September 13: The Religious Tolerance of Roger Williams

Roger Williams Banished (1635):

Separation of Church and State

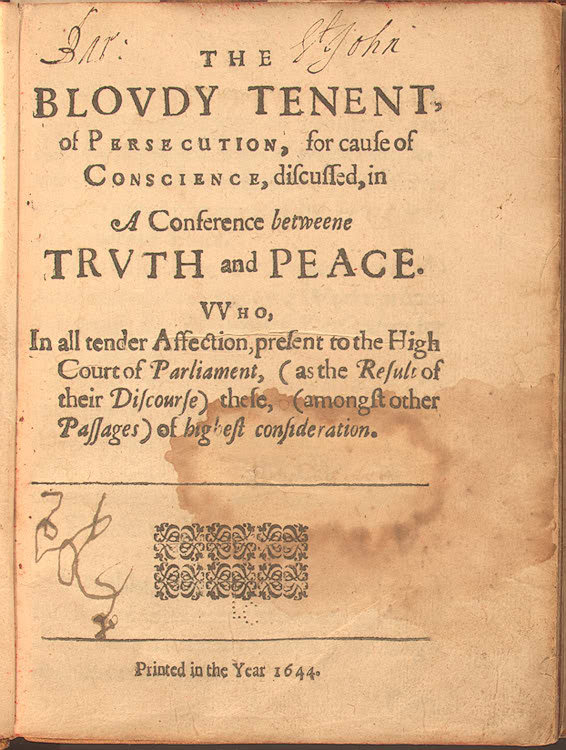

Roger Williams published his defense of separation of religion from government in London: "The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution, for Cause of Conscience" (1644). The book was a dialog between Truth and Peace.

It was on this date, September 13, 1635, that Separatist preacher Roger Williams, aged about 32, was banished by the Massachusetts General Court for perpetually advocating religious tolerance and separation of church and state.[1] For denouncing the Massachusetts Bay Company charter, and for holding "divers new and dangerous opinions against the authority of magistrates and ... yet maintaineth the same without retraction,"[2] he was sentenced by a religious authority for a civil crime.

Roger Williams was not the first separationist. A Renaissance Italian cleric, who died about the year Williams was born, Fausto Sozinni, better known as Faustus Socinus (1539-1604), first advocated separation between the secular and the clerical. But he did so in books published anonymously, and thereafter removing himself to Poland, where he might enjoy a longer life with his beliefs. England had never allowed the Inquisition to operate on its soil, but was not to abandon the belief that heretics must be executed (De haeretico comburendo) until 1678.

Religious toleration does not come easily to those who dispense God's will – "error hath not the same right as truth," the Catholics would say – but the Socinians probably influenced the writings of John Locke and Thomas Jefferson. Roger Williams's attraction to Puritanism, and England's intolerance of that branch of the Protestant tree, persuaded him to leave for the New World. He landed at Plymouth in 1631 and became an "elder" in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

But this bright young preacher taught "that no person should be restrained from, nor constrained to, any worship or ministry," except in accordance with the dictates of his own conscience.[3] To Roger Williams, that did not give the Massachusetts Bay Colony the prerogative to steal Indian lands, deny the vote to the unsaved, or to prosecute civil crimes under religious statutes; in other words, "That the civil magistrate's power extends only to the bodies and goods, and outward state of men..." As Williams wrote in his 1644 publication, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution, for Cause of Conscience, "God requireth not an uniformity of Religion to be inacted and inforced in any civill state... true civility and Christianity may both flourish in a state or Kingdome, notwithstanding the permission of divers and contrary consciences, either of Jew or Gentile."[4]

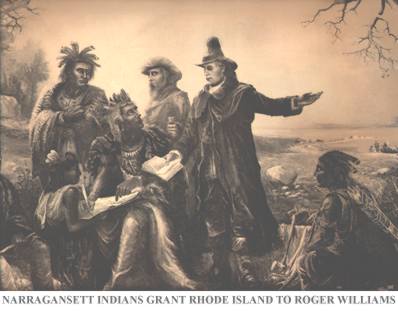

In this, Williams both anticipated and exceeded the toleration enacted later in Maryland, whose Catholic minority quickly passed laws of toleration only for those believing in Jesus Christ, that is, the Protestant majority, but not for Jews, Quakers, Deists and (of course) Freethinkers. In June 1636, Williams purchased land from the Narragansett tribe to found a haven for dissenters "to hold forth liberty of conscience."[5] Anne Hutchinson, America's first major female religious leader, arrived there from Massachusetts in 1638, after being excommunicated and banished. It appeared that Massachusetts Bay magistrates regarded Rhode Island as a convenient place to park their problem children. In 1644, Williams obtained a royal charter for the colony of Rhode Island, which quickly gained a reputation for toleration of religious diversity under his guidance.

Roger Williams purchased his colony from the natives, then made all welcome – even those whose religious opinions might be considered dangerous. Unlike the tolerant Williams, Massachusetts Bay colony sought to break "the very neck of Schism and vile opinions."

To his credit, although Williams first called himself a Baptist, he later described himself as a "seeker," that is, a nondenominational Christian seeking spiritual truth, which is about as close to Unitarianism as one could come. And Roger Williams was the first to use the term later adopted by Thomas Jefferson in his letter to the Danbury Baptists: "wall of separation." Like Jefferson, Williams argued that such a separation benefited religion as well as government:

When they [the Church] have opened a gap in the hedge or wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world, God hath ever broke down the wall itself, removed the Candlestick, etc., and made His Garden a wilderness as it is this day. And that therefore if He will ever please to restore His garden and Paradise again, it must of necessity be walled in peculiarly unto Himself from the world, and all that be saved out of the world are to be transplanted out of the wilderness of the World.[6]

Roger Williams died at Providence between 16 January and 16 April 1683, still believing that good walls make good neighbors.

[1] The date is not entirely clear from the sources. The date of 13 September 1635 is sourced on William D. Blake. Almanac of the Christian Church, Minneapolis: Bethany House, 1987. However, the Dictionary of American Biography, which cites original documentation (see below), says it was 9 October 1635. So do Edwin S. Gaustad (Liberty of Conscience: Roger Williams in America in Theodore P. Greene, Roger Williams and the Massachusetts Magistrates, Boston: Heath, 1964), Samuel H. Brockunier (in Greene), and several Web sources, including Wikipedia). Edmund S. Morgan (Roger Williams: the Church and the State in Greene), rather unhelpfully says it was "early October." Romeo Elton (Life of Roger Williams, the Earliest Legislator and True Champion for a Full and Absolute Liberty of Conscience, Providence: G.H. Whitney, 1853) says it was 3 November 1635. At last, I checked the microfilm version of Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay (Boston: W. White, 1853-54, vol. 1, pp. 160-161), on which the Dictionary of American Biography presumably based its date. But I found a marginal notation indicating, if I read type correctly, that the magistrates pronounced Williams's banishment on 3 September 1635! I've settled on the first date I found (13 September), and I would be delighted to learn that that is correct – taking into account the calendar adjustment of 1582, from Julian to Gregorian – but of course I'd rather be right.

[2] Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, as quoted in a sermon, "The Value of Baptist Principles to the American Government," read before the National Baptist Convention, Atlanta, Ga., 1895 and the Baptist Ministers' Conference, Washington, D.C., 1897; found on the Library of Congress Web site.

[3] Amasa Mason Eaton, Roger Williams, the Founder of Providence – the Pioneer of Religious Liberty, Providence: E.L. Freeman, 1908 (microfilm).

[4] Roger Williams, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution, for Cause of Conscience, in a Conference Between Truth and Peace, London, 1644.

[5] From a 1640 agreement signed at Providence, quoted on the Wikipedia) Web site.

[6] "Mr. Cotton's Letter Lately Printed, Examined and Answered," in The Complete Writings of Roger Williams, Volume 1, page 108, 1644.

Originally published September 2003 by Ronald Bruce Meyer.