September 26: Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh (1833)

It was on this date, September 26, 1833, that Charles Bradlaugh was born in Hoxton, London. At the age of twelve his father's employer hired him on as an office boy. But Bradlaugh began reading the writings of Richard Carlile, who had been imprisoned under English law for blasphemy and seditious libel in 1819. Bradlaugh afterward began to question the truth of Christianity. This led to arguments with his father, so Bradlaugh left home in 1849, at age 16.

He briefly enlisted, but army life in Ireland was disagreeable to him, so he won a discharge in 1853 and again found work in a law office. Seven years later, in 1860, he joined Joseph Barker, a former Chartist, and established the radical journal, The National Reformer. In 1866 Bradlaugh helped to establish the National Secular Society, and soon became friends with feminist and reformer Annie Besant, who worked at the journal alongside Bradlaugh.

It was in 1877 that Bradlaugh and Besant re-published Charles Knowlton's book advocating birth control, The Fruits of Philosophy. Both were charged with publishing material that was "likely to deprave or corrupt those whose minds are open to immoral influences," found guilty and sentenced to six months in prison. In court they argued that "we think it more moral to prevent conception of children than, after they are born, to murder them by want of food, air and clothing." An appeal quashed the verdict.

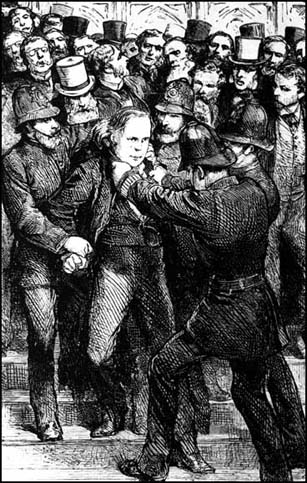

Bradlaugh was elected to Parliament in 1880, but as he was not a Christian, he asked for permission to affirm rather swear the oath of office. Even with Prime Minister William Gladstone's support, the Speaker refused. The MPs ratified the Speaker's decision. When he attempted to take his seat, anyway, the Sergeant-at-Arms arrested him. Bradlaugh was ejected and refused affirmation several times.

Playwright George Bernard Shaw supported his right to be seated, as did MP John Stuart Mill, who suffered for it, politically. Although the Conservative party opposed him, their leader, Benjamin Disraeli, suggested Bradlaugh may become a martyr if Parliament persisted in its persecution. Both the Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Catholic Cardinal Manning, argued against the right of atheists to be MPs.

In Humanity's Gain from Unbelief (1889), Bradlaugh argued against the necessity for belief:

A ground frequently taken by Christian theologians is that the progress and civilization of the world are due to Christianity... My allegation will be that the special services rendered to human progress by these exceptional men have not been in consequence of their adhesion to Christianity, but in spite of it, and that the specific points of advantage to human kind have been in ratio of their direct opposition to precise Biblical enactments.

A new Speaker allowed Bradlaugh to affirm the oath of office in 1886, and he was finally seated in the House of Commons. Still an Atheist, Charles Bradlaugh died on 30 January 1891 at age 57. His funeral was attended by 3,000 mourners and he specified that "my body be buried as cheaply as possible and no speeches be permitted at my funeral," a wish his daughter, Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner, respected. So many people from all classes came to pay their respects, that a special train was routed from Waterloo to his family burial place in Brookwood. Among the mourners was a young Indian student named Gandhi.

It was Bradlaugh, in his 1864 Plea for Atheism, who said,

The atheist does not say, "There is no God," but he says "I know not what you mean by God; the word is to me a sound conveying no clear or distinct affirmation." ... Atheism, properly understood, is no mere disbelief; is in no wise a cold, barren negative; it is, on the contrary, a hearty, fruitful affirmation of all truth, and involves the positive assertion of action of highest humanity.

Originally published September 2003 by Ronald Bruce Meyer.