December 24: Matthew Arnold and his “Sea of Faith”

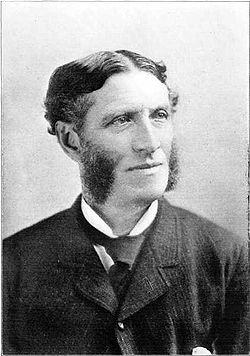

Matthew Arnold (1822)

It was on this date, December 24, 1822, that British critic and poet Matthew Arnold was born at Laleham on the Thames, the son of the headmaster at Rugby. Arnold was educated at Winchester, Rugby, and Balliol College, Oxford. At Rugby and Oxford he won prizes for his poetry. In 1847 Arnold became private secretary to Lord Lansdowne. In 1851 Arnold became inspector of schools, which assured him an income but occupied so much of his energy that we can judge his talent only on relatively few poems.

Of his private life little is known, but he was influenced by George Sand and admired French culture, Goethe and Milton. A snappy dresser and a raconteur, Arnold was generally sunny in disposition and sentimental in his poetry. Arnold was a leading literary critic and wrote many essays, which displayed a seriously Rationalist streak. On religion, he attempted to reconcile tradition with the results of then-new Higher Criticism, concluding along with Wordsworth that God is a "Stream of Tendency."

Arnold's poem "Dover Beach," written in 1851, seems to lament the loss of faith in a post-Enlightenment world:

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth's shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furl'd.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarums of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

It is a Romantic, even a Victorian, notion that faith provides beauty, joy, love, light, certitude, peace and help for pain. But in fact and in history, religious faith, the "Sea of Faith," was less "a bright girdle furl'd" "round earth's shore" and more like a straitjacket. If we really are to compare, we must look at facts, not poetry.

Beauty? Four-fifths of Christendom lived in squalor in the Middle Ages (450-1550), without sanitation, without bathing, and without any idea that filth and food should be kept apart. Joy? The average age at death was 35 during the Middle Ages — it is more than double that today. Women could count on burying half their children in infancy, when they did not themselves die of post-partum infection.

Love? You see no maternal affection in paintings from the Middle Ages. Children died so often and so young, it wasn't worth it to get too attached.

Light? Ninety-five to 99% of the populace, including kings, lords, priests and monks, were illiterate. Certitude? Granted, the Church was the final authority. Too bad everything about which the church was certain has turned out to be wrong. Science, a human invention, has shown the way to discovering how nature operates.

Peace? The Middle Ages featured the bloodiest wars and the most brutal persecutions for opinion that the world had ever seen. Far from peaceful, the Sea of Faith spilled oceans of blood.

Help for pain? If you got sick in the Middle Ages, you would have to wait until the 18th century to find hospitals. For centuries the churches would not allow dissection and stymied development of anesthesia, especially for birthing women — Eve's curse, you know. No holy book gave us the germ theory of disease. That was the discovery of an apostate scientist.

In other poems, such as "Immortality" and "Requiescat," and in other writings — such as Culture and Anarchy (1869) and Literature and Dogma (1873) — it is clear that Arnold denied belief in immortality and a personal God. He defined the only God he recognized as "a Power, not ourselves. which makes for righteousness," and religion as "morality touched with emotion." In the preface of God and the Bible in 1875, Arnold wrote, “The personages of the Christian heaven and their conversations are no more matter of fact than the personages of the Greek Olympus and their conversations.”

An admirer of American poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, Arnold toured the United States delivering lectures on education, democracy and Emerson. He died of heart failure on 15 April 1888, two years after he retired from his government job, while running to meet his daughter at a train station. He was buried at All Saints Churchyard, Laleham, Middlesex, England. It was Matthew Arnold who said, "The freethinking of one age is the common sense of the next."

NB:You can find the complete text of the three Matthew Arnold poems referenced above, and others, at this link.

Originally published December 2003.