November 4: Egyptian Religion Revealed

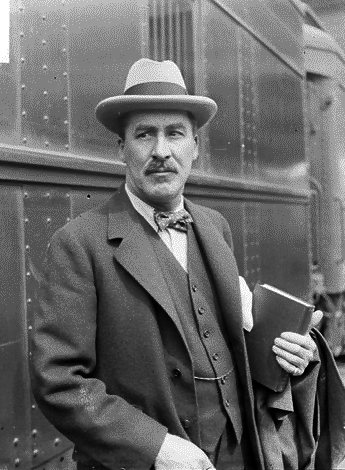

Howard Carter and the Ancient Egyptians (1922)

It was on this date, November 4, 1922, that English archaeologist Howard Carter found Egyptian King Tutankhamen's tomb. As Carter wrote,

At about 10am I discovered beneath almost the first hut attached the first traces of the entrance of the tomb (Tut.ankh.amen). ... And, that it was of the nature of a sunken staircase entrance to a tomb of the type of the XVIIIth Dyn. ...

The tomb yielded a wealth of artifacts and knowledge. What we know about Ancient Egypt today suggests that the assumptions before Carter, and before the translations of the inscriptions and papyri by Champollion were religiously inspired fabrications.

The soberly religious and severe Egyptians were in fact as cheerful and fun-loving as any Western society today. The kings affected solemnity as befits their pose as divine rulers, but tomb inscriptions and texts such as the Book of the Dead show that by 3000 BCE the Egyptians possessed a moral code far superior to the Ten Commandments and the raving Hebrew prophets. These give the lie to the Christian claim that the children of Israel taught the world pure religion and monotheism, or that the pagan world stumbled in darkness until the light of Christ shone on it.

We see not only love poetry and popular stories, but children's toys, paintings of daily life, and humanitarian moral treatises such as the Prisse Papyrus. There was almost certainly some borrowing — by the Hebrews from the Egyptians: the Song of Solomon in the Bible bears the remains of Egyptian wedding songs, and the Potiphar's wife story (Genesis 39:1-23), was taken from the Egyptian Tale of Two Brothers.

The claim that the Ancient Egyptians were exceptionally religious and moral, based on their belief in immortality, is easily discarded. Until about 1400 BCE Egyptian priests taught that only kings and nobles were immortal. Even writings such as The Maxims of Ptah-hotep (Prisse Papyrus), when they refer to a god or gods (neter or neteru) do so in a humanist sense. Many make no reference to God whatsoever, and one even exclaims, "If I knew where God is I would certainly make an offering to him."

The reign of Amenhotep III is generally considered Egypt's Golden Age, yet historians Adolf Erman and James Henry Breasted call it an age of heresy. The famous Egyptologist E.A.W. Budge says that "a God more or less made no difference to Amenhotep III," and that "he was as willing to worship himself as Amen." The Song of the Harper, possibly written about the time of Amenhotep's son, the religious reformer Ikhnaten, can be summarized by the modern maxim, "Let us eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die." Like their Christian successors, the Egyptian priests tried to suppress this wedding song because of its "atheistic joy in life," but the Egyptians remained cheerfully defiant.

* Prisse d'Avennes was the French Egyptologist who discovered the papyrus, which is today known by his name. The Prisse Papyrus, written before 2000 BCE, is a copy of a work written by Ptah-Hotep, Grand Vizier under the Fifth Dynasty King Djedkare Isesi (Tankeris). He called it The Instructions (or Maxims) of Ptah-Hotep.

Originally published October 2003 by Ronald Bruce Meyer.