October 31: The Reformer Priest

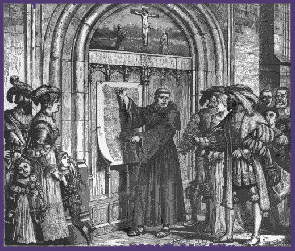

Martin Luther's Reformation (1517)

It was on this date, October 31, 1517, that the Protestant Reformation began in Germany, when 31-year-old Martin Luther posted his 95 theses at Wittenberg Cathedral. That document attacked papal abuses and the sale of offices and indulgences by church officials.

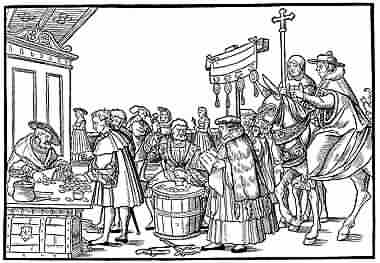

This wood engraving from the early 1500s depicts the sale of indulgences. The Pope's bull authorizing the sale hangs on a cross. (Jorg Breu the Elder)

Furthermore, Luther argued several other points:

• that Christian salvation could be achieved through faith alone – "justification by faith," as it was called – yet faith is a gift from God, not a matter of choice.

• a denial of the doctrine of Purgatory, which is mentioned nowhere in the Bible (the doctrine of the Trinity is also missing from the Bible, but that failed to trouble Luther).

• a denial of the Apostolic Succession, so that there is no intermediary between Man and God.

• an affirmation of the scriptures, and not the church hierarchy, as the final source for doctrine.

• an affirmation of the doctrine of Predestination, that those destined for heaven and for hell were chosen by God without regard for their deeds in life.

The pope who condemned Luther's heresy, Leo X,* was remarkably corrupt, as even the Catholic Encyclopedia gingerly admits: he enjoyed indecent comedies in the Vatican, lavish spending, gross nepotism, and buggering little boys. All Italy knew it, and all Europe begged for reform. But corruption was almost a tradition, reaching back centuries before Leo and enduring long afterward. Martin Luther was coarse, bigoted and superstitious, but he was far from wrong to argue for the reform of the lavish luxury and doctrinal defects of the Church at Rome.

* Luther's Popes (according to Joseph McCabe, The Popes and Their Church, 1918):

Julius II: had three known illegitimate children, and one of these, Felicia, he openly married at Rome while he was Pope. He promoted cardinals of his family. He was utterly unscrupulous in his diplomacy and his wars for the restoration of the Papal States. His temper was vile, and his language odoriferous. He maintained the colossal sale of offices and indulgences, though Europe was now in open revolt, and he made no serious effort to reform the cardinals. He was, the Venetian historian Bembi said, "a master of every type of cruelty," and Guicciardini himself says that if we call Julius "great" (as all Catholic literature now does), we are taking the word in a new sense. He was, soberly speaking, a vile type of man.

Leo X: had to face the revolt of Germany, where Luther was now in arms. But he believed that the Papacy would, as usual, stifle opposition, and he encouraged the licentious gaiety of Rome. The most indecent comedies were performed before him in the Vatican, and he was the worst nepotist in the series of Popes. He promoted to the cardinalate his friend Bibbiena — the writer of the worst of these indecent comedies, one of the most notoriously immoral clerics in Rome; also his illegitimate cousin, and his notoriously loose nephew and grandson of Innocent VIII, Innocenzo Cibo. He is accused of contracting unnatural vice after his election, and the contemporary suggestions of it are serious. In diplomacy his lying and duplicity are almost without parallel; and he had Cardinal Petrucci strangled in prison, and confiscated the property of other cardinals, on the ground that they conspired to kill him. He in eight years spent £10,000,000, largely in personal luxury and dissipation, which were mainly raised — while Luther stormed in Germany — by the corrupt sale of offices and indulgences.

Adrian VI and Clement VII: quiet and decent men, dazed by the revolt in Germany, but too weak to reform.

Paul III: the Farnese, who had won his promotion by his sister Giulia's liaison with Pope Alexander, and had had four children born in his own cardinalitial palace. As he was now seventy years old, his morals were, the Catholic will be pleased to hear, sound. But he made cardinals of his immoral nephews, and he protected the gay licence of the churchmen. Germany now spoke to Rome in stern accents, and Paul directed the few good cardinals to draft a scheme of reform. It remains "a scrap of paper" in the Vatican Archives to this day. Germany pressed for a Council, and he was compelled to yield, but he insisted that it must be held at Rome, under his presidency. Paul III resisted and obstructed with all his power the demand for reform. In 1540 he established the Society of Jesus, and before many years the black-robed sons of Ignatius were at work. Both they and the Pope began to plot for a war which should drown the new Protestantism in blood; but, luckily, the religious revolt now had its princes and armies. Paul was compelled to summon the Council of Trent (1546), which was supposed to be a common gathering of Papalists and Reformers, to define doctrine and reform the Church "in head and members." From Paul's instructions to his Legates we see that to the end he resisted reform, and merely sought to define doctrine, so as to have a standard for the condemnation and extinction of "the heretics." He died in 1549, the last of the long series of Unholy Fathers.

Originally published October 2003 by Ronald Bruce Meyer.