February 3: The Four Chaplains and God’s Love

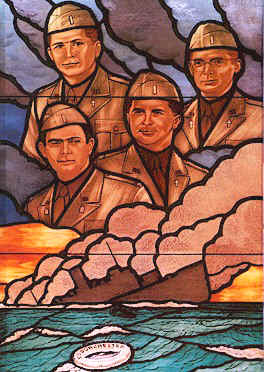

Four Chaplains (1943)

It was on this date, February 3, 1943, that four chaplains aboard the US Army Transport Dorchester, sinking from a German U-Boat attack in the icy North Atlantic, helped other soldiers board lifeboats and gave up their own life jackets when the supply ran out, thereby sacrificing their lives to save the lives of sailors and soldiers abandoning a sinking ship.

The heroism and sacrifice of the Four Chaplains were officially celebrated by the US Congress with a Purple Heart and Distinguished Service Cross for each (December 19, 1944) and an act of Congress designating February 3 as “Four Chaplains Day”; a “Four Chaplains Medal” (July 14, 1960), a United States Postal Service stamp (issued May 28, 1948), and a “Chapel of the Four Chaplains” inside Grace Baptist church in Philadelphia, dedicated by Pres. Harry Truman (February 3, 1951). Congress wanted to confer the Medal of Honor, but that award requires heroism performed under fire.

The “Four Chaplains” were also celebrated by the American Legion, by the “Heroes Chapel Window” of stained glass at the National Cathedral, in Washington, D.C., and by numerous other private religious and social groups – as well as in newspaper articles, books and films.

The story of the “Four Chaplains” was already approaching legendary proportions within a few years of their deaths. And, for such a gripping story, why not?

The “Four Chaplains” – Clark Poling of the Dutch Reformed Protestant church, George Lansing Fox of the Methodist Protestant church, John Washington of the Roman Catholic church and Alexander David Goode, a Jewish rabbi – were assigned to the USAT Dorchester, a merchant vessel (formerly SS Dorchester) converted to an armored troop transport. The Dorchester left New York, in a convoy with other transports carrying World War II troops and supplies, bound for an Army base in Greenland, on January 23, 1943. Their route took them through waters known to be patrolled by German submarines, called as U-boats, whose most effective weapon is the torpedo, an underwater self-propelled missile that can strike almost without warning.

On the morning of 3 February 1943, one of three torpedoes fired by the U-boat U-223 hit the midsection of the Dorchester, knocking out the ship’s electrical system and causing it to founder within 30 minutes. In that time, the below-decks troops had to grab life jackets, get up on deck and find space in life boats in the sub-freezing air, then get away from the Dorchester before it disappeared into the freezing water. In those pre-dawn Arctic hours, the escape was complicated by the dark and the failure of the ship’s lights.

The heroism of the “Four Chaplains” resided in their calm amid the panic, during which they guided frightened soldiers to lifeboat stations, distributed life jackets and helped others over the side to the lifeboats. “Survivors remembered hearing their comforting voices raised in prayer,” said one account. “Others remember them handing life jackets to man after man and, at the end, giving up their own.”

In fact, the sinking of the Dorchester, in which the Four Chaplains and 670 other men died, if it proves anything, proves that nothing fails like prayer. You see, if the actions of the “Four Chaplains” was a great moral lesson in selflessness for the survivors to witness, it must be admitted that it was a hard lesson on those who perished.

That God had to drown 674 US soldiers in icy water to give us this heart-warming story, proves not the love of Jehovah, but his malevolence. God could not protect the Four Chaplains, or the sailors who died. God could not even prevent the German U-boat from torpedoing the Dorchester.

Until that day, these four “religious” heroes did nothing practically useful for America, except to die in place of, perhaps, four sailors, on a doomed ship. The “Four Chaplains” did what any human being of decency and upright character would do for a fellow human being, religion or no. And that’s just the point: there was no God in their gallantry, no Jesus in their generosity, and in their courage no creed.

Originally published January 2011 by Ronald Bruce Meyer.