an Atheist.

Wednesday, May 23, under the sign of Gemini, which places the date between 18 May and 17 June, but 747 years ago, the author of the Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri, was born (1265). Dante is chiefly remembered for his three-part poem, the Divine Comedy, written in vernacular Italian when most writers used Latin. What is telling about the Divine Comedy is that it was the first book written in Christian Europe since Augustine’s City of God (completed in 426) which any but a professor of literature now reads – including the pagan epic Beowulf (c. 725). Think about it! In nearly 900 years of the Ages of Faith, there was nothing written, inspired by Christian civilization, that is now considered of literary merit. There is no comparable dry period of world literature, before or since. The Catholic Encyclopedia claims Dante for the Church, but it is dishonest to claim, as the Catholic Encyclopedia does, that Dante’s “theological position as an orthodox Catholic has been amply and repeatedly vindicated,” when there are numerous and important doctrinal differences in his greatest work. But Dante’s standing as a precursor of the Reformation, and as a giant of early Italian poetry, is beyond debate.

Wednesday, May 23, under the sign of Gemini, which places the date between 18 May and 17 June, but 747 years ago, the author of the Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri, was born (1265). Dante is chiefly remembered for his three-part poem, the Divine Comedy, written in vernacular Italian when most writers used Latin. What is telling about the Divine Comedy is that it was the first book written in Christian Europe since Augustine’s City of God (completed in 426) which any but a professor of literature now reads – including the pagan epic Beowulf (c. 725). Think about it! In nearly 900 years of the Ages of Faith, there was nothing written, inspired by Christian civilization, that is now considered of literary merit. There is no comparable dry period of world literature, before or since. The Catholic Encyclopedia claims Dante for the Church, but it is dishonest to claim, as the Catholic Encyclopedia does, that Dante’s “theological position as an orthodox Catholic has been amply and repeatedly vindicated,” when there are numerous and important doctrinal differences in his greatest work. But Dante’s standing as a precursor of the Reformation, and as a giant of early Italian poetry, is beyond debate.

Thursday, May 24, but 168 years ago, Samuel Morse received the message “What hath God wrought,” which inaugurated long-distance coded communication over the first telegraph line strung from Baltimore, Maryland, to an astonished Congress at the Old Supreme Court Chamber in the United States Capitol (1844). The four words are the coda to a bible verse in Numbers 23:23. “What hath God wrought” seems a peculiar reference, but considered in context, the choice of the biblical line is better understood: Samuel Morse (1791-1872) was an organizer and polemicist of the anti-immigrant and anti-Roman Catholic “Nativist” movement of the mid-19th century. Moreover, more than a decade before the American Civil War, Morse came down on the wrong side of history in defending the institution of slavery in the United States as divinely sanctioned. So “What hath God wrought” comes from the same source that propagates bigotry and oppression. Giving credit to God for a work of man may in some circles be a sign of humility, but it is better described as a characteristic of intellectual slavery. It deflects credit to praise God for what man has wrought, without any measure of help from skygods.

Thursday, May 24, but 168 years ago, Samuel Morse received the message “What hath God wrought,” which inaugurated long-distance coded communication over the first telegraph line strung from Baltimore, Maryland, to an astonished Congress at the Old Supreme Court Chamber in the United States Capitol (1844). The four words are the coda to a bible verse in Numbers 23:23. “What hath God wrought” seems a peculiar reference, but considered in context, the choice of the biblical line is better understood: Samuel Morse (1791-1872) was an organizer and polemicist of the anti-immigrant and anti-Roman Catholic “Nativist” movement of the mid-19th century. Moreover, more than a decade before the American Civil War, Morse came down on the wrong side of history in defending the institution of slavery in the United States as divinely sanctioned. So “What hath God wrought” comes from the same source that propagates bigotry and oppression. Giving credit to God for a work of man may in some circles be a sign of humility, but it is better described as a characteristic of intellectual slavery. It deflects credit to praise God for what man has wrought, without any measure of help from skygods.

Friday, May 25, brings us three famous freethinkers—

English actor Sir Ian McKellen was born on this date 73 years ago (1939). In addition to his many theatrical roles, McKellen showed up in memorable film roles, such as the Middle Earth wizard Gandalf in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, based on the books by J.R.R. Tokein. The films somehow dodged much of the fundamentalist Christian outrage consequent to the Harry Potter films. “[M]aybe Tolkien’s work is relatively immune from Christian attacks because of his own Catholic faith,” mused McKellen in 2002, “On the other hand, an atheist friend of mine said how refreshing it was to see a film about good and evil which doesn’t link morality to religion.” In a 1996 profile, McKellen said, “I’m an atheist. So God, if She exists, isn’t really a part of my life.”

English actor Sir Ian McKellen was born on this date 73 years ago (1939). In addition to his many theatrical roles, McKellen showed up in memorable film roles, such as the Middle Earth wizard Gandalf in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, based on the books by J.R.R. Tokein. The films somehow dodged much of the fundamentalist Christian outrage consequent to the Harry Potter films. “[M]aybe Tolkien’s work is relatively immune from Christian attacks because of his own Catholic faith,” mused McKellen in 2002, “On the other hand, an atheist friend of mine said how refreshing it was to see a film about good and evil which doesn’t link morality to religion.” In a 1996 profile, McKellen said, “I’m an atheist. So God, if She exists, isn’t really a part of my life.”

On May 25, 77 years ago, Canadian novelist W.P. Kinsella was born (1935). A writer of baseball fiction, Kinsella’s bestselling 1982 novel, Shoeless Joe, was made into the very successful 1989 motion picture Field of Dreams. Kinsella won the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame’s Jack Graney Award for Shoeless Joe. Many of Kinsella’s novels and stories have supernatural elements. Even so, he is reported to be a member of American Atheists by the British Columbia Humanist Association. In the 1996 book Brave Souls: Writers and Artists Wrestle with God, Love, Death and the Things that Matter, by fellow Canadian Douglas Todd, W.P. Kinsella is profiled as an atheist.

On May 25, 77 years ago, Canadian novelist W.P. Kinsella was born (1935). A writer of baseball fiction, Kinsella’s bestselling 1982 novel, Shoeless Joe, was made into the very successful 1989 motion picture Field of Dreams. Kinsella won the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame’s Jack Graney Award for Shoeless Joe. Many of Kinsella’s novels and stories have supernatural elements. Even so, he is reported to be a member of American Atheists by the British Columbia Humanist Association. In the 1996 book Brave Souls: Writers and Artists Wrestle with God, Love, Death and the Things that Matter, by fellow Canadian Douglas Todd, W.P. Kinsella is profiled as an atheist.

On May 25, 209 years ago, American poet, essayist and moralist philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson was born (1803). After graduating Harvard in 1821, and teaching for a few years, Emerson was ordained into the Unitarian ministry. Six years later he resigned over doctrinal differences to form the group coming to be known as Transcendentalists, a company of writers and thinkers expressing an ethical idealism. The author of such well-known essays as “Self-Reliance,” “Circles,” “The Poet” and “Experience,” Emerson repudiated even the amorphous Unitarian God and believed instead in a vaguely Pantheistic “Over-Soul.” Emerson also rejected the idea of personal immortality.

On May 25, 209 years ago, American poet, essayist and moralist philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson was born (1803). After graduating Harvard in 1821, and teaching for a few years, Emerson was ordained into the Unitarian ministry. Six years later he resigned over doctrinal differences to form the group coming to be known as Transcendentalists, a company of writers and thinkers expressing an ethical idealism. The author of such well-known essays as “Self-Reliance,” “Circles,” “The Poet” and “Experience,” Emerson repudiated even the amorphous Unitarian God and believed instead in a vaguely Pantheistic “Over-Soul.” Emerson also rejected the idea of personal immortality.

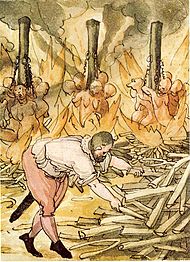

Today, Saturday, May 26, but 365 years ago, the first witch was hanged in America for the crime of witchcraft (1647). Alse Young was arrested, tried for this capital offense in Windsor, Connecticut, and hanged at Meeting House Square in Hartford, on what is now the site of the Old State House. There is no further record of Young’s trial or the specifics of the charge, only that Alse Young was a woman, as 80% of those executed for witchcraft were, and that her execution anticipated the 1692 Salem witch trials by some 45 years. There is no doubt that theologians reasoned, after the line from Leviticus, that “If the All-wise God punishes his creatures with tortures infinite in cruelty and duration, why should not his ministers, as far as they can, imitate him?” Consequently, torture was a favorite method, not for finding the truth of witchcraft, because witchcraft never contained any, but for quite effectively extracting confessions, because people will say anything to get the pain to stop. Witchcraft jurisprudence itself anticipated the anti-communist purges of the 1950s in the US: To confess to witchcraft was to earn a life sentence in jail; to deny the charge often resulted in a death sentence. The crime of witchcraft was not prosecuted in Connecticut after 1715, but the stain of execution for the imaginary crime of witchcraft remains.

Today, Saturday, May 26, but 365 years ago, the first witch was hanged in America for the crime of witchcraft (1647). Alse Young was arrested, tried for this capital offense in Windsor, Connecticut, and hanged at Meeting House Square in Hartford, on what is now the site of the Old State House. There is no further record of Young’s trial or the specifics of the charge, only that Alse Young was a woman, as 80% of those executed for witchcraft were, and that her execution anticipated the 1692 Salem witch trials by some 45 years. There is no doubt that theologians reasoned, after the line from Leviticus, that “If the All-wise God punishes his creatures with tortures infinite in cruelty and duration, why should not his ministers, as far as they can, imitate him?” Consequently, torture was a favorite method, not for finding the truth of witchcraft, because witchcraft never contained any, but for quite effectively extracting confessions, because people will say anything to get the pain to stop. Witchcraft jurisprudence itself anticipated the anti-communist purges of the 1950s in the US: To confess to witchcraft was to earn a life sentence in jail; to deny the charge often resulted in a death sentence. The crime of witchcraft was not prosecuted in Connecticut after 1715, but the stain of execution for the imaginary crime of witchcraft remains.

We can look back, but the Golden Age of Freethought is now. You can find full versions of these pages in Freethought history at the links in the excerpts above.