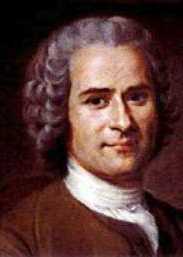

June 28: Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712)

It was on this date, June 28, 1712, that Swiss-born French writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva, which at the time was a Calvinist city. His mother died shortly after his birth, and his Huguenot father abandoned him when he was 10. Rousseau lived with relatives until age 16, then sought his fortune in France.

While in Paris, he associated with Denis Diderot, who introduced him to Jean d'Alembert, Baron d'Holbach, Madame d'Epinay and the other resident Rationalists and Encyclopædists, includingVoltaire.

He took up with Madame de Warens (d. 1762), and, in exchange for her financial support, converted to Roman Catholicism. From 1731 until 1740, while engaging in his own education, Rousseau was the widow's live-in lover. After losing her, Rousseau took up with an uneducated seamstress, Thérèse Lavasseur, who bore him five children, all of whom were abandoned to foundling homes. Thérèse stayed with Rousseau the rest of his life.

In 1750 Rousseau won an essay contest and embarked on a career of writing for social reform. In 1755 he published A Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, in which he put forth his idea of the "noble savage," the inspiration for Edgar Rice Burroughs to create his immortal Tarzan character. Rousseau developed the idea that people in the "state of nature" are basically good and that they become corrupted by society.

At age 50, he used this idea in his most notable work, Du Contrat Social (On the Social Contract, 1762). In it he argues that society is a contract between the sovereign and the people, and that people give up liberty in exchange for protection: "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains," Rousseau writes. As with the "state of nature," the "social contract" has to be accepted as poetic license — no one has yet shown that there ever was some kind of Golden Age from which we are now fallen, or produced a signed copy of a Social Contract!

In Émile (1762), which urges educational reform, Rousseau demonstrated that he was a Deist, saying,

The Supreme Being is best displayed by the fixed and unalterable order of nature. If there should happen many exceptions to such general laws, I should no longer know what to think; and for my part, I must confess I believe too much in God to believe in so many miracles so little worthy of him. (¶149)

Elsewhere, Rousseau discounts the Christian notion of hell:

It would be to as little purpose to ask me whether the torments of the wicked will be eternal. ... If supreme justice avenges itself on the wicked, it avenges itself on them here below. (¶¶81-82)

His ideas on religion in Émile led to church-inspired book burnings and Rousseau's eventual expulsion from Paris. He returned to Geneva, the city of his birth, but was expelled for "irreligion," and his citizenship was revoked. He accepted the hospitality of David Hume in England, but his chronic paranoia impelled a falling out with his host and he returned to France.

By 1770 Rousseau had won permission to return to Paris. He moved to a suburb in 1778 and died there of apoplexy on July 2, a month after Voltaire had died. His contributions to social and educational reform were sincere, but his mental imbalance and defective character hobbled his work for humanity. His Romantic regard for "pure Christianity," along with his pleading for religion sanctified by sentiment, sets Rousseau apart from his more skeptical colleagues.

Originally published June 2003 by Ronald Bruce Meyer.