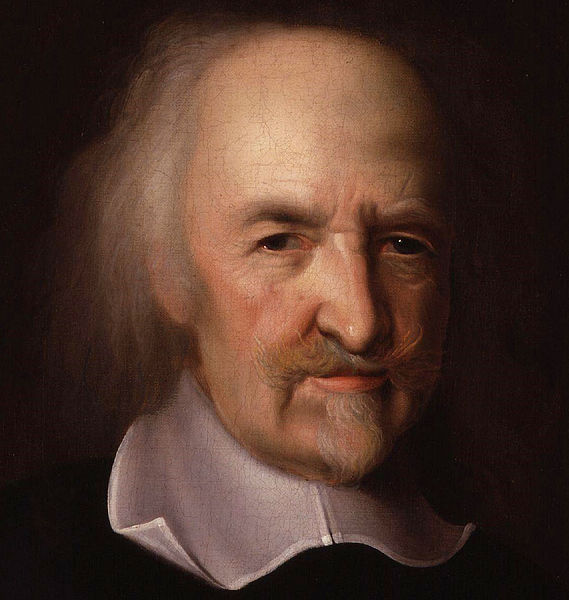

April 5: Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes (1588)

It was on this date, April 5, 1588 that English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes was born. He grew up in an impoverished clerical family in Malmesbury, Wiltshire, England, and was classically educated at Oxford. On the Continent, he got to know such intellectuals as Descartes and Galileo. Caught up in the turmoil preceding the English Civil War, he fled to France in 1640, where he remained until 1651.

It was in 1651 that Hobbes saw the publication in London of his greatest work, Leviathan. In it, Hobbes concludes that the natural condition of humanity is a state of perpetual war of all against all. The social contract with the sovereign, therefore, was a kind of protection racket. The alternative, he wrote, was a condition in which "there is no place for industry, ... no knowledge of the face of the earth, no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death; and the life of people, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short."

Leviathan was named for the immense power of the sovereign, and in it he wrote of religion,

[T]he acknowledging of one God, eternal, infinite, and omnipotent, may more easily be derived, from the desire men have to know the causes of natural bodies and their several virtues and operations, than from the fear of what was to befall them in time to come. For he that from any effect he seeth come to pass should reason to the next and immediate cause thereof, and from thence to the cause of that cause, and plunge himself profoundly in the pursuit of causes, shall at last come to this, that there must be, as even the heathen philosophers confessed, one first mover, that is, a first and an eternal cause of all things, which is that which men mean by the name of God, and all this without thought of their fortune; the solicitude whereof both inclines to fear and hinders them from the search of the causes of other things, and thereby gives occasion of feigning of as many gods as there be men that feign them.

A bill designed to punish blasphemous literature passed the House of Commons in January 1667, and Leviathan was one of two books specifically targeted. Though the bill never became law, it had the desired effect on Hobbes, who is said to have become more regular at church. Because of his writings, especially Leviathan, Hobbes lived in serious danger of prosecution after the restoration of Charles II.

Hobbes never denied the existence of God, but he opposed any positive revealed religion, including Christianity, and most likely did not believe in an afterlife. Hobbes maintained, perhaps to duck the charges of heresy, that the sovereign was the best interpreter of God's will. He was neither the first nor the last freethinker to hide the light of skepticism under the bushel of belief. This caution probably allowed Thomas Hobbes to live past 90 years, in an era when most Europeans died at half that age.

Born in the year of the Spanish Armada (1588), Thomas Hobbes died at Hardwick on 4 December 1679.

Originally published April 2003 by Ronald Bruce Meyer.