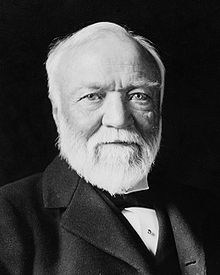

November 25: Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (1835)

It was on this date, November 25, 1835, that industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland. Hard times in Scotland forced his family to emigrate to the US in 1848. Andrew naturally entered the textile industry as a bobbin boy in a cotton mill near Allegheny, Pennsylvania. He quickly graduated to the railroad business and developed such an expertise that President Lincoln called on the otherwise scantily educated Carnegie for advice on transporting troops by rail. By the close of the American Civil War, Carnegie had organized the Carnegie Steel Company, which brought the industry to Pittsburgh.

By age sixty-five, Carnegie had acquired a great fortune — he was considered the richest man in the country — and sold his steel company to J.P. Morgan for $480 million. Thereafter he devoted his life to philanthropy, although he rejected the label, saying instead that he was "a distributor of wealth for the improvement of mankind." By the time he died, Carnegie had given away over $350,000,000, a fortune substantially greater in today's dollars.

Carnegie considered philanthropy a moral imperative, and he was one of the first philanthropists to speak in those terms publicly. "The man who dies rich dies disgraced," he said. And, as he wrote in The Gospel of Wealth (1889),

This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of wealth: first, to set an example of modest unostentatious living, shunning display; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; and, after doing so, to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds which he is strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial results for the community.

Believing that "only in popular education can man erect the structure of an enduring civilization," the Carnegie Corporation of New York[1] was created in 1911 to promote "the advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding." With his goal being "to do real and permanent good in this world," Carnegie not only supported international peace and security, international development, and the strengthening of US democracy, but founded hundreds of libraries and cultural institutions and gave away millions in grants. What may have seemed like "Christian charity" was decidedly nothing of the kind.

Biographer B.J. Hendrick shows that Carnegie was a skeptic from a young age. Once his mother, returning from church, said to Andrew, "You would have enjoyed the sermon today, Andrew; there wasn't a word of religion in it."[2] In Carnegie's own writings he avoided religion as far as possible. But in his Life of James Watt (1905) he speaks of "the mysterious realm which envelopes man" and later makes the Agnostic statement that "we are but young in all this mystery business."[3]

In fact, American author and liberal cleric Moncure Daniel Conway, who knew Carnegie well, says that he always described himself as an Agnostic. Before he died in Lenox, Massachusetts, on 11 August 1919, he made a confession of faith printed in the Truthseeker magazine (August 23, 1919). In it, Carnegie said he abjured "all creeds" and that he was "a disciple of Confucius and Franklin."[4] A Catholic weekly stated that when Carnegie was challenged about his many gifts of church organs he humorously replied that he did this "in the hope that the organ music would distract the congregation's attention from the rest of the service."[5]

[1] The Carnegie Corporation can be contacted through its website. In case you were wondering, the last name is stressed on the second syllable: (car NEG ee). [2] Burton Jesse Hendrick, Life of Andrew Carnegie, 2 vol., 1932, repr. 1989. [3] Andrew Carnegie, The Life of James Watt, 1905, pp. 33, 54. [4] Quoted in Joseph McCabe, "Andrew Carnegie" in A Rationalist Encyclopedia: A Book of Reference on Religion, Philosophy, Ethics, and Science, 1948, repr. 1971. [5] Ira D. Cardiff, What Great Men Think of Religion, 1945, repr. 1972. Cardiff reproduces other quotes attributed to Carnegie which may or may not be authentic for the normally reticent industrialist: "I don't believe in God. My God is patriotism. Teach a man to be a good citizen and you have solved the problem of life." -…- "I have not bothered Providence with my petitions for about forty years." -…- "I will give a million dollars for any convincing proof of a future life."

Originally published November 2003.